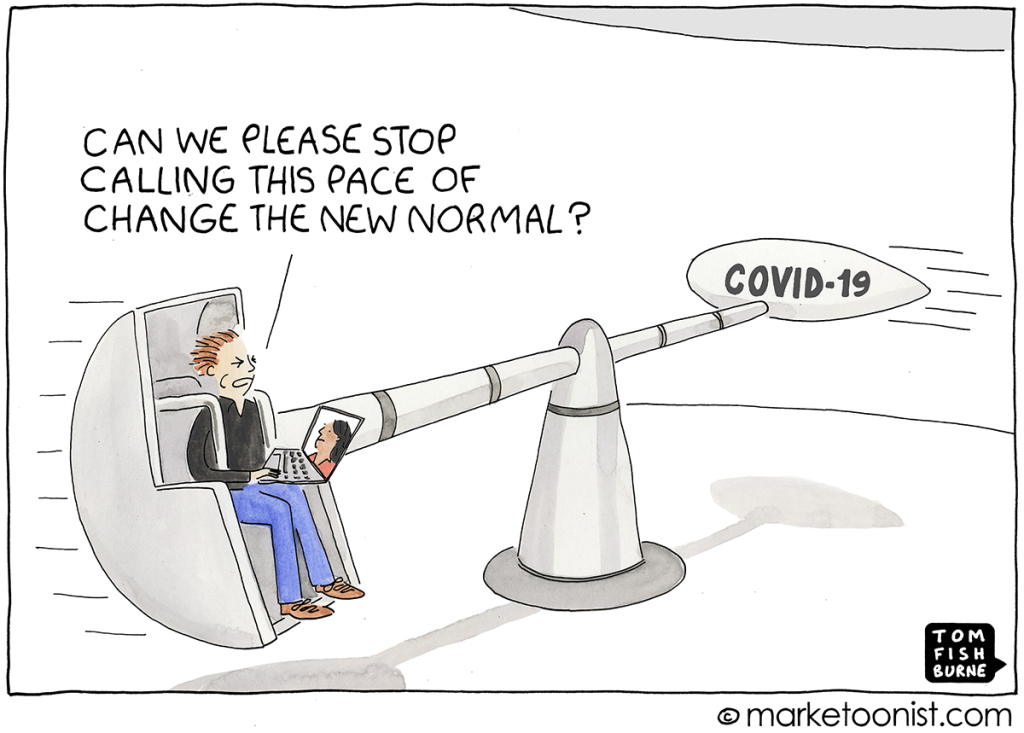

The latest cartoon by Tom Fishburne seems to sum up what a lot of people are feeling right now. As he writes, “In a chaotic year, many brands and businesses are relying on adrenaline only. Organizations can only run on those fumes for so long. Adrenaline-based speed can lead to burnout.”

I’d argue that we are not seeing speed as much as lots of activity. Organisations are busy, sure, but it’s a reflexive response to an era in which they have no control over anything, even down to when and where people work. In organisational design terms – we are all still out there panic buying toilet rolls and hand sanitiser.

One of the issues here is that legacy organisations are not designed for speed, it’s just not what they do. Many people who have set up internal accelerators or innovation labs ultimately fail as they run up against hard wired bureaucracy and hierarchy purposefully designed to crush any ideas that threaten the status quo.

In their report, Reinventing the organisation for speed in the post COVID era, McKinsey note that CEOs recognize the need to shift from adrenaline-based speed during COVID-19 to speed by design for the long run.

It calls for work to speed up in three ways:

Sped up and delegated decision making. This means fewer meetings and fewer decision makers in each meeting. They point out that some organisations are adopting a “nine on a videoconference” principle. (I’d suggest this is still a couple too many). Others are moving towards one to two-page documents rather than reports or lengthy PowerPoint decks.

Step up execution excellence. Just because the times are fraught does not mean that leaders need to tighten control and micromanage execution. Rather the opposite. Because conditions are so difficult, frontline employees need to take on more responsibility for execution, action, and collaboration.

Cultivate extraordinary partnerships. Working with partners is routine. But the speed of action only goes so far if other players in the ecosystem fail to move just as fast. The connected world is breaking down the traditional boundaries between buyers and suppliers, manufacturers and distributors, and employers and employees.

The building blocks at the base of all these things are, guess what, small empowered teams.

Is it finally the time that our organisations will make the shift to smaller teams, not just because of financial savings, but because of their increased effectiveness and productivity?

I’ve been an advocate of a the minimum viable team for a number of years. The concept of as few as people as possible – small enough to be fed on two pizzas, is attractive because it reduces social loafing and allows us to get off the hamster wheel of management and ‘work about work’. Once you’ve done it and moved away from managing lots of people it would take an almighty pay rise to tempt you back.

The Two Pizza Team was popularised by Jeff Bezos who in the early days of Amazon instituted a rule that every internal team should be small enough that it could be fed with two pizzas. The goal was, like almost everything Amazon does, focused on two aims: efficiency and scalability.

Its roots lie in the concept of the Minimum Viable Team which recognises that many companies spend an awfully long time thinking and planning to do something: longer than it takes to actually do the thing. It’s built on the premise of Parkinson’s Law – that work just expands to fill the time and resources available. The MVT idea is rather than layer on additional resources (that are ultimately wasteful) , you “starve” the team and make them pull only the necessary resources as and when they need them.

Most organisations reserve this structure, if they use it at all, for either DevOps type environments or hipster design or innovation teams. However it has a sound evidence base – after devoting nearly 50 years to the study of team performance, the Harvard researcher J. Richard Hackman concluded that four to six is the optimal number of members for a project team and no work team should have more than 10 members.

How many project teams do you know that have four to six members?

Remote work exacerbates this problem. It’s hard enough to run productive in-person meetings with lots of people in the best of times, but trying to foster engaging discussions with lots of virtual participants is nearly impossible.

Despite the rhetoric of agile small teams – the shift won’t happen overnight as there’s a genuine question about what to do with all the people you might not need. I’d argue that post- COVID the immediate challenge is how we slow down to speed up.

We are in a new world with new challenges and we sometimes confuse operational speed (moving quickly) with strategic speed (reducing the time it takes to deliver value)—and the two concepts are very different. The more you can reduce organisational initiatives to a few key problems the more you can bridge the gap.

Do Fewer Things, Better. And Faster

No organisation, large or small, can manage more than five or six goals and priorities without becoming unfocused and ineffective, and it’s exactly the same for us as people.

The best organisations don’t try and do everything. They focus on a few differentiating capabilities — the things they do better than any other company.

This is not an either/or. IF we can reduce our priorities to a few key goals AND make small focussed teams the default way we operate , arguably we’d be a lot happier, healthier and more productive.

Related: Why Do Bad Ideas Spread So Easily?