As we head into 2021, there is a large consensus that the massive monetary interventions in 2020 will lead to an explosion of economic growth, inflation, and higher interest rates. We suspect that the outcome of more debt-driven spending will lead to a disappointment in growth and disinflation instead.

Milton Friedman once said:

“Inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon, in the sense that it cannot occur without a more rapid increase in the quantity of money than in output.”

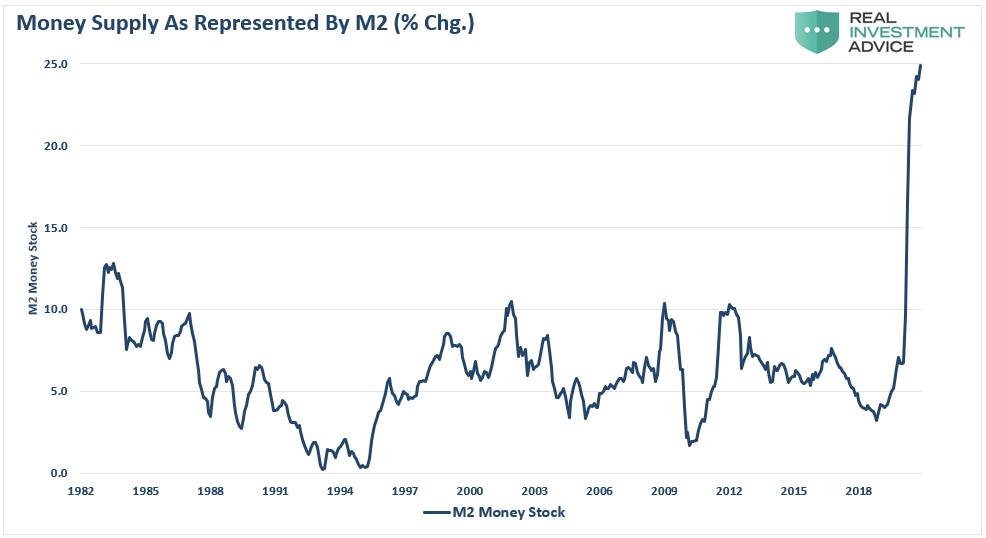

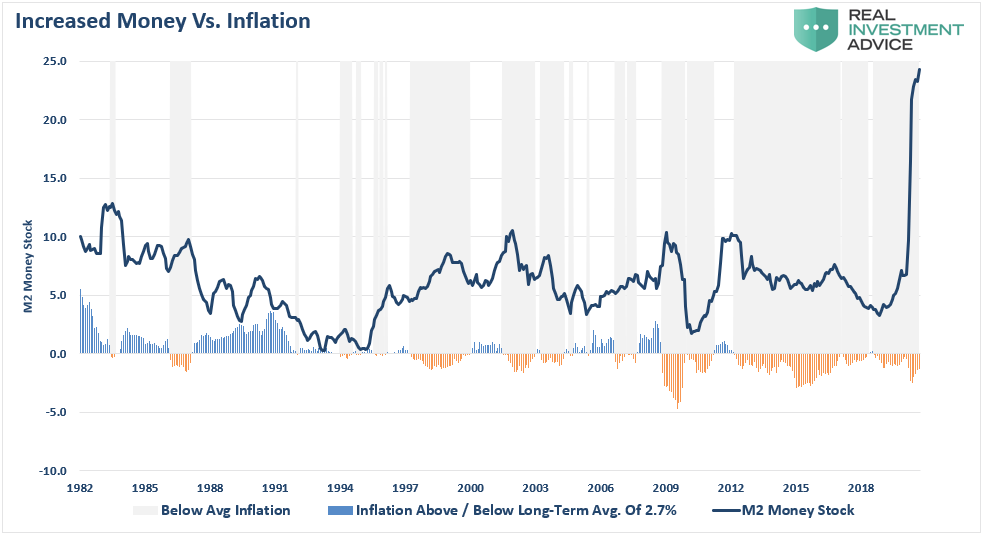

There is little argument currently that the Federal Reserve is “printing money” without any reservation. The chart below is the “supply of money” as represented by M2.

That massive spike in M2 is from the Government’s gigantic monetary rescue to combat the pandemic-related economic shutdown.

“In our analysis, the ‘end game’ for the Fed’s twin asset bubbles in stocks and bonds is inflation.” – Crescat Capital

Of course, if the massive monetary infusions create an economic boom, then a surge in inflation and interest rates should follow. As noted recently by GaveKal:

“In summary, my indicators tell me that US growth will be strong and we are on the right side of the four quadrants framework. As prices seem set to accelerate, we are moving into the upper half, which means that 2021 should see an inflationary boom in the US.”

There are several reasons why expectations may fall short of reality.

Why Printing Money Won’t Create Inflation

For the last 12-years, the annual refrain from economists has been “this year is the year of economic growth and inflation.” Each year has been a disappointment of those expectations.

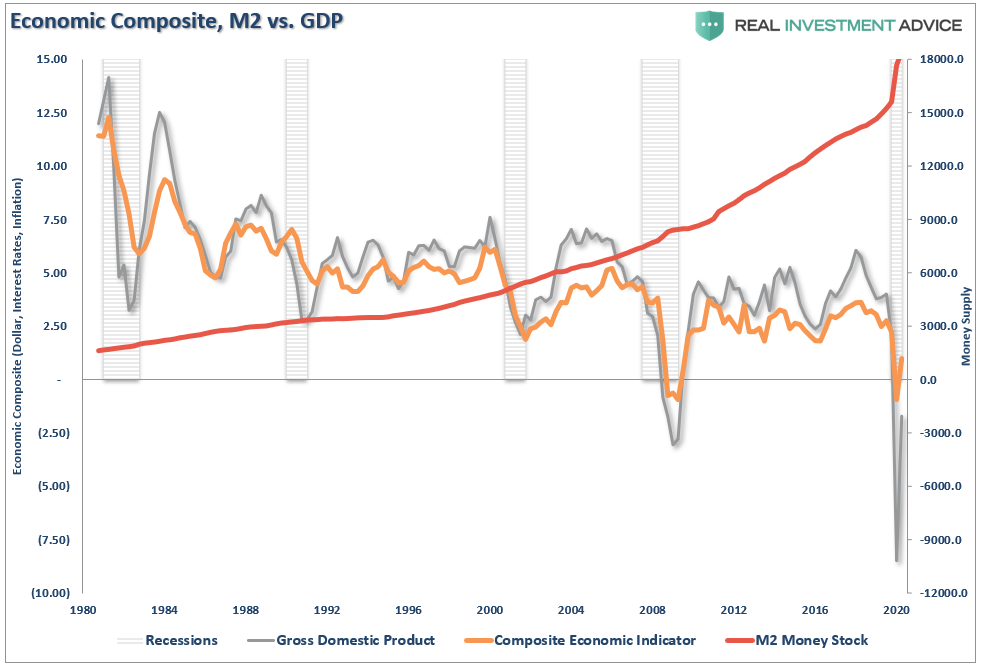

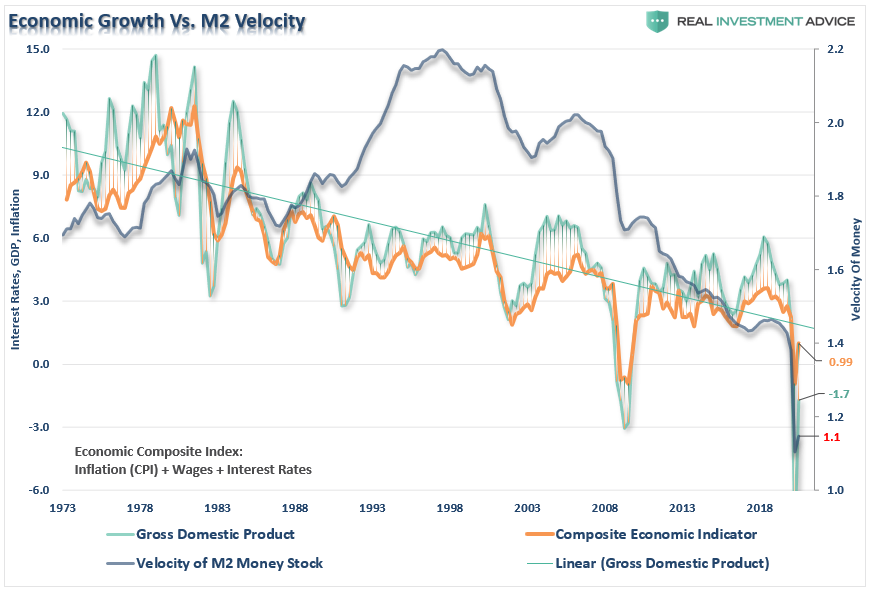

The chart below compares the money supply to GDP growth and our composite economic indicator. The composite includes inflation, wages, and interest rates, which directly correlate to economic activity.

While in theory, “printing money” should lead to an increase in economic activity and inflation, such has not been the case.

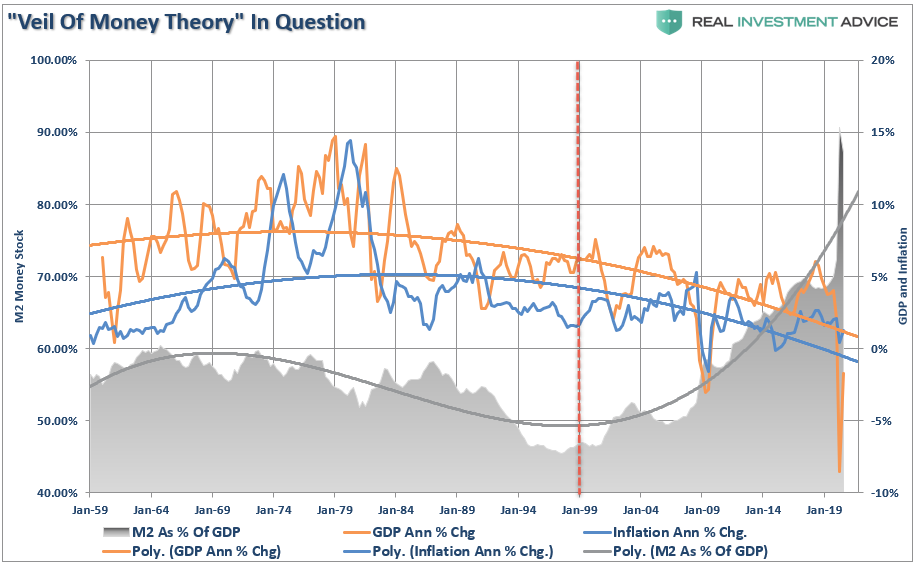

A better way to look at this is through the “veil of money” theory. If money is a commodity, more of it should lead to less purchasing power, resulting in inflation. However, this theory began to fail as Governments attempted to adjust interest rates rather than maintain a gold standard.

As shown, beginning in 2000, the “money supply” as a percentage of GDP has exploded higher without a resulting rise in inflation or economic growth. As shown by the attendant trendlines, it has been quite the opposite.

However, this is where monetary velocity becomes essential.

Monetary Velocity

The Federal Reserve has failed to grasp that monetary policy is “deflationary” when “debt” is required to fund it.

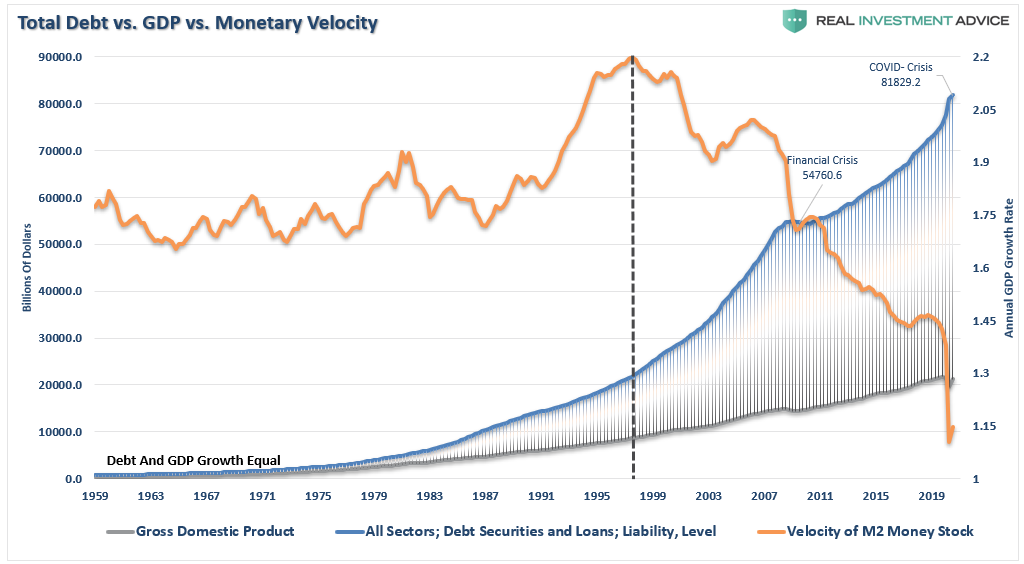

How do we know this? Monetary velocity tells the story.

What is “monetary velocity?”

“The velocity of money is important for measuring the rate at which money in circulation is used for purchasing goods and services. Velocity is useful in gauging the health and vitality of the economy. High money velocity is usually associated with a healthy, expanding economy. Low money velocity is usually associated with recessions and contractions.” – Investopedia

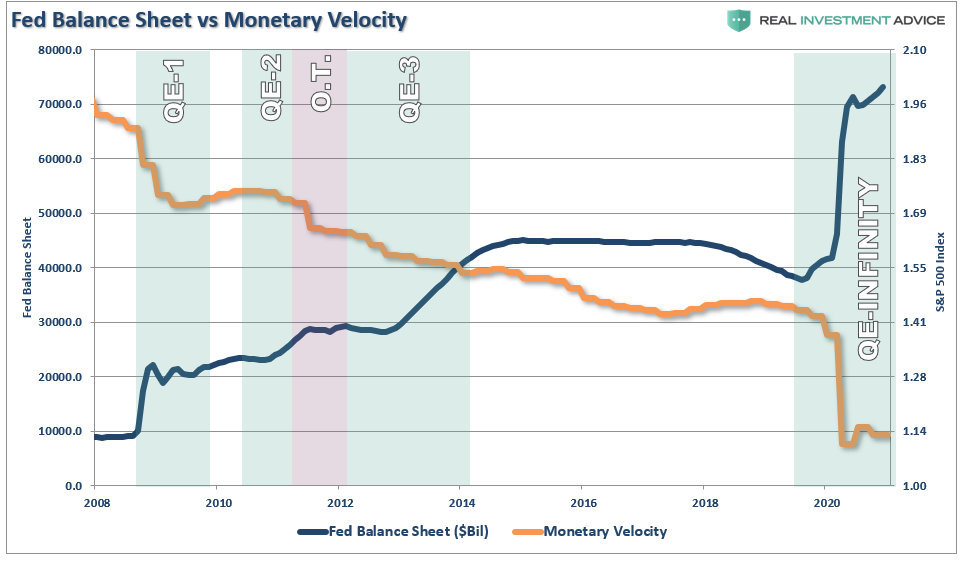

With each monetary policy intervention, the velocity of money has slowed along with the breadth and strength of economic activity.

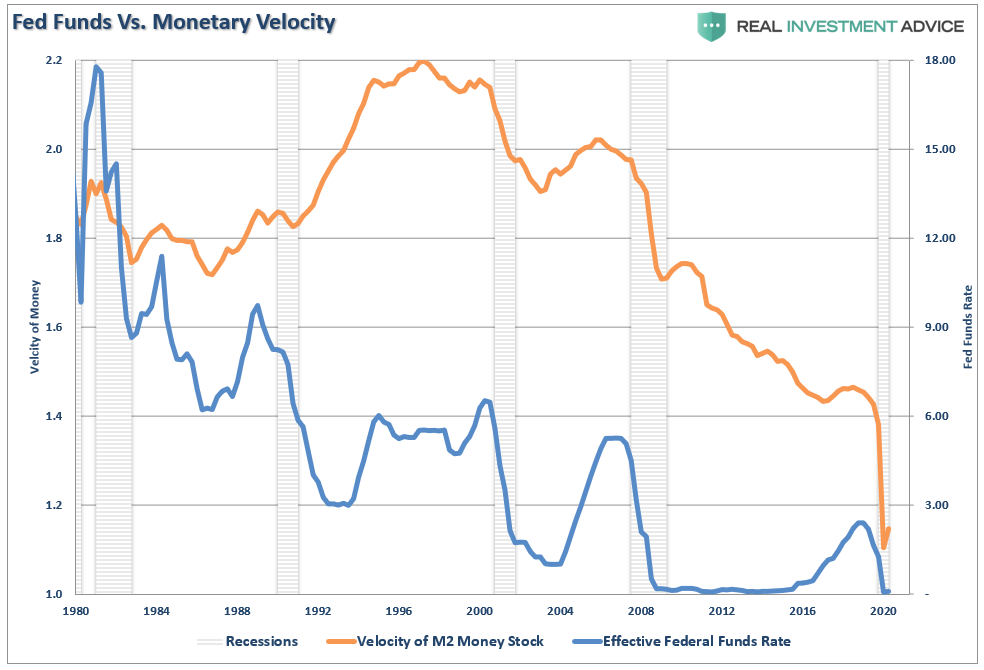

However, it isn’t just the expansion of the Fed’s balance sheet, which undermines the strength of the economy. It is also the ongoing suppression of interest rates to try and stimulate economic activity.

In 2000, the Fed “crossed the Rubicon,” whereby lowering interest rates did not stimulate economic activity. Instead, the “debt burden” detracted from it. (More on this in a moment)

As monetary interventions increased, the “transmission system” became more fractured as the “wealth gap” expanded. Despite perennial hopes that economic growth and inflation would arise from lower rates, more government spending, and increased “accommodative policies,” each iteration led to weaker outcomes.

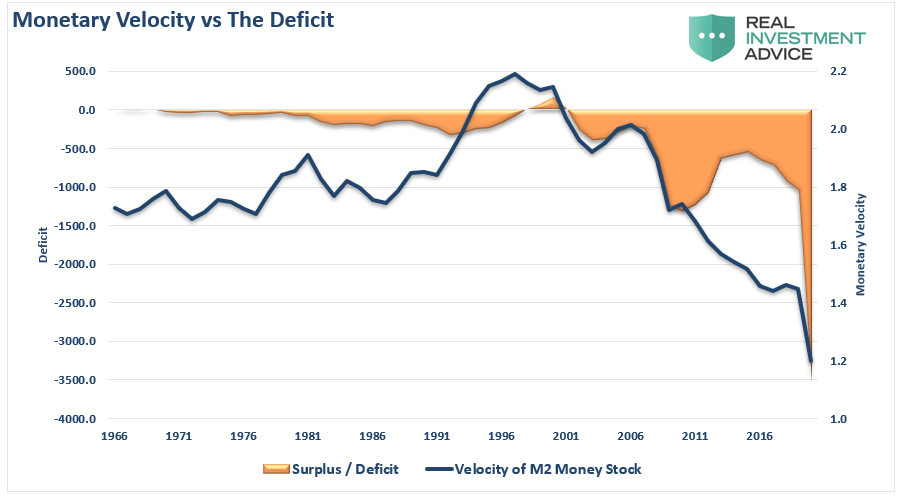

To illustrate the last point, we can compare monetary velocity to the deficit.

To no surprise, monetary velocity increases when the deficit reverses to a surplus. Financial surpluses allow revenues to move into productive investments rather than debt service.

The problem for the Fed is the misunderstanding of the derivation of organic economic inflation.

Productive Vs. Non-Productive Spending

Since 1980, there has been a shift in the economy’s fiscal makeup from productive to non-productive investment. To explain this concept, we can take a page from Dr. Woody Brock’s “American Gridlock” to explain the difference.

Country A spends $4 Trillion with receipts of $3 Trillion. This leaves Country A with a $1 Trillion deficit. In order to make up the difference between the spending and the income, the Treasury must issue $1 Trillion in new debt. That new debt is used to cover the excess expenditures, but generates no income leaving a future hole that must be filled.

Country B spends $4 Trillion and receives $3 Trillion income. However, the $1 Trillion of excess, which was financed by debt, was invested into projects, infrastructure, that produced a positive rate of return. There is no deficit as the rate of return on the investment funds the “deficit” over time.

Doing It Wrong

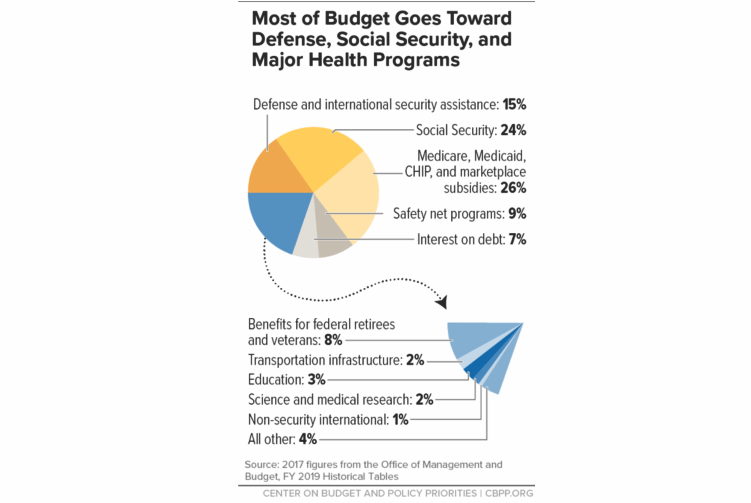

As discussed in “The Failing Theory Of MMT:”

“The problem is government spending has shifted away from productive investments. Instead of things like the Hoover Dam, which creates jobs (infrastructure and development), spending shifted to social welfare, defense, and debt service, which have a negative rate of return.

According to the Center On Budget & Policy Priorities, nearly 75% of every tax dollar goes to non-productive spending.”

In other words, the U.S. is “Country A.”

However, since that article was published, the debt swelled by $6.2 trillion in 2020. In an economy saddled by $82 Trillion in debt, the debt is no longer productive as more debt is issued to cover ongoing spending needs. This is why “monetary velocity” began to decline as total debt passed the point of being “productive” to becoming “destructive.”

The Federal Reserve problem is that due to the massive levels of debt, interest rates MUST remain low. Any uptick in rates quickly slows economic activity, forcing the Fed to lower rates and support it.

With the economy set to push a $4.2 Trillion deficit in 2020, the deficit’s deflationary pressure will continue to erode economic activity. As noted, even if the Fed does manage to get a spark of inflation, which would push interest rates higher, the debt burden will lead to an economic recession and deflationary pressures.

Why Sending Money To Households Won’t Create Inflation

This time is different because we are sending money directly to households.

Such is the underlying sentiment behind a universal basic income and its impact on economic growth. Unfortunately, it merely isn’t true.

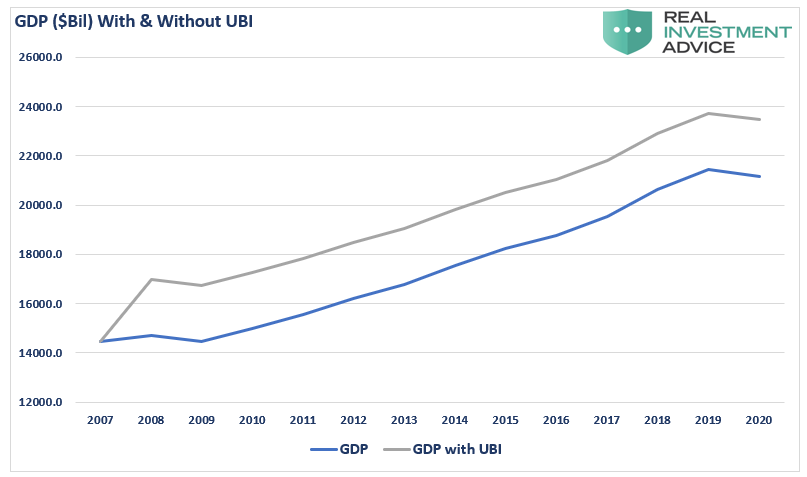

We can run a hypothetical example using GDP from 2007 to the present. (I am using estimates of -1.1% for 2020 GDP growth) In 2008, in response to the “Financial Crisis,” Congress passes a bill providing $1000/month ($12,000 annually) to 190 million families in the U.S.

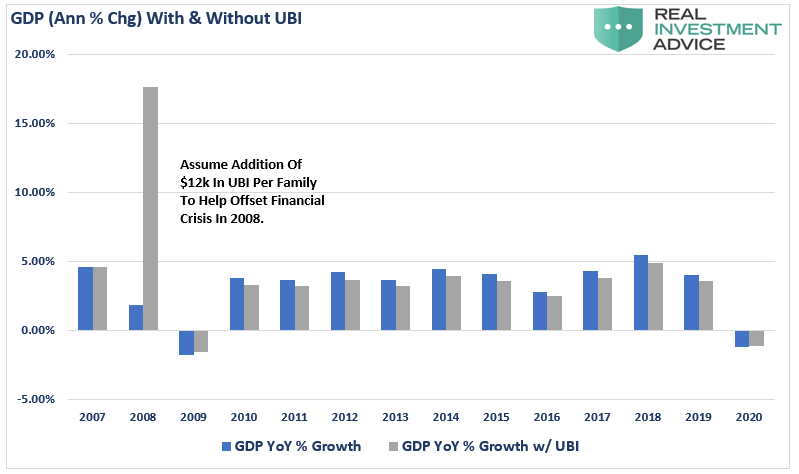

The chart below shows the economy’s annual GDP growth trend assuming the entire UBI program shows up in economic growth. For those supporting programs like UBI, it certainly appears as if GDP rises to a higher level.

However, such is an illusion. When you look at the annual rate of change in economic growth, which is how we measure GDP for economic purposes, a different picture emerges. In 2008, when the $12,000 arrives at households, GDP spikes, printing a 17% growth rate versus the actual 1.81% rate. Such was also be coincident with a short-term spike in inflationary pressures.

However, in the next year, the growth, along with inflation, disappears.

The reason is that after UBI flows into the system, the economy normalizes to a new level after the first year. Also, notice that GDP grows at a slightly slower rate as the dollar changes to GDP at higher levels print a lower growth rate.

Using the money supply as a proxy, we can see that increased money supply does not increase measured inflation.

What we find is since 1980, increases in the money supply tend to precede periods of below-average inflation. As noted, this is due to the “debt burden” and non-productive investment of increased money supply.

Deflation Remains The Risk

The debt problem remains a massive risk of monetary to fiscal policy. If rates rise, the negative impact on an indebted economy quickly depresses activity. More importantly, the decline in monetary velocity clearly shows that deflation is a persistent threat.

Treasury&Risk clearly explained the reasoning:

“It is hard to overstate the degree to which psychology drives an economy’s shift to deflation. When the prevailing economic mood in a nation changes from optimism to pessimism, participants change. Creditors, debtors, investors, producers, and consumers all change their primary orientation from expansion to conservation.

- Creditors become more conservative, and slow their lending.

- Potential debtors become more conservative, and borrow less or not at all.

- Investors become more conservative, they commit less money to debt investments.

- Producers become more conservative and reduce expansion plans.

- Consumers become more conservative, and save more and spend less.

These behaviors reduce the velocity of money, which puts downward pressure on prices. Money velocity has already been slowing for years, a classic warning sign that deflation is impending. Now, thanks to the virus-related lockdowns, money velocity has begun to collapse. As widespread pessimism takes hold, expect it to fall even further.”

No Real Options

There are no real options for the Federal Reserve unless they are willing to allow the system to reset painfully.

Unfortunately, given we now have a decade of experience of watching monetary experiments only succeed in creating a massive “wealth gap,” maybe we should consider the alternative.

Ultimately, the Federal Reserve, and the Administration, will have to face hard choices to extricate the economy from the current “liquidity trap.” However, history shows that political leadership never makes hard choices until those choices get forced upon them.

Most telling is the current economists’ inability, who maintain our monetary and fiscal policies, to realize the problem of trying to “cure a debt problem with more debt.”

The Keynesian view that “more money in people’s pockets” will drive up consumer spending, with a boost to GDP being the result, has been wrong. It hasn’t happened in 40 years.

We fear the ongoing policies will continue to lead to further social instability and populism. Such has been the result in every other country which has run such programs of unbridled debts and deficits.

As Dr. Woody Brock aptly argues:

“It is truly ‘American Gridlock’ as the real crisis lies between the choices of ‘austerity’ and continued government ‘largesse.’ One choice leads to long-term economic prosperity for all; the other doesn’t.”

Take your pick.

But 2021 will likely be a disappointment to those expecting more robust economic growth and inflation.

Related: The Illusion Of Soaring Savings Amid Rising Economic Uncertainty