Several months ago, my middle school daughter and I traveled out of town to enjoy a different environment. From a home in Seattle, I worked virtually and she attended remote school. On the first day, we found the Wi-Fi connection strength very poor and panicked as my daughter struggled to dial into her first class. When she did get in, the connection lagged or online tools didn’t work or she was kicked out of the virtual classroom altogether. The whole experience left her near tears and frantic. But we fortunately had options to improve our situation like purchasing a Wi-Fi repeater and experimenting with different devices. I had the flexibility to reschedule my meetings to lessen the demand on the connection or, if all else failed, we could move to a different location with a stronger signal. That’s not the case for many unfortunate families in the Bay Area and the broader US who experience every single day what we experienced in one day.

Maria Elena Arteaga experienced similar challenges we did, and more, to educate her fifth grader and kindergartner through the Redwood City School District. The technology devices she had available and the ones provided to her children were inadequate to access the required education applications. The hotspot that was made available to her family was not strong enough to provide for two children attending remote school. While she was pleased with the assistance she received from the District, she’s concerned that her children’s education has been significantly set back. “This is costing a lot of problems with equity, since the families in our community don't have the necessary resources to be able to buy better computers or iPads,” Arteaga said through an interpreter. “We cannot offer a better experience for our students.” That’s why she’s chosen to work as a Parent Leader at Innovate Public Schools, a nonprofit organization working to make sure that low-income students and students of color students receive a world-class public education.

Jose Talavera, a Community Organizer at Innovate Public Schools, says there are many families just like Elena’s grappling with the same technology difficulties across the Bay Area, but especially with the issue of poor Wi-Fi connections. Many cannot afford the stronger Wi-Fi strength or unlimited access to accommodate all those who need it in the household. Chromebooks, which have been a staple in the classroom, cannot stand in for a computer when stronger computing power is needed for certain educational tools. “It’s not just the kids … that need to be connected,” said Talavera, “The parents too need access for teacher conferences and school board meetings. Access to information is limited for them and this is creating a divide in our community.”

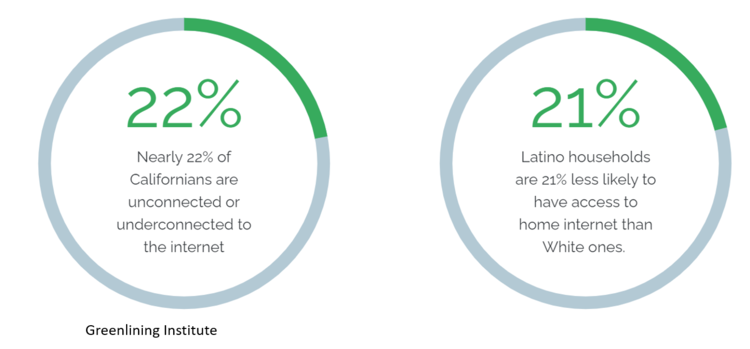

When did this digital divide start? “I would say the 1930s would be a good place to point to because that’s when redlining came about,” said Paul Goodman, Technology Equity Director, Greenlining Institute. The New Deal's Home Owners' Loan Corporation (HOLC) introduced policy to assess the risk to mortgage lenders and insurance companies by developing security maps of neighborhoods around the country. White, affluent neighborhoods were indicated with green lines suggesting a good credit risk, while black, ethnic and poor white neighborhoods were often indicated by red lines, suggesting a poor credit risk. Without adequate access to capital, redlined areas lacked the resources to build wealth at the same pace white, affluent areas were able to. “It’s technically illegal but you still see it, especially in the broadband space. When broadband came around, internet service providers looked around and said, ‘Where do we want to build our networks,’ and they decided, ‘We want to build in the areas with the highest profit,” said Goodman. As the providers continued to upgrade and maintain networks, these new maps look very similar to the old redlining maps of the 1930s, where broadband is good in more affluent areas and poor in less affluent neighborhoods. “A lot of folks try to frame this argument as about being urban versus rural. But it's really not. It's about folks who don't have internet because it's not available, or it's not sufficiently robust, or they can't afford it … And so what we need right now is a solution that's going to reverse decades of neglect.”

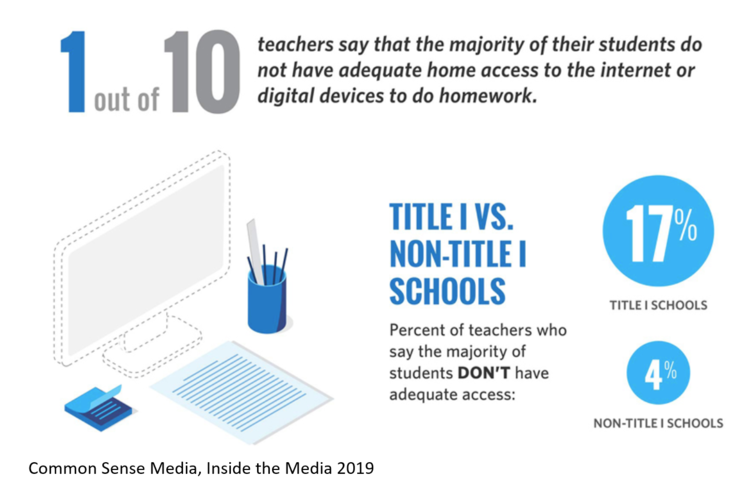

Fast forward to the twenty-first century, when technology seemed to take the classroom by storm, researchers saw another phenomenon. Common Sense Media, a national education nonprofit, published a report in September 2019 that showed that teachers avoided assigning homework that required the internet or technology when they knew some students did not have access at home, even when these students had technology resources outside the home. What this showed was a waste of existing Ed-Tech resources that would continue unless underserved families and teachers could be provided with technology resources at home. As schools turned to distance learning at the start of the pandemic, Common Sense Media estimated that 16 million kids, out of the estimated 51 million public school students, and about 400,000 teachers were experiencing the distance learning digital divide. “We found that the cost of closing it in the first year … was about $11 billion across the country,” said Amina Fazlullah, Equity Policy Counsel at Common Sense Media. “If the number sounds high, the reason is because to do distance learning in a robust way, you would need 200 download, and 10 upload Mbps (Megabits per second). Because you have multiple folks in the household, potentially more than one student or maybe a family member as well, that's going to require broadband service to do that type of distance learning work and avoid the interruptions,” said Fazlullah.

What would make a robust online learning experience? Nancy Poon Lue, Co-Founder of the Advanced Education Research and Development Fund says this varies significantly depending on the individual learning style and academic readiness of the student. “Teachers are working incredibly hard to try to replicate what they had been doing in classrooms and all the years before to try to translate that online. But it's actually important to shift away from that thinking of how do we take everything that happened in the classroom, and just put it on Zoom.” Lue said that research has shown three key factors that contribute to the best learning experience. First is flexibility with learning time and schedules that meets the needs of everyone in the household. Parents and guardians who are essential workers cannot support students during the day. Some students must share devices with family members. “Teachers really need to encourage stronger autonomy and engagement by setting up different options for families between the live synchronous learning that also works better for some students to be directly live with an instructor, or some of the asynchronous learning options,” said Lue.

The second factor is a stronger integration with technology apps, particularly in the elementary and middle school years. Data from in-classroom studies has shown that high quality technology applications have been helpful in many core subjects such as reading and math. “Many school districts have been using these apps with students in school buildings during specific times when school was in session. But given that we're now in this virtual environment, students or families really should be given direct access to these apps, and many have started to get them, but encouraged to use them much more frequently on their own to complement what is going on in the classroom,” said Lue.

The third factor needed to address learning loss due to the COVID learning environment is high-dose tutoring. Early research has shown that this learning loss has been greater than that experienced during the regular summer break. It’s longer and deeper which could create long-term damage to our most vulnerable students, including those from low-income families, those with disabilities and English language learners. This high-dose tutoring, which could be done one on one, or in small groups, but it can be done virtually. What we’ve learned from being shut down in our homes is that we can access tutors from anywhere virtually and by expertise. “We really need to address those learning gaps as quickly as possible. That type of tutoring needs to happen during the school year both as part of the regular school day and outside of school hours because of the time flexibility ... but especially during the summer we’re coming up on because of the learning losses that have happened since March,” said Lue.

What organizations are actively working to close this digital divide?

The California Emerging Technology Fund (CETF) was started in 2007 by the California Public Utilities Commission, out of the merger of AT&T and SBC and the merger of Verizon and MCI, to ensure the new entities delivered a public benefit. One of the many goals of the fund is to help low-income families find affordable internet rates. “One of the things that we have learned through our annual surveys … is that of the population that doesn't have internet at home, 70% of them don't know about affordable rates. And the companies, with few exceptions, don't promote that those are available. And then once you get to them, it's difficult,” said Susan Walters, Senior Vice President of CETF. With respect to the education digital divide, CETF focuses on public awareness and education. One is to help principals and teachers understand the role of technology in their school culture and in the classroom. “What we learned consistently is that 30 to 40% of the teachers weren't comfortable with technology. Some didn't even have an email account and their focus was very traditional.” Second, CETF educates parents by helping them understand the role they play in their children's education and how to manage that technology from interacting with the school, but also interacting with the child. “It’s like any process of raising children. There have to be rules, there have to be boundaries, there have to be agreements.”

In the end, internet connection is the critical piece. “If you have a device, you can have all the knowledge and you can have all the training device. But if you don't have a connection, that's really where the problem starts,” said Jon Walton, Chief Information Officer of County of San Mateo. Fortunately, the $900 billion Covid-19 Relief Bill passed by both houses of Congress in late December included broadband provisions to allow more Americans access to the internet. The bill reserves $7 billion for broadband connectivity and infrastructure, including $3.2 billion for a $50-a-month emergency broadband benefit for low-income households and those that have suffered a significant loss of income in 2020, and a $75-a-month rebate for those living on tribal lands. It also includes $1 billion in grants for tribal broadband programs, $300 million for rural broadband grants, and funds toward telehealth, broadband mapping, and broadband in communities surrounding historically Black colleges and universities.

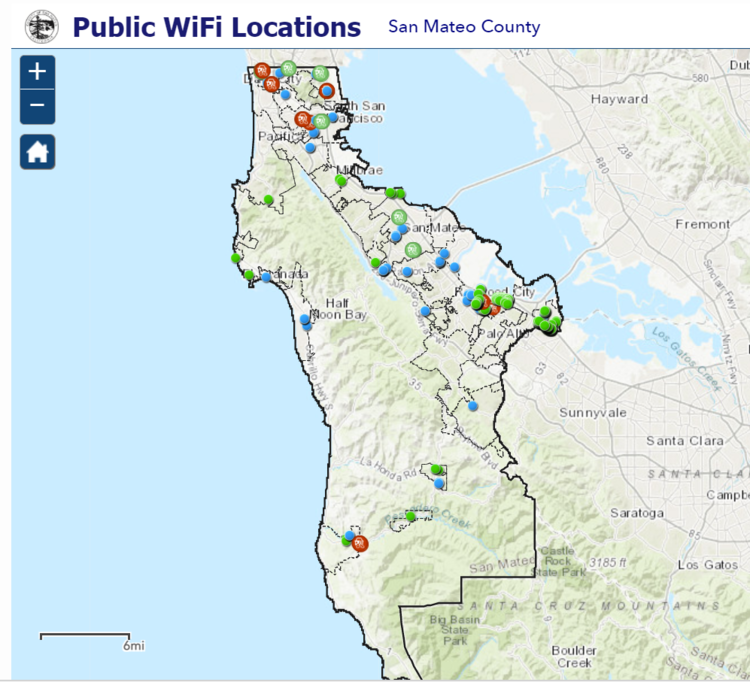

San Mateo County, while home to many of the wealthiest cities in the country, like Atherton and Menlo Park, is also home to less affluent cities and farming communities that struggle with internet access. This broadband access challenge creates not only distance learning challenges, but also public safety concerns. In 2014, the San Mateo County Board of Supervisors, recognizing that underserved communities could not afford unlimited data plans initiated the installation of 100 public Wi-Fi hotspots in community centers, libraries, and parks to create areas a kind of town square where people would come together. Before shelter-in-place, approximately 150,000 devices accessed the County public Wi-Fi network annually, resulting in about a million internet user-hours per month.

But with shelter-in-place, 100 town square hotspots would not be enough to satisfy the need. So the County Board of Supervisors set aside nearly $6 million out of the CARES Act to increase broadband accessibility across the county, working with school districts to create a needs map of to indicate where underserved students lived. While this step toward increased access is meaningful, the County has farther to go. Preliminary estimates indicate the true cost of closing the gap in San Mateo County to be closer to $100 million. Said Walton, “I think we as a society, we as a community, really need to address the fact that just like roads, and water and electricity, broadband access is a basic need that everyone should have equal access to and that we should invest in.”

Related: Why Nonprofit Investors Should Expect the Unexpected