“Scared money doesn’t make money” is an often-used phrase and one that has applications across myriad real life situations.

Take it from someone that lives in Las Vegas, this is a saying bandied about at the tables. While it is not gambling advice, there will be plenty of occasions when the scared money misses out on more money. Probably as many, if not more than the times in which the scared money is validated for being timid.

As for applying “Scared money doesn’t make money” to investing, a case can be made that being to adventurous will not bear fruit. Rather, it will have the opposite effect. Big drawdowns are punitive and that explains why so many market participants embrace low volatility investing.

That’s fine for some, but there’s also compelling evidence confirming that scared money won’t be rewarded in financial markets. In fact, eschewing timidity in financial markets can spin old advice on its head and potentially lead to greater rewards. Read on to discover why.

Buy Low, Sell High

“Scared money doesn’t make money” shares a crucial intersection with the old market advice “buy low, sell high.” As advisors know, that’s easier said than done.

Profits aren’t profits until they’re realized, but selling at highs isn’t all it’s cracked up to be because, as advisors and experienced investors know, just because one record is hit, doesn’t mean another isn’t right around the corner. Actually, as confirmed by the S&P 500 this year, records can arrive in bunches. The point is while selling at all-time highs may amount to taking profits, it can also mean leaving more profits on the table.

“On average, 12-month returns following an all-time high being hit have been better than at other times: 10.3% ahead of inflation compared with 8.6% when the market wasn’t at a high. Returns on a two-year or three-year horizon have been slightly better on average too,” notes Duncan Lamont of Schroders.

Advisors also know that risk assets don’t move up in straight-line fashion and bear markets or black swan events can and do occur. However, there’s a strong case for remaining invested over going to cash as new highs are achieved. History proves as much.

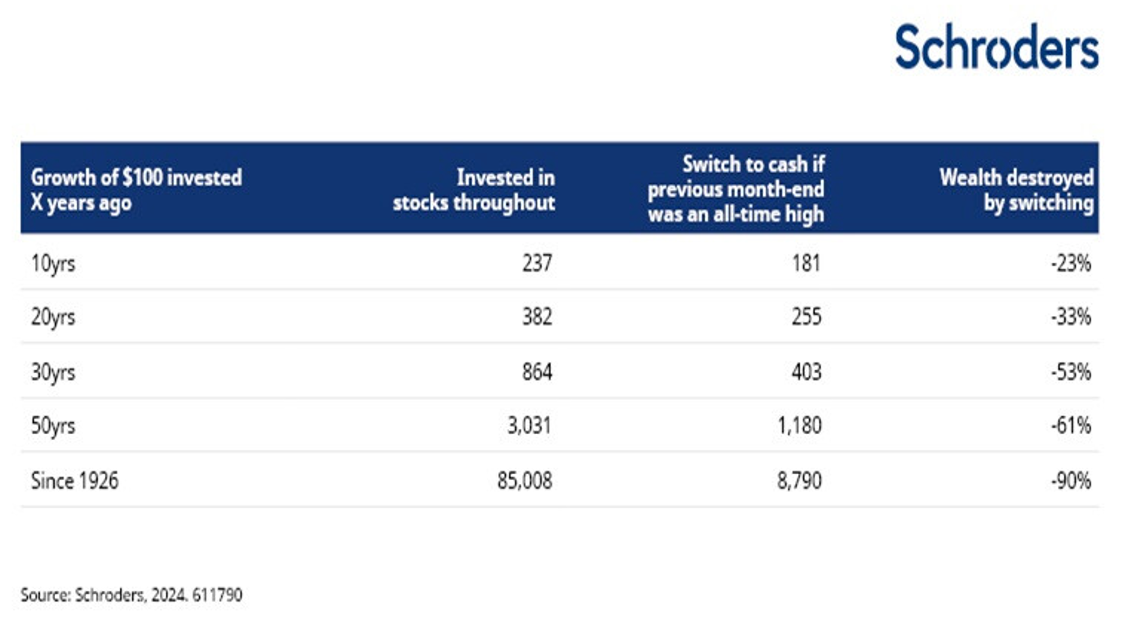

As Lamont notes, a $100 investment in the S&P 500 in 1926 would have been worth north of $85,000 at the end of last year on an inflation-adjusted basis. However, that same $100 would have been worth just $8,790 if the investor went to cash after a record was hit, went to cash and sat on the sidelines for a month.

In Bull Markets, Cash-Switching Is a Killer

Whether it’s a bull or bear market or something in between, market-timing is difficult and really not worth anyone’s time. On a related note, jitters at all-time highs are natural but should be quelled.

“It is normal to feel nervous about investing when the stock market is at an all-time high, but history suggests that giving in to that feeling would have been very damaging for your wealth. There may be valid reasons for you to dislike stocks. But the market being at an all-time high should not be one of them,” adds Lamont.

Think a cash-switching strategy at highs is worth it? Think again. Look at the chart below, courtesy of Schroders.

Related: