Last week I spent four and half hours in a room with my colleagues trying to get to the root of a problem.

Six colleagues: 27 hours of just thinking.

Einstein believed the quality of the solution you generate is in direct proportion to your ability to identify the problem you hope to solve.

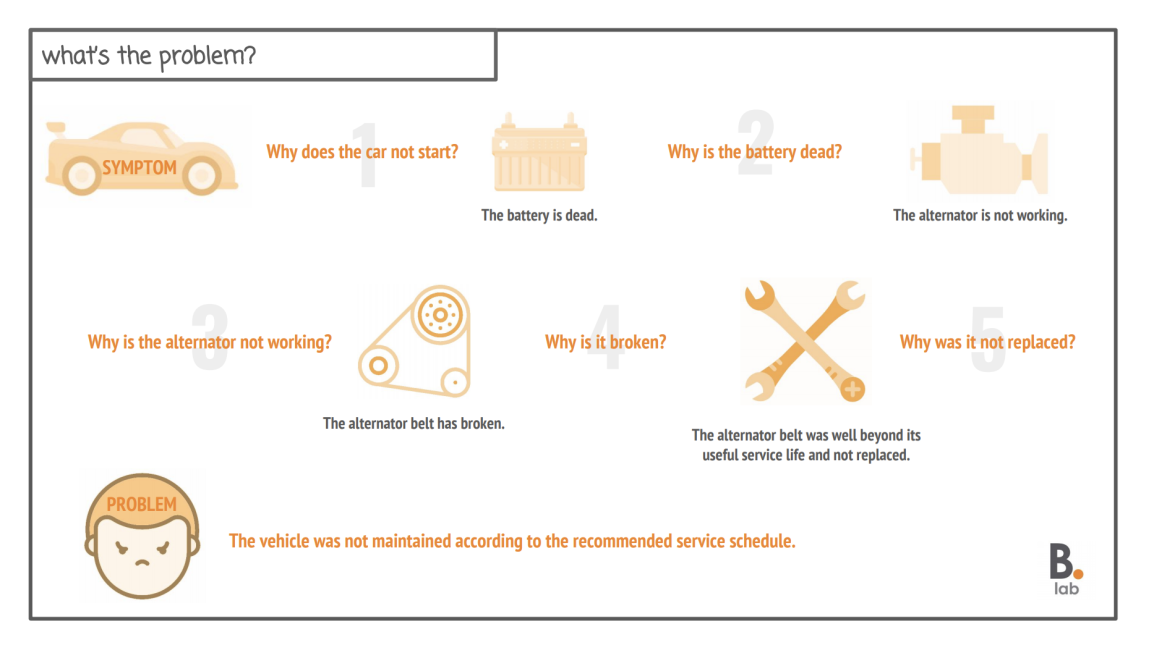

If you jump straight to answers you can miss the root cause entirely and embark on silver bullet solutions to the wrong problem. Your first idea really could be the worst idea.

Many of our organisations have a bias towards getting quick answers. We favour execution rather than contemplation. Great performance at work is usually defined as creating and implementing solutions rather than finding the best problems to tackle.

27 hours of thinking time – with no measurable outcome – is likely to be questioned as an indulgence.

At the same time many of us will have spent a lot of this week in meetings, most of which will be about generating activity rather than purposeful deliberation.

Why Agile Transformations Sometimes Fail

One of the issues I have with agile working is the presumption that teams using agile methods get things done faster. And fast is always good.

Fetishising speed results in just hurrying up. And once going fast is on the table, things quickly start falling off.

In the social sector addressing wicked problems is never going to be fast. It’s not just about a launching a new app, or customer ‘portal’.

We need to question some fundamental assumptions about how our businesses interact with citizens. And that may require unearthing some entirely new problems.

If we don’t nail the problem, and fully explore idea generation, we put all our efforts into actions.

This looks good in a project plan because it appears to reduce uncertainty. In reality our list of questions, our multiple lines of enquiry – should grow daily. But if you’re disciplined enough to be able to live with that ambiguity for a while, you usually end up with a better answer to your problem.

How To Solve Impossible Problems

I was reminded this week of the CIA technique for solving difficult problems. Phoenix is a checklist of questions developed by the Central Intelligence Agency to encourage agents to look at a challenge from many different angles.

It’s a deliberate and exhaustive approach to problem definition framed in three steps:

- Write your challenge. Isolate the challenge you want to think about and commit yourself to an answer, if not the answer, by a certain date.

- Ask the questions. Use the Phoenix checklist to dissect the challenge in as many different ways as you can.

- Record your answers. Information requests, solution, and ideas for evaluation and analysis.

You can see the full checklist here but I’ll pick on a few things organisations often completely miss:

- Why is it necessary to solve the problem?

- What benefits will you receive by solving the problem?

- What is the unknown?

- Suppose you find a problem related to yours that has already been solved. Can you use it? Can you use its method?

- What are the best, worst, and most probable cases you can imagine?

And then the plan…

- Can you separate the steps in the problem-solving process? Can you determine the correctness of each step?

- What creative thinking techniques can you use to generate ideas? How many different techniques?

- How will you know when you are successful?

Our organisations and customers would be better served if we played detective a little more. Detectives solve problems by finding the relationship between facts – they observe what others don’t. They eliminate the improbable or impossible.

In our workshop last week we considered how we could learn to solve problems like machines, endlessly mining our data to get more predictive

Imagine applying machine learning to a dataset across the social sector. Imagine the spread of machine learning to help solve the most challenging social problems in order to improve the lives of many.

Most of our organisations have a cultural bias for execution over thorough problem definition.

We are hardwired to doing things rather than purposeful contemplation. Developing a culture that has a bias towards questions, curiosity and deep thinking is necessary if we are to solve our most pressing problems.

Related: Remote Work Is Always Efficient But Efficient Isn’t Always Effective