The first half of 2023 saw the beginning of a banking crisis that will have repercussions for years to come, which will lead to a period of consolidation within the banking industry as well as a rethink of the role of banks in the US economy. During this period of significant stress, it is important to note that there are vast differences in the quality of banks as well as diverse operating models which will result in broadly varied outcomes. These nuanced differences are not appreciated by most investors and are not reflected in stock prices, making the sector uniquely attractive to long/short equity managers.

The main issue currently plaguing the industry was brought to the forefront of the market’s attention in March. Bank assets and liabilities are at an extreme duration mismatch, where balance sheets are filled with long-duration, low-yielding fixed securities and loans, while liabilities are shorter-term than previously anticipated. As interest rates rose, the value of their assets declined substantially. The issue was even worse than most investors first realized because a large percent of bank assets were classified as “held-to-maturity” and were not marked to market. Balance sheets artificially looked significantly healthier than they actually were.

The problem was compound as some banks had an outsized percentage of their deposits uninsured by the FDIC. These banks, with suspect liquidity, experienced significant deposit outflows, culminating with the headline failures of Silicon Valley Bank, Signature Bank and First Republic Bank. The chart below illustrates the historical nature of the events; even during the Great Financial Crisis of 2008, we didn’t see anywhere near the level of assets at failed institutions.

(Source: S&P Global, Bloomberg)

It was at this point that the Federal Reserve and the Treasury Department did 3 things to alleviate the short term liquidity squeeze on the industry. These included an implied FDIC guarantee on all bank deposits to stop runs on the banks, the Fed Bank Term Funding Program (BTFP) was created to assist banks having liquidity issues (but at a high interest rate), and helped arrange weak bank acquisitions by larger banks (potentially costing FDIC tens of billions). These measures effectively stabilized the short-term liquidity issues within the industry, but only temporarily.

Significant issues persist within the banking sector concerning the quality of their balance sheets, which in many cases have deteriorated further due to rising interest rates and bank’s decreased ability to generate profitability.

There are 3 ways to evaluate bank risk, which each have vastly different time periods.

- Liquidity, which we have addressed above.

- Solvency, assets verse liabilities, higher rates will continue to be a headwind on capital levels and the industry is ill prepared for any adverse credit events.

- Profitability

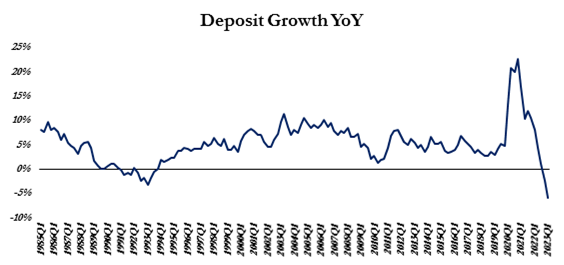

In examining the solvency of much of the banking industry, the duration mismatch of assets and liabilities has not gone away. Some banks have sold some of their long duration securities at losses to reduce their interest rate risk, but most of their assets are loans. With very few people paying off their mortgages or refinancing their maturing CRE debt, the average duration has been lengthening considerably due to the low rates prevalent at origination. At the same time, the industry is experiencing the largest contraction in deposits in over 50 years.

(Source: S&P Global, Bloomberg)

As concerns about bank runs spread across the industry, many banks repositioned their balance sheets to improve their liquidity profile. Notably, many of these actions have lowered capital levels and resulted in larger cash balances. Most importantly, competition for liquidity from other banks, money market funds or broader fixed income alternatives has forced banks to continue to pay up for liquidity. To put the competitive rate environment in perspective, recent available market rates include:

- Federal Home Loan Bank (FHLB): 5.50%

- Money Market Funds (MMF): 5.00%

- Fed Bank Term Funding Program (BTFP): 5.47%

- Fed Discount Window (DW): 5.25%

- Average US Certificates of Deposit (CD): 4.75%

- Average US Bank Deposit Rates: 0.54%

At the same time, the average securities yield of banks’ portfolios is approximately 2.75%.

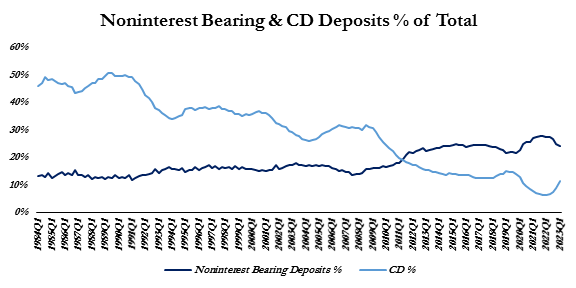

Unfortunately for the banking industry, depositors have awoken to the new reality that their excess cash balances can generate returns - resulting in a drastic remix out of non-interest bearing accounts into higher yielding alternatives, which may permanently change the industry.

Over the past 50 years, banks had become much less reliant on Certificates of Deposits (“CD”), to fund their balance sheet, yet this trend is beginning to reverse. A reversal which would have a drastic long-term impact on run-rate earnings.

(Source: S&P Global, Bloomberg)

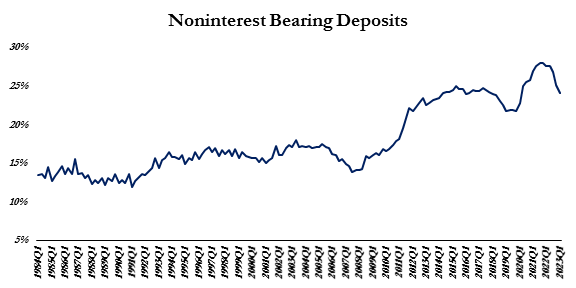

Non-interest bearing (NIB) deposits currently represent 24% of total deposits, down from a cycle peak of 28%. The average percentage of deposits that were non-interest bearing since 2011 is ~24%, signaling a return to pre-pandemic levels. However, a look at the pre-ZIRP (Pre-Great Financial Crisis environment) sheds some light on what the future might hold and brings with it, questions about the duration expectations of bank liabilities. With data going back to 1984, the average percentage of NIB deposits to total deposits between 1984 and 2007 was 15%.

(Source: S&P Global, Bloomberg)

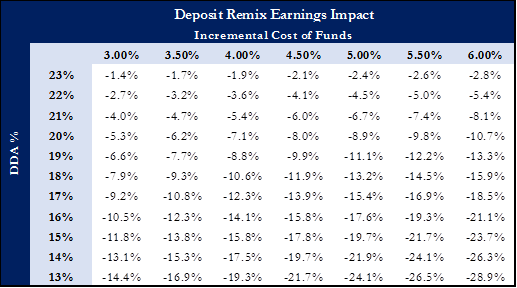

The sensitivity table below depicts what would happen to industry earnings if noninterest-bearing deposits continue to contract and are replaced with higher cost funding sources. For dramatic effect, if the industry were to revert to the pre-GFC average noninterest bearing deposit mix of 15% and is replaced with current market rates, industry earnings would decline by ~20%. This re-mix of liabilities will continue to pressure the industry’s earnings while current sell-side estimates misrepresent this reality.

(Source: S&P Global, Bloomberg)

Higher rates aren’t just impacting the liability/deposit side of bank balance sheets but the asset side as well. When interest rates go up, the market value of fixed income securities and loans decline. In addition, there are significant credit issues facing the industry at a time when the industry lacks adequate loss absorption buffers (reserves, capital and profits) should credit materially deteriorate.

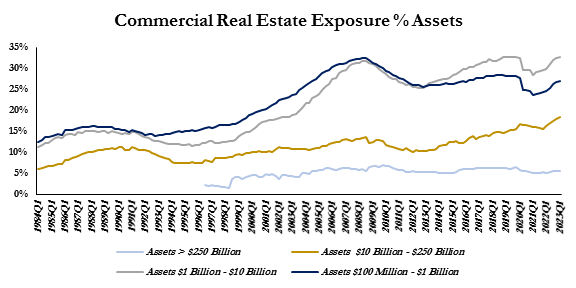

The biggest area of concern for most investors centers around Commercial Real Estate, especially office and retail properties in central business districts.

(Source: S&P Global, Bloomberg)

Commercial office real estate is being devastated by the shift to remote work where leasing activity in the 1st quarter dropped for the third straight quarter, sinking 42% below pre-pandemic levels. Large vacancy rates are reducing cash flows at a time when many loans will have to be renewed at substantially higher rates. Some industry experts are forecasting a 30% to 40% loss in value of commercial office real estate in many of the central business districts, which will result in many borrowers choosing to hand the keys to the bank rather than doing a ‘cash-in' refinancing.

As stress in the commercial real estate pipeline continues to build, it will take time before losses show up on bank balance sheets. The uncertainty around the frequency and severity of CRE losses is cutting off access to credit to all but the highest quality borrowers, which will have a more immediate impact on aggregate economic activity over the next 12 months.

It is important to differentiate between banks whose CRE exposures are genuinely at risk of incurring losses, while considering an investment in those companies whose headline CRE exposures might appear unfavorable, but whose actual risk profile is much lower than headlines suggest. Interestingly, despite outsized commercial real estate exposure, many small banks’ office exposure will have low charge-off rates as they are typically located outside of the major metropolitan areas. Additionally, small banks are typically more conservative in their underwriting, demanding more upfront equity and personal guarantees.

One area of the bank loan market that has yet to garner much attention is the traditional commercial and industrial (C&I) space. Commercial loans typically carry a variable interest rate and are underwritten based on the underlying cash flows of the organization, or they are collateralized by equipment value. With each passing month, commercial borrowers face incremental pressure as their interest expense increases while the current disinflationary real estate environment pressures margins and collateral values. Most commercial loans have been underwritten in an environment where companies’ income statements were incredibly healthy due to lower expense bases and higher fiscal support in the form of COVID relief. Most notably, we simply haven’t experienced a proper business cycle since the Great Financial Crisis and most business owners, similar to most investors, lack the knowledge to adapt to the realities of a slowing economy.

According to Epiq Bankruptcy, U.S. Chapter 11 bankruptcy filings have increased 68% in the first half of 2023 compared to a year earlier. The Bloomberg data below depicts the year-over-year change in bankruptcy filings for large and middle market enterprises, which shows a drastic increase in the first half of 2023. Recent data on the consumer shows an incredibly liquid and, for now, resilient US consumer which has supported economic activity in the first half of the year. With interest rates set to be higher for a while, small business default rates should continue to move higher.

(Source: S&P Global, Bloomberg)

While there are many banks that have outsized CRE exposures, regulatory controls have limited the percentage of a bank’s capital that can be exposed to CRE. However, there are no limits to a bank’s exposure to commercial credit. Many regional banks that are in the news for CRE risks have only 20% of their loan book in CRE with more than 50% of their loan book in commercial lending. For example, KeyCorp (NYSE:KEY), a $197bn asset bank based in the Midwest which has been in the news recently on liquidity and other concerns – not commercial lending related. The company has 14% of its loans in Commercial Real Estate while 54% of its loans are in commercial lending. Similarly, Regions Financial (NYSE:RF), a $150bn bank based in Alabama, has not been in the news often because its liquidity and capital position has been perceived as stable and thus has significantly outperformed the benchmark. Its CRE and Multi-Family loan book makes up 12% of total loans – with commercial loans at 53% of loans.

Summary

Unless interest rates drop dramatically, the banking crisis will lead to a high level of bank failures and consolidation within the banking industry over time. However, there are substantial value disparities between individual banks that are not understood by most investors and have not been reflected in stock price. Some banks will excel, including those with diversified business models that take advantage of market dislocation to gain market share or have superior credit profiles.

Related: A Case for Distressed Hedge Fund Strategies and How to Enhance Returns