Institutional ‘forgetting’ is the single biggest constraint to decision-making excellence and a massive contributor to productivity shortfalls ~ Arnold Kransdorff

How do we get better at maintaining corporate memory? I have a log of my last 12 years of work stored as digital reminders in the form of photographs – and I look at them almost daily:

What was I working on 7 years ago?

Last year?

How much of it came to anything?

Why did we abandon that?

In truth the hit rate isn’t great: few things came to something truly impactful. Not as much as I’d like anyway.

I continue to do this most days , not out of some weird act of self-flagellation, but rather to enable me to prioritise the work I do today , and to never forget what didn’t work and why.

Recently, I’ve become prone to looking back and uncovering how many times we have tried to solve a problem before – and failed. If you work in a legacy organisation – one that existed before the modern internet – this should be standard practice. However, in my experience almost most no-one does this , so every time we attempt to solve a problem we start with a self imposed learning disability.

Doing this on something I was working on recently revealed we had attempted a new way to solve a new project approach to solve problem at least five times over the course of ten years. Each time we’d come up with a new way to solve it, but had never looked back at why it failed the last time. So we kept failing.

This is what is known as corporate amnesia or ‘institutional forgetting’ – a phenomenon where organizations lose valuable knowledge, experience, and insights over time. This can be a gradual process or a sudden occurrence, and it can have significant negative impacts on an organisation’s performance, decision-making, and innovation.

There’s some evidence suggesting that organisational memory might be getting shorter in certain contexts, the same argument that is levelled at at our attention span. There are several factors contributing to this phenomenon:

- Rapid Employee Turnover: In today’s fast-paced work environment, employees tend to change jobs more frequently. This can lead to a loss of institutional knowledge and experience when people leave, especially if knowledge transfer processes aren’t in place.

- Digital Transformation: The shift towards digital tools and platforms has led to a reliance on technology for storing information. While this can be beneficial, it also poses risks. If data isn’t managed properly or systems fail, valuable knowledge can be lost. Additionally, relying solely on digital records might neglect the importance of tacit knowledge (the “know-how” that isn’t so easily documented).

- Information Overload: The sheer volume of information available today can make it difficult for individuals and organisations to filter and retain what’s truly important. This can lead to a focus on the latest information at the expense of historical context and lessons learned.

- Globalization and Remote Work: As companies become more geographically dispersed and remote work becomes more common, it can be challenging to maintain a shared understanding and collective memory across different locations and time zones.

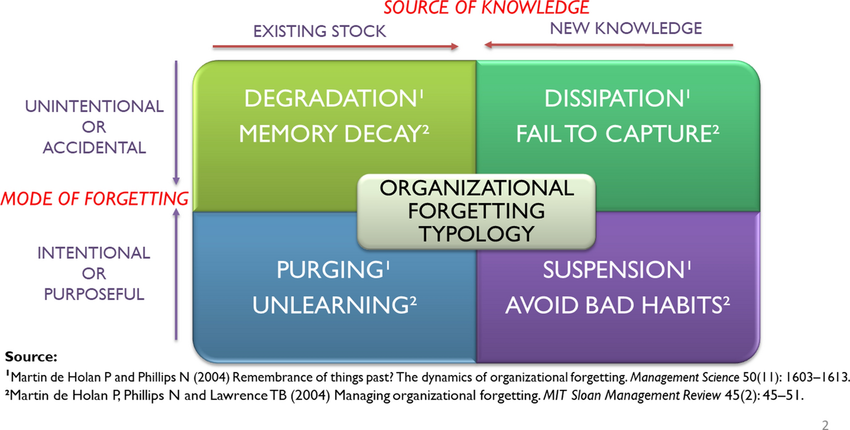

This is different from the deliberate purging of corporate memory through processes like unlearning. It’s as Holan and Phillips have laid out – when an organization accidentally loses the existing stock of knowledge through forgetting, degradation, or memory decay.

No one part of an organisation is susceptible to institutional forgetting than change programmes and change management. I bet I could show you a couple of proposed change pipelines with accompanying new governance arrangements for each year I’ve been logging work. It’s almost not worth learning the new one as another one will come along faster than you can say ‘kaizen’.

I say kaizen as it reminds me of a visit I made to Ricoh in 2015 after a recommendation from Chris Bolton. During the visit I commented to one our their improvement managers how impressed I was with their attempts to show a very visible ‘organisational memory’ with prompts all over the building. Seemingly their history, their people, their change and improvement approaches were embedded into almost every activity – from how a workbench was maintained to how someone parked a vehicle in a loading bay. I said it was inspirational.

The manager looked a bit sheepish at the compliment and replied graciously “It’s not perfect. We get it wrong sometimes” – before he added “but then , we’ve only been doing it for forty years.”

The idea of sticking at something for a year, never mind forty, is anathema to many western organisations

Many Japanese companies avoid corporate memory loss through a multi-faceted approach. They emphasise mentorship and apprenticeship, fostering knowledge sharing and collaboration among employees. Comprehensive documentation systems and knowledge repositories are used to store valuable information. Employee rotation and cross-functional teams promote a broader understanding of the organisation and prevent knowledge silos. Communities of practice encourage knowledge exchange among those with shared expertise. On-the-job training and lessons learned sessions ensure the transfer of both explicit and tacit knowledge, contributing to a continuous learning environment where institutional memory is preserved.

I’ve written before that you can learn a lot by looking at the oldest companies in the world, rather than fetishising the latest startups. One of the things that keeps these businesses going is that keep a strong corporate memory – they respect their tradition but aren’t afraid to change direction as needed.

In a world that glorifies the ‘move fast and break things’ mentality, it’s easy to forget the quiet wisdom accumulated over time. The Ricoh manager’s words, “we’ve only been doing it for forty years,” should resonate deeply. In our relentless pursuit of the new, we risk discarding the very knowledge we need to retain. Corporate memory isn’t just about preserving the past; it’s about arming ourselves with the insights needed to make smarter decisions, avoid repeating mistakes, and foster innovation.

True progress isn’t always about the next shiny thing, but about building upon the foundations of experience , wisdom and past failures.

Only then can we ensure that the work we do today has a lasting impact, rather than simply adding to an ever growing pile of forgotten initiatives.