Written by: Eugene Steuerle

Source: Copied from Jean-Marc Natal & Philip Barrett, Interest Rates Likely to Return Toward Pre-Pandemic Levels When Inflation is Tamed, IMF Flog

In the recent New York civil fraud suit over Donald Trump’s inflated asset valuations, the court assessed damages mainly based on the favorable loan terms he obtained. Forget for the moment whether Trump did anything illegal and ask why he and other wealthy people and businesses want to borrow so much.

The answer rests partly on how monetary, regulatory, tax, and bankruptcy policies subsidize borrowing. In many years of this century, those policies have helped keep the expected cost of borrowing costs negative or close to negative. They have played a significant role in increasing wealth inequality in our economy and creating the extraordinary wealth valuation bubble we have been in for much of this century.

In a simple investment model, ignoring risk, a business will borrow if the return on investment is lower than the cost of borrowing. The investment may be in new buildings, equipment or existing assets. When the cost of borrowing is zero, a business in a riskless world will find a fully leveraged purchase of any asset that produces any positive return worth pursuing at any price.

If heavily leveraged, what may look like a lousy investment may look much better. For instance, an asset producing a real return of 3 percent, if purchased with 50 percent debt with zero borrowing costs, now has a return of 6 percent.

While it’s difficult for some to fully leverage a new purchase, such is not the case for those who have profitably built up equity over time. For instance, a firm with $1 billion in assets and no debt could easily borrow $200 million against a new asset base of $1.2 billion when it adds on a newly purchased asset worth $200 million.

Of course, risk puts some limits on this type of arbitrage, especially as interest rates and profitability of investments change over time. I’ll have to deal with that issue—and the extent to which that risk relates to our wealth bubble—at another time. Here, I want to emphasize all the ways that borrowing is subsidized.

How, for instance, can the cost of borrowing be zero or less if, say, the interest rate is positive? Four factors come into play: inflation, tax policy, bankruptcy protection, and additional government protections.

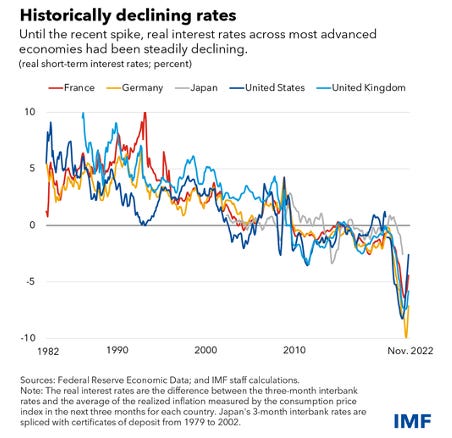

Inflation. In most advanced economies, the after-inflation interest rate charged on interbank loans was negative for most years of this century. Many households and investors today are sitting on loans with an interest rate lower than the inflation rate. That may not play out well when they have to roll over the loans at recently higher interest rates, but at least for a while, they get to borrow at no cost.

Tax laws. Congress allows taxpayers to deduct the inflationary component of the interest charge, not just the real component. It also allows taxpayers to deduct the real portion of the interest cost even when the return on an asset is deferred or excluded from tax.

Real estate investors often report little or income subject to tax, as Donald Trump bragged, because they manage to let their interest and other deductions offset their rental and other income. Their net income shows up as capital gains deferred from tax, often forever. Thus, they deduct both the inflationary and real components of their interest charges without paying tax on the inflationary and real increase in net worth.

Bankruptcy protections. Bankruptcies allow individuals and firms to push the cost of business failure onto others. The expected payments by a borrower and the expected returns for a lender must be reduced by the expected forgiveness of payments on those loans through bankruptcy or other reorganization.

Trump has never filed for personal bankruptcy, but his companies have filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy six times. Lenders often accept Chapter 11 bankruptcy because the assets, though valued lower than the face amount of remaining debt, still have a higher value than if they must be sold in personal bankruptcy. For instance, Trump’s bankrupt properties might still have a higher value with the “Trump” logo.

The bankruptcy laws effectively allow individuals and businesses to prevent losses from one investment having to be covered by gains and income from other investments.

Additional government protections. Finally, the Fed often assists borrowers by jumping in to prevent or limit the size of a financial crisis. While often good for the economy, it directly subsidizes leveraged investors. The Great Recession provided one of the most vivid recent examples, as the wealthy came out of that period with an even greater share of national wealth than before it began.

By overvaluing his assets, Trump further leveraged this market by getting an even lower interest rate based on his alleged amount of capital. For instance, the court case revealed his ability to borrow from Deutsche Bank’s private wealth management unit at lower interest rates than its commercial real estate division.

Firms and individuals with substantial wealth already start with a competitive advantage in making investments because, unlike the non-wealthy, they provide more collateral against bankruptcy. Individual agents at firms like Deutsche Bank also have an “agency” problem: an incentive to provide large loans to the wealthy that can generate big bonuses even if later bankruptcies cost the firm after those bonuses have been garnered.

When government policy offers easy money, many people want to get some of it legally or illegally. The eventual distribution of that easy money is seldom fair or efficient.

Related: Birkenstock Exceeds Revenue Expectations: Stylish Sandals Satisfy Fashion Enthusiasts