Be afraid. Be very afraid.

That is how the media approached Covid. Be afraid of everything. Be afraid of being tall. Be afraid of being bald. Be afraid of going to the shops and accepting home deliveries.

The fearmongering is relentless. Be afraid of your pets. Be afraid for your pets. Just be afraid. ~ Laura Dodsworth

In August last year I went back to the office, the first time I’d been to a workplace since March. As I arrived I felt sick, even though I’d felt perfectly healthy just thirty minutes earlier. I recognised it for it was: anxiety, like the feeling of a first day at school. If I’m honest – I briefly considered cancelling. I wasn’t frightened of the virus, I was just frightened of people. I bit the bullet and walked inside..

As we emerge from a pandemic, in the UK at least, it’s necessary to reflect how changed we have become, and whether that change is permanent or temporary.

A study into Covid Anxiety Syndrome, characterised by fear of public places, compulsive hygiene habits, worrying about the virus and frequent symptom checking showed 46% of affected people feared returning to public transport, 44% feared touching things, while 35% were checking their family members and loved ones for signs of Covid on a regular basis.

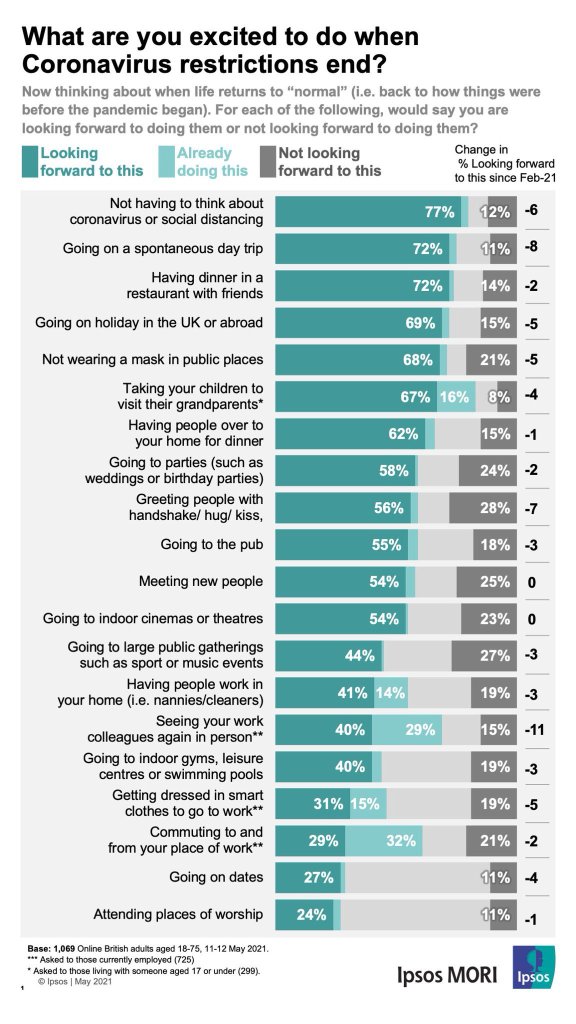

Polling from Ipsos MORI suggests it may be more than 20% of the general population that’s suffering from a form of Covid Anxiety Syndrome. It shows that 28% of British adults aren’t looking forward to “Greeting people with handshake/hug/kiss”, 27% aren’t looking forward to “going to large public gatherings such as sport of music events” and 24% aren’t looking forward to “Going to parties (such as weddings or birthday parties)”. 1 in 4 fear meeting new people.

I know of a fully vaccinated family friend who wants a hug from her fully vaccinated son more than anything. He won’t give it to her. More than half of Britons say they have not yet hugged a relative or close friend since restrictions on personal contact were eased,

Fear is a natural, powerful, and primitive emotion. It involves a biochemical response as well as a high individual emotional response. Fear alerts us to the presence of danger or the threat of harm, whether that danger is physical or psychological.

Marketeers have understand the unique value of fear for decades – it’s no surprise that the media has used the pandemic to sell more adverts.

However – sex sells and fear compels – and according to the new book by Laura Dodsworth, Covid has seen the Government use fear as a behavioural nudge on a mass scale.

Laura isn’t a Covid denier or even a lockdown sceptic, but has written about how tactics that sometimes wouldn’t pass the ethics board of a social experiment have become normalised.

In Options for Increasing Adherence To Social Distancing, the UK Government were advised on 22nd March 2020 that a substantial number of people “still do not feel sufficiently personally threatened by Covid; it could be that they are reassured by the low death rate in their demographic group” and in bold “The perceived level of personal threat needs to be increased among those who are complacent, using hard-hitting emotional messaging”.

Now, most of us would agree that in an emergency situation some degree of behavioural nudging , a science I’m actually a fan of, is necessary. The question that the book raises is the ethical question of how long this should continue, the tactics for ramping up unnecessary fear and the long term effect on society if anyone in authority becomes addicted to fear as a nudge.

Britain has been a world leader in behavioural insights since David Cameron set up the “nudge unit”. But has nudge become a shove? The book argues we went too far and that messaging that was initially designed to help us stay safe by scaring us has been so effective that we quickly became the most frightened nation in Europe, with people significantly over-estimating the spread and fatality rate of the disease. The British public think 6-7% of people have died from coronavirus – around one hundred times the actual death rate based on official figures.

I don’t go as far as Laura in her critique of behavioural insights as paternalistic. I think nudge can have a valid place in health , housing , justice and the social sector in general.

Where I’d agree with her is the ethical question about the overuse of fear as a motivator. It will be at least a couple of years before we can tell whether the cards were overplayed and understand the longer term impact.

Epidemics will come and go – but our basic psychology is here to stay.

I countered my fear by getting back in the office, and by having weekends away when I could. I went back to the gym and back to the pub on the day they reopened.

The best way to emerge from a state of fear is by being social, looking after friends and neighbours and being part of a community. The very things we were told to be afraid of are , ironically, the route out of this particular crisis.

Related: Why We Fail To Predict The Future