How do you rate yourself for complying with Covid restrictions? Are you saint or sinner? Or are you, like most of us I suspect, somewhere in between?

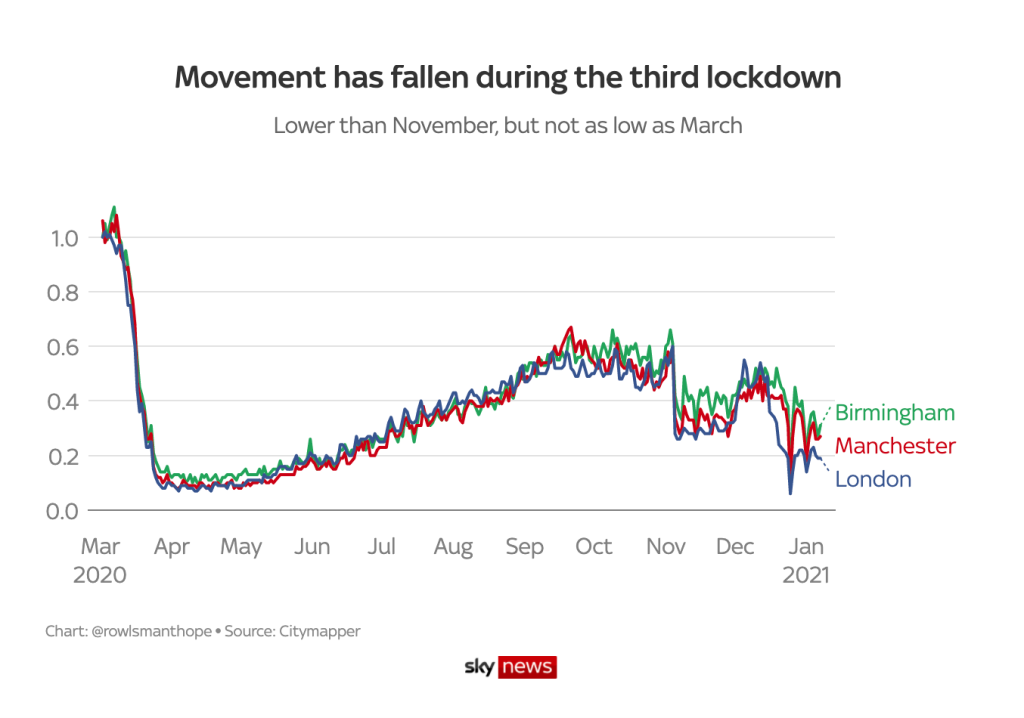

If you’ve noticed more traffic on the roads when you’ve been out walking or exercising, you could be forgiven for thinking that people aren’t taking this lockdown quite as seriously as the first one.

At first glance the statistics seem to bear that out. According to data provided by Citymapper, journeys during the first lockdown fell to less than 10% of pre-pandemic levels. This time round however, things are slightly different. As the graph below shows, movement has fallen since the latest lockdown was announced, but it isn’t down to the levels of March and April.

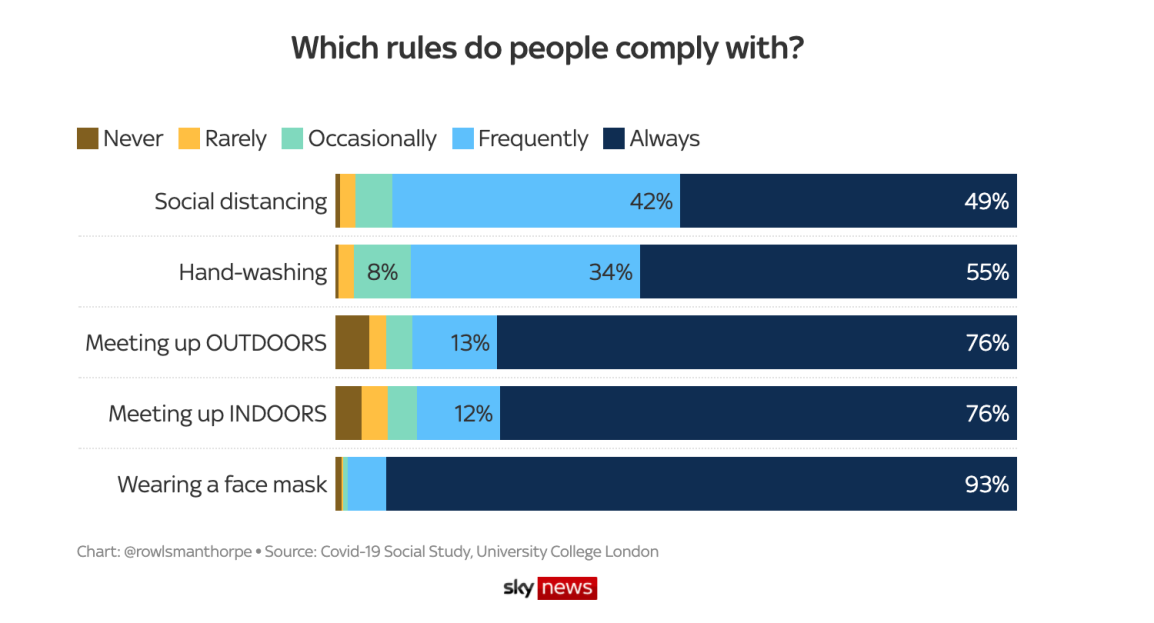

The Covid 19 Social Study show us that although we do follow the rules, we only follow them most – not all – of the time. The study, which has collected responses from more than 70,000 participants, found that the number of people reporting “majority compliance” – that is, following most or almost all of the rules – rose to 96% for the week ending 10 January 2021, which was the highest figure since last April.

However the number of people saying that they were in “complete compliance” with the rules is at just 56%.

So people know the rules and in general they want to follow them. On the other hand, large numbers of us have also become accustomed to bending them.

Hands up. I’ve bent them. I went to a cinema and to a restaurant in a Tier 2 area when I was in Tier 3. I’ve visited family members who live on their own but are outside a support bubble. I’ve also driven at 35mph in a 30mph zone and have on occasion cheated whilst doing e-learning tests at work.

95% of the time though – I think I’m a good citizen.

Only very few of us are completely compliant with all of the rules. Indeed, one of the strangest phenomenons of this pandemic has been the tendency for people to bemoan that the park or the shops are overcrowded and condemn this is as irresponsible behaviour, whilst they themselves also admit being there. ‘I was there, but it was clearly nothing to do with me’.

This shows that most of us don’t regard ourselves as rule breakers, we are just tweaking the rules to suit our personal circumstances. And we are much more accepting of our own breaches than we are of those of others.

This applies to all rules , not just COVID restrictions, and there are important lessons for any of us who design rules or procedures in the workplace, or are trying to encourage better social or health outcomes.

We often lament: “why do people take short cuts?”, “why do they eat stuff that’s bad for them?”, “why can’t they follow procedures?”, “why do they disable safety features?” The simple answer is because they are human, and they do whatever is easiest first.

The more complex reason involves the theory of risk compensation. Essentially everybody has their own level of acceptable or ‘target risk’. If they perceive that the risks of bending a rule are lower than their target risk then they will take additional risks (i.e shortcuts) in order to reap the benefits and rewards from doing so.

This is how desire pathways come into being. Nobody wants to be the first person to cut across the freshly laid grass just to save yourself a minute of walking. But once you see other people doing it, it becomes more and more acceptable. You join in.

So what can we do to get people to stop bending the rules?

First of all we need to stop demonising people for minor transgressions. As a piece by Stephen Reicher and John Drury in the British Medical Journal points out – the narrative of blame employed by the media and some politicians is both problematic and dangerous. Levels of adherence to Covid rules are astonishingly high – despite the hardships people are experiencing.

“The discrepancy between what people are doing and what we think people are doing is instructive and points to what is termed the availability effect. That is, we judge the incidence of events based on how easily they come to mind – and violations are both more memorable and more newsworthy than acts of adherence”.

The more we report – and exaggerate – the incidence of house parties, crowded shopping centres, and people not wearing masks, the more likely people are to “develop a biased perception of the level and type of violations, which runs the risk of becoming a self-fulfilling prophecy. If we believe that the norm is to ignore the rules, it may lead us to ignore them too”.

Secondly, following the rules is easier when you have the right resources. I have a job which means I can work from home easily. I have the space. I don’t have kids to look after. I have the income to buy the right technology. Data from the first lockdown showed that the most deprived were six times more likely to leave home and three times less likely to self-isolate, but that they had the same motivation as the most affluent to do so. The more deprived you are the more risks you have to expose yourself to. The only risk to many of the middle class is the risk from Ocado and Amazon delivery drivers.

Finally – people tend not to break rules when they are emotionally invested in them or they have been created by the community themselves. Indeed – it has been one of the great missed opportunities of the pandemic not to encourage more locally led dialogue and devolved decision making.

What makes a rule stick?

A good rule is clear, sensible, and not punitive or controlling. We adopt them when we believe they have value and make a better society, for us and others.

Hearing positive stories about people making sacrifices and sharing a social contract makes us more likely to react positively. Nobody wants to be an outlier.

Conversely, the more we hear talk of ‘covidiots’, anti-vaxxers, and pandemic fatigue the more likely we are to bend rules.

Ultimately , the stories we tell each other create the society we get to live in.