I have always loved sports, playing tennis and cricket when I was growing up, before transitioning to fan status, cheering for my favored teams from the sidelines. I also like finance, perhaps not as much as sports, but there are winners and losers in the investment game as well. Thus, it should come as no surprise that when the two connect, as is the case when teams are bought and sold, or players are signed, I am doubly interested. The time is ripe now to talk about how professional sports, in its many variations around the world, has blown a financial gasket, as you see teams sold for prices that seem out of sync with their financial fundamentals and players signed on contracts that equate to the GDP of a small country. In this post, that is my objective, and if get sidetracked, as a sports fans, I apologize in advance.

The Lead In

In its idealistic form, sports is about competition and the human spirit, and is divorced from money. That was the ideal behind not just the Olympic ban on athletes from being paid for performing, but also behind major tennis tournaments being restricted to just amateurs until 1968 and the entire collegiate sports scene. Both restrictions eventually fell, weighted down by hypocrisy, since the same entities that preached the importance of keeping money out of sports, and insisted that the players on the field could not make a living from playing it, engorged themselves on its monetary spoils. At this point, it seems undeniable that sports and money are entwined, and that trying to separate the two is pointless.

The Story Lines

As the walls between sports and money have crumbled, we have become used to seeing mind-boggling numbers on sports transactions, whether it be in the form on broadcasting networks paying for the rights to carry sporting events or player contracts pushing into the hundreds of millions. Even by those standards, though, the last few months have delivered surprises that have staggered even the most jaded sports-watchers:

- Player contracts: While player contracts have become bigger over time, the $776 million offer by Al-Hilal, a Saudi team, to Kylian Mbappe, the French superstar on contract with PSG, for a one-year contract to play with the team was eye-popping in magnitude. While Mbappe turned down the offer and is considering a ten-year deal with PSG, the numbers involved in the Al-Hilal deal are almost impossible to justify on purely economic terms. In parallel, as the 2023 baseball season winds down, questions about which team would sign Shohei Ohtani, its best player, and for how much were widely debated in the media.

- Sports franchise transactions: In 2023, the Washington Commanders, an NFL team with a decidedly mixed record on the field and a history of controversy around its name and owner, was sold for over $6 billion to a consortium, making it the highest priced sports franchise transaction in history. It followed a decade or more of ever-rising prices for sports franchises around the world, from the Premier League (soccer) in the UK, to the IPL (cricket) and across professional sports in the US.

- Sport disruptions: The last year has also brought threats to sports franchises, striking at their very existence. The Saudi team bid for Mbappe reflected a broader attempt by the country to disrupt professional sports, with professional golf, in particular, in the cross hairs. When LIV made its bid by signing up some of the best-known golf players in the world to play in its tournaments, few gave it a chance of success against the PGA, but in 2023, it was the PGA that conceded the fight in the money game.

- Broadcasting upheaval: As the revenues from sports has shifted from the playing fields to media, it is the size of the media contracts that determine how lucrative a sport is. In 2021, we saw the NFL, the richest franchise in the world, enter into new media contracts to cover the next decade of broadcasting rights for the sport. These contracts are not only expected to bring in a staggering $114 billion in revenues to the NFL in the next decade, but in a reflection of the times, they are split among four different broadcasters (ESPN, CBS, NBC and Fox), with Amazon Prime picking up the slack. The increasing importance of streaming in the media business was illustrated when the IPL, India’s cricket league, sold its media rights for the next five years for television broadcasting to Star India, a Disney-owned subsidiary, for roughly $3 billion, and the streaming rights for the same period to Viacom18, a Reliance-controlled joint venture, for about the same amount.

While these stories cover disparate parts of sports, and the only thing they share in common is the explosively large financial numbers, I will argue, in this post, that they represent an acceleration in a phenomenon that will change how these sports will get played and watched.

Rising Franchise Prices

Even a casual follower of the news on sports franchises changing hands, no matter what the sport, must have noticed the surge in the pricing of sports franchises, with little or no obvious connection to team success on the field; the Washington Commanders, the target of $6 billion acquisition, have won 63 games, while losing 97, in the last decade. In fact, the five highest prices paid for sports teams have all be paid in the last two years, as can be seen in the list of ten most expensive sports franchise transactions in history:

Team |

League |

Year |

Price (in $ billions) |

|---|---|---|---|

Washington Commanders |

NFL |

2023 |

$6.05 |

Chelsea |

Premier League |

2022 |

$5.30 |

Denver Broncos |

NFL |

2022 |

$4.70 |

Phoenix Suns |

NBA |

2023 |

$4.00 |

Milwaukee Bucks |

NBA |

2023 |

$3.50 |

New York Mets |

MLB |

2020 |

$2.40 |

Brooklyn Nets |

NBA |

2019 |

$2.40 |

Carolina Panthers |

NFL |

2018 |

$2.20 |

Houston Rockets |

NBA |

2017 |

$2.20 |

Los Angeles Dodgers |

MLB |

2012 |

$2.00 |

These high prices, though, represent the continuation of a trend that we have seen over the last few decades in franchise pricing, with the graph below looking at every major sports transaction between 1998 and 2023:

As you can see, transaction prices for sports franchises have been marching upwards for the last two decades, with NBA and NFL teams registering the biggest increases, but have seen breakaway surges in the last few years.

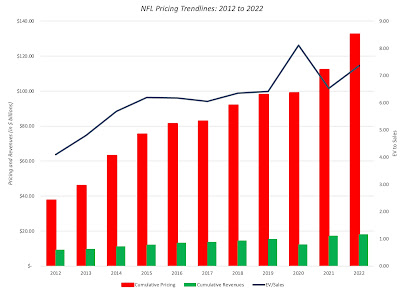

Some of you may be familiar with the Forbes annual listings of the most valuable teams in the world, and you may have wondered how they value sports teams. The truth, and I will clarify what I mean shortly, is that Forbes does not value sports franchises, but prices them. Since Forbes gets draws on actual transaction prices as guidance in their estimates, the pricing that Forbes attaches to teams has risen with transaction prices. In the graph below, for instance, I report the cumulative pricing of all NFL teams, as estimated by Forbes, from 2012 to 2022:

The collective pricing of all NFL teams, according to Forbes, has risen from $37.6 billion in 2012 to $132.5 billion in 2022. In fact, I will be willing to predict that given the Washington Commanders transaction, the pricing of every NFL team on the Forbes list will be higher in 2023.

With the pricing process in mind, it is instructive to look at the collective pricing, in millions of US dollars, of global sports franchises, as of the most recent updates from 2022 and 2023:

| Cumulative Pricing (in $ mil) | Highest Priced | Lowest Priced | |

|---|---|---|---|

| NFL (US Football) | $132,500 | $7,640 | $4,140 |

| NBA (Basketball) | $85,910 | $7,000 | $1,600 |

| MLB (Baseball) | $69,550 | $7,100 | $1,000 |

| NHL (Hockey) | $32,350 | $2,200 | $450 |

| MLS (US Soccer) | $16,200 | $1,000 | $350 |

| Premier League (To 20) | $30,255 | $5,950 | $145 |

| IPL (Indian Cricket) | $10,430 | $1,300 | $850 |

The NFL is the most valuable franchise in the world, in terms of collective pricing of all of its teams, followed by basketball and baseball. The collective pricing of all soccer teams around the world may actually be close to or even exceed the pricing of baseball or basketball teams, but just the top 20 Premier League teams have a pricing of about $30 billion. The ten teams that comprise the IPL, the Indian cricket league, have a collective pricing in excess of $10 billion. One interesting difference across franchises is the differences between the highest and lowest priced franchises, with the NFL having the smallest difference, and we will talk about how the way broadcasting revenue are shared can explain this divergence across sports franchises.

Finally, there is a subset of sports franchises that are publicly traded, but it is a very small one. Among US sports franchises, the one that comes closes is Madison Square Garden Sports, which in addition to owning the arena (Madison Square Garden) also owns the New York Knicks (NBA) and the New York Rangers (hockey), but it is closely held, with the Dolan family firmly in control. Outside of the US, Manchester United is the highest-profile example of a publicly traded company, but it too is closely held, with control in the hands of the Glazer family. There are a few European soccer teams that are publicly traded, but they all tend to be closely held, with light liquidity.

Price vs Value

If you find me finicky, when I label the Forbes estimates for franchises as prices, rather than values, it is best understood by contrasting price and value, two words that, at least to me, mean very different things and require different mindsets:

As you can see from the picture, while value is driven by familiar fundamentals (cash flows, growth and risk), price is determined by demand and supply, which, in turn, are driven by mood and momentum, behavioral factors that don’t play a key role in determining value. I used this contrast, a few years ago, to classify investments and talk about price and value with each one:

As you can see, collectibles and currencies can only be priced, and while commodities may have an aggregate fundamental value, they are more likely to be priced than valued. It is only with assets that are expected to generate cashflows in the future that value even comes into play. A company or a business can be valued, and that value will reflect its capacity to generate cash flows in the future, but it can also be priced, based upon what others are paying for similar companies. In fact, almost every investment philosophy can be framed in terms of whether you believe that there can be a gap between value and price, and when there is a gap, how quickly it will cause, as well as catalyst that cause that closing.

There is a sub-grouping of assets, though, that is worth carving out and considering differently, and I will call these trophy assets. A trophy asset has expected cash flows, and can be valued like any other asset, but the people who buy it often do so, less for its asset status and more as a collectible. Powered by emotional factors, the prices of trophy assets can rise above values and stay higher, since, unlike other assets, there is no catalyst that will cause the gap between price and value to close. So, what is it that makes it for a "trophy assets"?

- Emotional appeal overwhelms financial characteristics: The key to a trophy asset is that the core of its attraction, to potential buyers or investors, lies less in business models and cash flows, and more in the emotional appeal it has to buyers. That appeal may be only to a subset of individuals, but these buyers want to own the asset more for the emotional dividends, not the cashflows.

- It is unique: Trophy assets pack a punch because they are unique, insofar as they cannot be replicated by someone, even if that someone has substantial financial resources.

- It is scarce: For trophy assets to command a pricing that is significantly higher than value, they have to be scarce.

- It is bought and held for non-financial reasons: If trophy assets are opened up for bidding, the winning bidder will almost always be an individual or entity that is buying the asset more for its history or provenance, not its financial characteristics.

Examples of trophy assets can range the spectrum from legendary real estate properties, such as the Ritz Carlton in London, to publications like the Economist or the Financial Times.

Once an asset crosses the threshold to trophy status, you can expect the following to occur. First, it will look over priced, relative to financial fundamentals (earnings, revenues, cash flows), and relative to peer group assets that do not enjoy the same trophy status. Second, and this is critical, even as price increases relative to value, the mechanism that causes the gap to close, often stemming from a recognition that the you have paid too much for something, given its capacity to generate earnings and cash flows, will stop working. After all, if buyers price trophy assets based upon their emotional connections, they are entering the transaction, knowing that they have paid too much, and do not care. Third, and this follows from the firs point, the forces that cause the prices of trophy assets to change from period to period will have a weak or no relationship to the fundamentals that would normally drive value.

There is an interesting question of whether a publicly traded company can acquire trophy status, and while my answer, ten or twenty years ago, would have been a quick no, I have to pause before I answer it now. As many of you know, I have tried to value Tesla, based upon my story for the company, and the expected cash flows that emerge from that story, many times over the last decade. While some of the pushback has come from those who disagree with the contours of my story, and my expectations, some of it has come from people who have not only invested a large proportion of their wealth in the company, but have done so because they want to be part of what they see as a historical disruptor, one that will upend the way we not only drive, but live. The implication then is that Tesla will trade at prices that are difficult to justify, given the company's financials, that it will attract a subset of investors who receive emotional dividends from owning the stock and that short selling the stock, on the expectation that the gap will close, will be a perilous exercise.

Sports Franchises as Trophy Assets

When the Rooney family bought the Pittsburg Steelers, now a storied franchise in the most highly priced sports league (NFL) is 1932 for $2,500, it was very likely that they were buying it as a business, hoping to generate enough in ticket sales to cover their costs and earn a profit. After all, football (at least the American version) was a nascent sport, not widely followed, and with just a few teams and no organized structure. In fact, you can still view the Steelers as a business, and value them as such, but as we will argue in this section, that number will bear little resemblance to the $4 billion pricing that Forbes attached to the team. In fact, sports franchises across the world have already become, or are increasingly on the pathway to becoming trophy assets.

1. Prices disconnect from Fundamentals

To value a sports franchise as a business, it is worth examining how the revenues for franchises have evolved over time. Until the last 50 years, almost all of the revenues for sports franchises came from gate receipts collected from fans coming in to watch games, and the food and merchandise that these fans bought, usually at the games they attended. With television entering the picture, and streaming augmenting it, the portion of revenues that sports franchises get from media has become a larger and larger slice of the pie, as can be seen in the graph below, where we look at gate receipts, media revenue and other (merchandizing and sponsorship) revenues for all US sports franchises between 2006 and 2022:

As you can see, the overall revenues for sports franchises has grown between 2006 and 2022, with 2020 being the COVID outlier, but much of that growth has come from the media slice of revenues, as gate receipts have flatlined. This is clearly not just a US phenomenon, and you are seeing the same process play out in Europe (with soccer the big beneficiary) and in India (with cricket the winner).

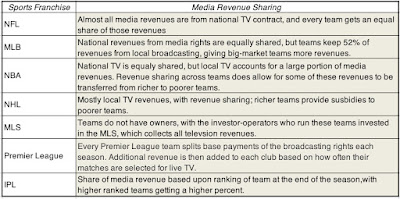

To value a sports franchise, you not only have to consider how much of a draw the team is at the stadium, but how much revenues the team gets from its media contracts, as well as merchandising and sponsorship revenues. While the gate receipts and merchandising revenues are significant, they are relatively easy to forecast, given history and ticket sales. Media revenues, though, are tricky, since they are determined partly by the size of the media market that the team operates in, and partly by how the sports franchise that the team belongs to shares its media revenues. In the US, for example, baseball teams get a significant portion of their broadcasting revenues from local TV rights, and as a consequence, teams in the biggest media markets (Yankees and Mets in New York, Dodgers in Los Angeles) have higher revenues than teams in smaller media market (Mariners in Seattle). In contrast, the media revenues for football (NFL) are mostly national, and those revenues are equally divided across the teams, resulting in more equitable media revenues across NFL teams. That difference explains why the divergence between the highest and lowest priced teams is greater in baseball than the NFL. The table below provides a comparison of how media revenues are shared across teams, by franchise:

While all of the franchises pay lip service to the need for balance, with large media-market teams subsidizing small media-market teams, there is wide variation across franchises in how they follow through on fixing that imbalance. Only the NFL has a strong enough system in place to create full balance, and that is partly because of the fact that almost all of its broadcasting revenues are national (rather than local) and partly because it is a league with a strong commissioner.

While revenues have risen, aided by richer broadcasting contracts, sports franchises have been faced with rising player costs; in almost every major sports franchise in the United States, player expenses account to 50% of revenues, or more, and they have risen over time. Once the other expenses associated with a team are netted out, the operating profits at sports franchises are, for the most part, moderate. Looking across sports franchises, you can see that the cumulated revenue and operating income numbers, in conjunction with the collective pricing of teams (as estimated by Forbes) in the most recent year:

While team financials tend to be opaque, Forbes estimated that the NFL, the richest sports franchise in the world, generated about $4.7 billion in operating profit on revenues of approximately $16 billion, in 2022. The NBA is the next-most profitable franchise, whereas baseball collectively struggles to make money. More to the point, if you use the Forbes pricing estimates for teams, note that four of the seven franchises (NFL, NBA, MLS and IPL) trade at 8-10 times revenues and at high multiples of operating income. It is true that there are tech companies in the market that trade at similar multiples, but those companies have extraordinary growth potential ahead of them and new markets to conquer. Even if you believe that media rights will continue to the the goose that lays the golden eggs for sports franchises, it is difficult to see how you justify these pricing multiples. To show that the disconnect between what buyers are paying for franchises, and what they are getting back in return, has been growing over time, I look at the pricing of NFL teams over time, relative to revenues at these teams (which include the richer media contracts) from 2012 to 2022:

Over the last decade, you can see that the pricing of NFL teams has risen from just over four times revenues in 2012 to more than seven times revenues in 2022. In short, NFL franchise prices are rising at rates that cannot be explained by revenue growth, richer media contracts notwithstanding, or higher profitability.

If you want to see how intrinsic valuation would work at a sports franchise, you are welcome to check out my intrinsic valuation of the Los Angeles Clippers, when Steve Ballmer offered $2 billion for that franchise in 2014. Looking at four scenarios, ranging from an extrapolation of the Clipper's 2012 financials to a best case scenario, where I modeled out a much larger media revenue stream, I got the following:

| Download spreadsheet |

I used the same framework to value the Washington Commanders today, and my values range from $2.5 billion, with current profitability, $2.7 billion, if you give them the median operating margin of an NFL team and a value of $4.5 billion, if you give them Dallas Cowboy level margins (the highest in the NFL). In short, getting to the $6.05 billion pricing with an intrinsic valuation is beyond reach.

2. A new breed of owners

At the start of this section, I mentioned the Rooneys buying the Pittsburg Steelers in 1932 for $2,500, and they continue to own the Steelers. While it is conceivable that they think of the Steelers as a business they own that has to continue to deliver earnings for them, much of the rest of the NFL has seen a changing of the guard, with new owners replacing the older holdouts. Many of these new owners are already wealthy, with their wealth accumulated in a different setting (real estate, private equity, venture capital), when they buy professional sports teams, and from the outset, it seems clear that they are less interested in turning a profit , and more in playing the role of team owner. To illustrate, I focus on the NBA, where there has been much turnover in the ownership ranks, with close to two-thirds of the teams acquiring new owners in the last two decades:

| Source |

As you browse this list, you will note that while many of the owners are billionaires, not counting their NBA team ownership, there are a few owners, towards the bottom of the list, whose wealth is primarily in their team ownership. Looking for trends, the more recent a sports franchise transaction, the more likely it is that the buyer is not just wealthy, but immensely so, and this pattern is playing out across the world.

So, why would these wealthy, and presumably financially savvy, individuals put their money into sports teams? In keeping with the saying that a picture is worth a thousand words, take a look at this picture of Steve Ballmer on the sidelines of a Clippers game:

To my untrained eye, it seems to me that the Clippers are not just another investment in Ballmer's portfolio. In 2014, at the end of my post on the Clippers, and after attempting in every conceivable way to find a financial justification why Ballmer would pay $2 billion for an NBA team that was a distant second to the other NBA team that played in the same city, I threw up my hands and concluded that Ballmer was buying a toy. By my estimated, it was an expensive toy that I estimated to cost about a billion (my estimate of the difference between the price he paid and my estimated value), but one that he could well afford, given his wealth.

In many ways, sports franchises are the ultimate trophy assets, since they are scarce and owning them not only allows you to live out your childhood dreams, but also gives you a chance to indulge your friends and family, with front-row seats and player introductions. In fact, it also explains the entry of sovereign wealth funds, especially from the Middle East, into the ownership ranks, especially in the Premier League. If you couple this reality with the fact that winner-take-all economies of the twenty-first century deliver more billionaires in our midst, you can see why there is no imminent correction on the horizon for sports franchise pricing. As long as the number of billionaires exceeds the number of sports franchises on the face of the earth, you should expect to see fewer and fewer owners like the Rooneys and more and more like the Steves (Cohen and Ballmer).

Consequences of Trophy Asset Status

If you are a sports fan, you may be wondering why any of this matters to you, since you are not a billionaire and are not planning to buy any teams, either as businesses or as trophy assts. I think that you should care because the trophy asset phenomenon is already reshaping how teams are structured, sports get played and perhaps what your favorite team will look like next year, when it takes the field.

- For Owners: For the owners of franchises that are not members of the billionaire club, there will be pressure to cash out, and the key to getting a lucrative offer is to increase the team's attraction to potential buyers, as toys. Adding a high-profile player, even one who is approaching the end of his or her playing life, can add to the attraction of a sports team, as a trophy, even as it reduces its quality on the field, as is moving to a city that a potential buyer may view as a better setting for their expensive toy (Oakland A's and San Diego Clipper or Charger fans, take note!). For billionaire owners of franchises, the reactions to owning an expensive toy that does not perform as expected, can range from impatience with managers and players, to trades driven by impulse rather than sports sense.

- For Players: As sports franchises become trophy assets, players become the jewels that add dazzle to these trophies. Not surprisingly, the superstars of every sport will be prized even more than they used to be, not just for what they can do on the field, but for what they can do for an owner’s bragging right. The recent billion dollar bid for Mbappe and the upcoming bidding war for Shohei Ohtani make sense from this perspective, and you should expect to see more mind-glowingly large player contracts in the future. To the extent that a player's trophy appeal is as much a function of that player's social media presence and following, as it is of performance on the field, you should expect to see sports players aspire for celebrity status.

- For Fans: If you are the fan of a sports franchise that is owned by someone to whom money is no object, you will have much to celebrate, as your team chases down and signs the biggest names in the sport. As a negative, if your team owner tires of their trophy asset, you may be stuck with the consequences of benign (or not so benign) neglect. If on the other hand, you happen to be a fan of the team that continues to be owned by an old-guard owner, intent on running the team as a business, you will find yourself frustrated as homegrown stars get signed by other teams. The old divide of rich teams/poor teams that was based on unequal media markets or stadium sizes will be replaced with a new divide between rich team owners and poorer team owners, where the latter still have to make their teams work as businesses, whereas the former do not.

In sum, if your concern has been that sports has become too business-like and driven by data, the entry of owners who are less interested in the business of sports and more interested in acquiring trophies may very well change the game, but at a cost, where sports becomes entertainment, where players and teams chase social media status, and what happens on the field itself becomes secondary to what happens off the pitch.

Related: In Search of Safe Havens: The Trust Deficit and Risk-Free Investments!