In 2002 the UK Government announced the beginning of a £12.7 billion NHS National Programme for IT . The aim was seemingly simple: to replace paper medical records with a centralised national electronic database, allowing a patient from Manchester to walk into a hospital in London and find all their details readily available online in one place.

At the time, this transformation was meant to constitute the the most extensive, and expensive, IT healthcare development of its kind in the world. “The possibilities are enormous if we can get this right,” Tony Blair promised whilst clearly overlooking the possibility of getting it wrong. Nine years later, in September 2011 the government announced that the scheme would be scrapped.

That £12.7 billion investment into nothing is now dwarfed by the UK Test and Trace System that has so far cost £37 Billion, which is significantly more costly than getting a sustainable human presence on the Moon.

All over the the world our organisations are experiencing profound change. The most common way to react to that is some kind of transformational change programme.

The hallmarks of these programmes are big, 2-5 year initiatives with a number of drops and a greater number of consultants. The first release is usually many months, sometimes years away.

According to Barry O’Reilly, the growth of investment in digital transformation is compounding at 18% year-on-year. By 2023, an estimated $7 trillion will be spent on these initiatives annually. To put that in perspective, total US expenditure on healthcare for 2020 was about $4 trillion—during a pandemic.

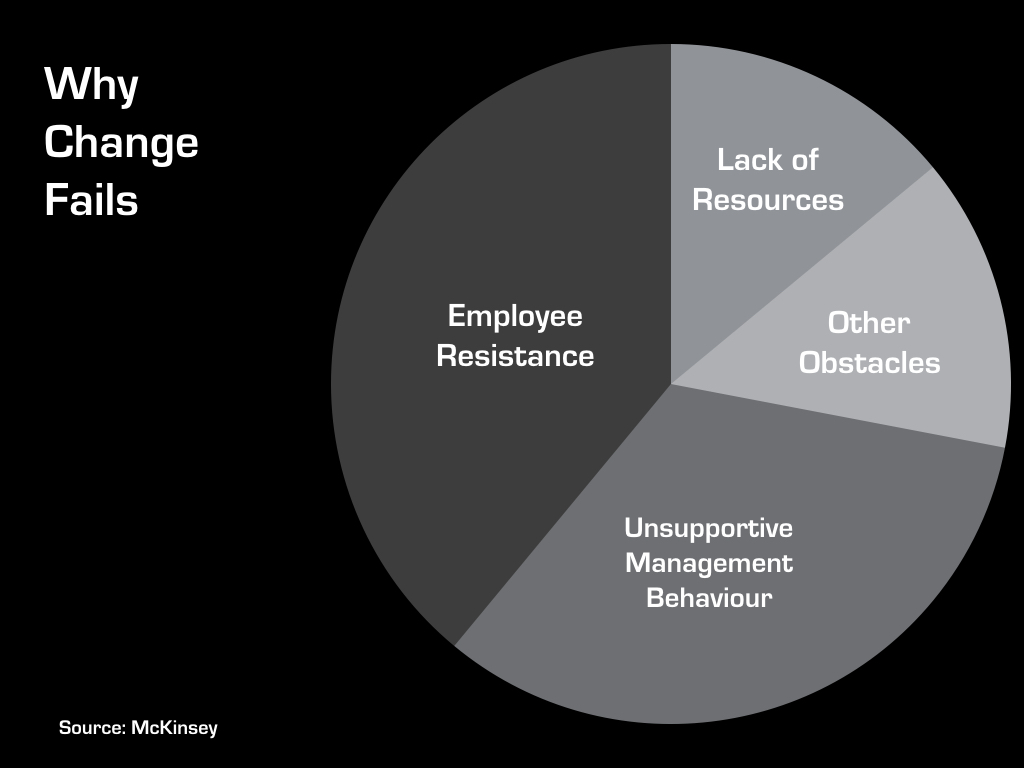

70% of these programmes will fail.

Why? Well, generally organisations don’t change. People don’t like it and don’t see why they should.

They adopt a culture – a unique blend of practices , beliefs and customs – that takes a long time to form and an age to break down.

Think how hard is to is to make a significant change to your personal life: quitting smoking , losing weight , ending a relationship. Multiply that difficulty by the number of employees you have and the hundreds and thousands of inter-relationships.

Just as your body is designed to fight a common cold, many of our cultures protect the organisational DNA from any irritant antibodies. Add something new and it’s likely to get rejected.

The challenge then is not to embark upon another change programme , but to hack your culture. To deliberately set out to mutate your organisational DNA and make it more receptive.

This isn’t easy and will be resisted. As David Burkus points out, research suggests that there is often a cognitive bias against new introductions – a “hierarchy of no”.

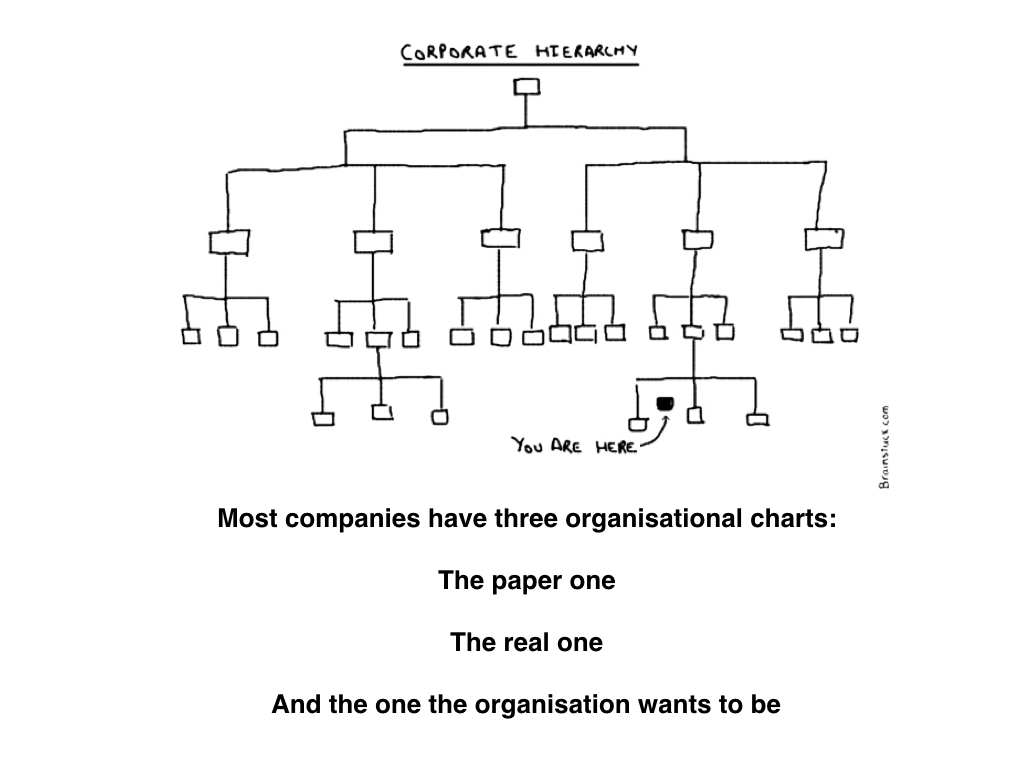

It’s going to be difficult for any of us to abandon our organisational structures – but there are ways you can create a “hierarchy of yes.”

As Tony Hsieh said – one of the biggest organisational barriers to change can be managers themselves. Hierarchies simply aren’t built to accommodate change. If change is going to happen, it often has to be project managed a year in advance.

We need a more democratic work environment. One where employees’ input is sought into areas once reserved for a select few.

It’s more than seeking inputs, though. If we are serious about hacking culture it means employees co-creating solutions with managers, not just feeding into meetings.

One of the mistakes ‘big change’ programmes often make is starting from the top. It’s almost impossible to innovate from the centre of the business. It’s easier to start at the outer edge and work your way in towards decision makers.

At Bromford Lab we’ve had to distinguish between wicked problems which might require widespread organisational change – and the smaller changes and innovations we can introduce from the edges of the organisation.

It’s why Jeff DeGraff argues for the creation of a “20/80 rule” to innovation: “It’s easier to change 20 percent of your organization 80 percent than it is to change 80 percent of your firm 20 percent,” he notes. Work your change from the outside in.

Keeping change locked up into a Lab or Hub type arrangement will only get you so far. You are going to need to infect emergent leaders if you want to bring about widespread change.

Leadership development programmes are a great way to make creativity part of everyone’s role. However they can often instill too much adherence to past organisational behaviour rather than a more disruptive future model.

Instead we need to develop more curiosity in our organisations. Socially curious employees are better than others at resolving conflicts with colleagues, more likely to receive social support, and more effective at building connections, trust, and commitment on their teams.

Giving people permission to be curious and to create new rules is the quickest way to eliminate fear , the biggest enemy of change.

There are big, bold ways to hack your culture – but there are lots of mini-hacks you can do that will make a huge difference. Most colleagues are annoyed with a limited number of things which breed mediocrity.

Our track record of introducing big change programmes is abysmal and yet your organisation is almost certainly about to embark on one right now.

The challenge is to think big about everything you want to change, but always to start small.

We’re obsessed with big change, but what if we’re underestimating the power of the small changes that lie more easily within our reach?