In the last few decades, as disclosure requirements for publicly traded firms have increased, annual reports and regulatory filings have become heftier. Some of this surge can be attributed to companies becoming more complex and geographically diversified, but much of it can be traced to increased disclosure requirements from accounting rule writers and market regulators. Driven by the belief that more disclosure is always better for investors, each market meltdown and corporate scandal has given rise to new reporting additions. In this post, I look at trends in corporate reporting and filings over time, and why well-meaning attempts to help investors have had the perverse effect of leaving them more confused and lost than ever before.

Time Trends in Reporting

Publicly traded firms have always had to report their results to their shareholders, but over time, the requirements on what they need to report, and how accessible those reports are to the public (including non-shareholders) has shifted. Until the early 1900s, reporting by public companies was meager, varied widely across firms, and depended largely on the whims of managers, with smaller, closely held firms among the most secretive. Between 1897 and 1905, for instance, Westinghouse Electric & Manufacturing neither published an annual report, not held a shareholder meeting. In the years before the First World War, the demands for more disclosure came from critics of big business, concerned about their market power, but few companies responded. It took the Great Depression for the New York Stock Exchange to wake up to the need for improved and standardized disclosure requirements, and for the government to create a regulatory body, the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). The SEC was created by the Securities Act of 1933, which was characterized as "an act to provide full and fair disclosure of the character of the securities sold in interstate and foreign commerce", and augmented by the Securities Exchange Act of 1934, covering secondary trading of securities. Almost in parallel, accounting as a profession found its footing and worked on creating rules that would apply to reporting, at least at publicly traded companies, with GAAP (Generally Accepted Accounting Principles) making its appearance in 1933. In the years since, disclosure requirements have changed and expanded, with companies in foreign markets creating their own rules in IFRS (International Financial Reporting Standards), with many commonalities and a few differences from GAAP. To get a measure of how disclosures have changed over time, I will focus on two filings that companies have been required to make with the SEC for decades. The first is the 10-K, an annual filing that all publicly traded companies have to make, in the United States. The second is the S-1, a prospectus that private companies planning to go public have to file, as a prelude to offering shares to public market investors.

The 10-K (Annual Filing)

The Securities Exchange Act of 1934 initiated the rule that companies of a certain size and number of shareholders have to file company information with the SEC both annually and quarterly. The threshold levels of company size and shareholder count have changed over time (it currently stands at $10 million in assets and 2000 shareholders), as have the information requirements for the filing. In the early years, the SEC summarized the company filings in reports to Congress, but the general public and investors had little access to the filings, relying instead on annual reports from the companies, for their information. It was the SEC's institution of an electronic filing system (EDGAR) in 1994 that has made both annual (10-K) and quarterly (10-Q) filings easily and more freely accessible to investors, leveling the playing field.

I valued my first company in 1981, using an annual report as the basis for financial data, but my usage of 10-Ks did not begin until the 1990s. I have always struggled with both the language and the length of these filings, but I must confess that these struggles have become worse over time. Put simply, there is less and less that I find useful in a 10-K filing, and more verbiage that seems more intended to confuse rather than inform. Let me start with how this filing has evolved at one company, Coca Cola, between 1994 and 2020, using the most simplistic metric that I can think of, i.e., the number of pages in the filing:

|

| Coca Cola Investor Relations |

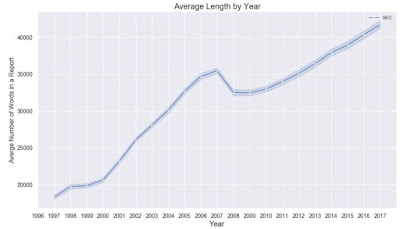

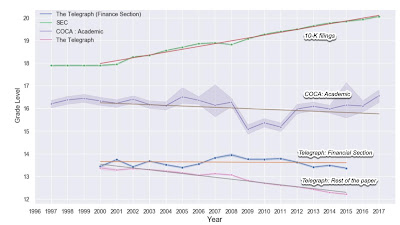

This is clearly anecdotal evidence, and may reflect company-specific factors, but there is evidence to indicate that Coca Cola is not alone in bulking up its SEC filings. In a research paper focused almost entirely on how 10-K disclosures have evolved over time, Dyers, Lang and Stice-Lawrence count not just the words in 10-K filings (one advantage of having electronic filings is that this gets easier), but also what they term redundant, boilerplate and sticky words (see descriptions below chart):

|

| Dyers, Lang and Stice-Lawrence

Redundant words: Number of words in sentence repeated verbatim in other portions of report

Boilerplate words: Words in sentences with 4-word phrases used in at least 75% of all firms' 10Ks

Sticky words: Words in sentences with 8-word phrase used in prior year's 10K

|

|

| Lesmy, Muchnik & Mugerman |

|

| Lesmy, Muchnik & Mugerman |

|

| Dyers, Lang and Stice-Lawrence |

|

| Dyers, Lang and Stice-Lawrence |

While the risk factor section may provide employment for lawyers, internal control for auditors and fair value/impairment for accountants, I have always found these sections to be, for the most part, useless, as an investor. The risk factors are legalese that state the obvious, the internal controls section (a special thanks to Sarbanes-Oxley for this add-on) is a self-assessment of management that they are "in control", and the fair value/impairment by accountants happens too late to be helpful to investors; by the time accountants get around to impairing or fairly valuing assets, the rest of the world has moved on.

The S-1 (Prospectus)

The S-1 is a prospectus filing that companies that plan to go public in the US have to make, and it plays multiple roles, a recording of the company’s financial history, a descriptor of its business models and risks and a planner for its offerings and proceeds. As with the 10-K, the requirements for the prospectus go back to the Securities Exchange Act of 1934, but the disclosure requirements have become more expansive over time. To provide a measure of how much the S-1 has bulked up over time, consider the table below, where I compare the number of pages in the prospectus filings of two high profile companies from each decade, from the 1980s to today:

|

| SEC Filings |

- The first is that the added verbiage on key inputs has made them more difficult to understand, rather than provide clarity. Consider, for instance, the disclosure requirements for share count, which have not changed substantially since the 1980s, but share structures have become more complex at companies, creating more confusion about shares outstanding. Airbnb, in its final prospectus, before its initial public offering asserted that there would 47.36 million class A and 490.89 million class B shares, after its offering, but then added that this share count excluded not only 30.87 million options on class A shares and 13.79 million options on class B shares, but also 37.51 million restricted stock units, subject to service and vesting requirements. While this is technically "disclosure", note that the key question of why restricted stock units are being ignored in share count is unanswered.

- The second is that companies have used the SEC's restrictions on making projections to their advantage, to tell big stories about value, while holding back details. For some companies, a key metric that is emphasized is the total addressable market (TAM), a critical number in determining value, but one that can be stretched to mean whatever you want it to, with little accountability built in. In 2019, Uber claimed that its TAM was $5.2 trillion, counting in all car sales and mass transit in that number, and Airbnb contended that its TAM was $3.4 trillion, five times larger than the entire hotel market's revenues in that year.

- Finally, while most companies, that are on the verge of going public, lose money and burn through cash, they have found creative ways of recomputing or adjusting earnings to make it look like they are making money. Thus, adding back stock-based compensation, capitalizing expenses that are designed to generate growth (like customer acquisition costs) and treating operating expenses as one-time or extraordinary, when they are neither, have become accepted practice.

In sum, prospectuses like 10-Ks have become bigger, more complex and less readable over time, and as with 10-Ks, investors find themselves more adrift than ever before, when trying to price initial public offerings.

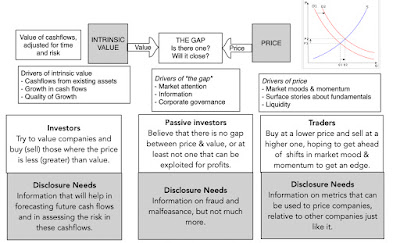

The Investor Perspective

As companies disclose more and more, investors should be becoming more informed and valuing/pricing companies should be getting easier, right? In my view, the answer is no, and I think that investors are being hurt by the relentless urge to add more disclosures. I am not the first, nor will I be the last one, arguing that the disclosure demon is out of control, but many of the arguments are framed in terms of the disclosure costs exceeding benefits, but these arguments cede the high ground to disclosure advocates, by accepting their premise that more disclosure is always good for investors and markets. On the contrary, I believe that the push for more disclosure is hurting investors and creating perverse consequences, for many reasons:

1. Information Overload: Is more disclosure always better than less? There are some who believe so, arguing that you always have the option of ignoring the disclosures that you don't want to use, and focusing on the disclosures that you do. Not surprisingly, their views on disclosure tend to be expansive, since as long as someone, somewhere, can find a use for disclosed data, it should be. The research accumulating on information overload suggests that they wrong, and that more data can lead to less rational and reasoned decision for three reasons. First, the human mind is easily distracted and as filings get longer and more rambling, it is easy to lose sight of the mission on hand and get lost on tangents. Second, as disclosures mount up on multiple dimensions, it is worth remembering that not all details matter equally. Put simply, sifting though the details that matter from the many data points that do not becomes more difficult, when you have 250 pages in a 10-K or S-1 filing. Third, behavioral research indicates that as people are inundated with more data, their minds often shut down and they revert back to "mental short cuts", simplistic decision making tools that throw out much or all of the data designed to help them on that decision. Is it any surprise that potential investors in an IPO price it based upon a user count or the size of the total accessible markets, choosing to ignore the tens of pages spent describing the risk profile or business structures of a company?

2. Feedback loop: As companies are increasingly required to disclose details about corporate governance and environmental practices in their filings, some of them have decided to use this as an excuse for adopting unfair rules and practices, and then disclosing them, operating on the precept that sins, once confessed, are forgiven.. This trend has been particularly true in corporate governance, where we have seen a surge in companies with shares with different voting rights and captive boards, since the advent of rules mandating corporate governance disclosure. For a particularly egregious example of overreach, with full disclosure, take a look at WeWork's prospectus and especially the rules that it explicitly laid out for CEO succession.

Much of the regulatory disclosure has been focused on what investors need to value companies, albeit often with an accounting bias. However, there are for more traders than investors in the market, and their information needs are often simpler and more basic than investors. Put simply, they want metrics that are uniformly estimated across companies and can be used in pricing, whether it be on revenues or earnings. With young companies, they may even prefer to use user or subscriber counts over any numbers on the financial statements.

4. Make it about the future, not just the past: While I don't think that anyone would dispute the contention that investing is always about the future, not the past, the regulatory disclosure rules in the US and elsewhere seem to ignore it. In fact, much of regulatory rule making is about forcing companies to reveal what has happened in their past, and while I would not take issue with that, I do take issue with the restrictions that disclosure laws put on forecasting the future. With the prospectus, for instance, I find it odd that companies are tightly constrained on what they can say about their future, but that they can wax eloquently about what has happened in the past. Given that much or all of the value of these companies comes from their future growth, what is the harm in allowing companies to be more explicit about their beliefs for the future? Is it possible that they will exaggerate their strengths and minimize their weaknesses? Of course, but investors know that already and can make their own corrections to these forecasts. More importantly, stopping companies from making these forecasts does not block others (analysts, market experts, sales people), often less scrupulous and less informed than the companies, from making their own forecasts.

5. Mission Confusion: Should disclosures be primarily directed at informing investors or protecting them? While it is easy to argue that you should do both, regulators have to decide which mission takes primacy, and from my perspective, it looks like protection is often given the lead position. Not surprisingly, it follows that disclosures become risk averse and lawyerly, and that companies follow templates that are designed to keep them on the straight and narrow, rather than ones that are more creative and focused on telling their business stories to investors.

Disclosure Fixes

The nature of dysfunctional processes is that they create vested interests that benefit from the dysfunction, and the disclosure process is no exception. I am under no illusions that what I am suggesting as guiding principles on disclosure will be quickly dismissed by the rule writers, but I am okay with that.

1. Less is more: I do think that most regulators and investors are aware that we are well past the point of diminishing returns on more disclosure, and that disclosures need slimming down. That is easier said than done, since it is far more difficult to pull back disclosure requirements than it is to add them. There are three suggestions that I would make, though there will be interest groups that will push back on each one. First, the risk profile, internal control and fair value/impairment sections need to be drastically reduced, and one way to prune is to ask investors (not accountants or lawyers) whether they find these disclosures useful. A more objective test of the value to investors of these disclosures is to look at the market price reaction to them, and if there is none, to assume that investors are not helped. (If you apply that test on goodwill impairment, you would not only save dozens of pages in disclosures, but also millions of dollars that are wasted every year on this absolutely useless exercise) Second, I would use a rule that has stood me in good stead, when trying to keep my clothes from overflowing my limited closet space, in the disclosure space. When a new disclosure is added, an old one of equivalent length has to be eliminated, which of course will set up a contest between competing needs, but that is healthy. Third, any disclosures that draw disproportionately on boilerplate language (risk sections are notorious for this) need to be shrunk or even eliminated.

2. Don't forget traders: Almost all of the disclosure, as written today, is focused on investor needs for information. Thus, there is almost no attention paid to the pricing metric being used in a sector, and to peer group comparisons. Rather than adopt a laissez fare approach, and let companies choose to provide these numbers, often on their own terms and with little oversight, it may make more sense that disclosure requirements on pricing and peer groups be more specific, allowing for different metrics in different sectors. Just to provide one illustration, I believe that the prospectus for a company aspiring to go public should include details of all past venture capital rounds, with imputed pricing in each round. While investors may not care much about this data, it is central for traders who are interested in pricing the company.

3. Let companies tell stories and make projections: The idea that allowing companies to make projections and fill in details about what they see in their future will lead to misleading and even fraudulent claims does not give potential buyers of its shares enough credit for being able to make their own judgments.With the S-1, the disclosure status quo is letting young companies off the hook, since they can provide the outlines of a story (TAM, multitude of users, growth in subscribers) without filling in the details that matter (market share, subscriber renewal and pricing).

4. With triggered disclosures: To the extent that some companies want to tell stories built around non-financial metrics like users, subscribers, customers or download, let them. That said, rather than requiring all companies to reveal unit economics data, given the misgivings we have about disclosures becoming denser and longer, we would argue for triggered disclosure, where any company that wants to build its story around its user or subscriber numbers (Uber, Netflix and Airbnb) will have to then provide full information about these users and subscribers (user acquisition costs, churn/renewal rates, cohort tables etc.)

I hope that we can keep these principles in mind, as we embark on what is now almost certain to become the next big disclosure debate, which is what companies should be required to report on environmental, social and governance (ESG) issues. You are probably aware of my dyspeptic views of the entire ESG phenomenon, and I am wary about the disclosure aspects as well. If we let ESG measurement services and consultants become the arbiters of what aspects of goodness and badness need to be measured and how, we are going to see disclosures become even more complex and lengthy than they already are. If you truly want companies to be good corporate citizens, you should fight to keep these disclosures in financial filings limited to only those ESG dimensions that are material, written in plain language (rather than in ESG buzzwords) and focused on specifics, rather than generalities. Speaking from the perspective of a teacher, put a word limit on these disclosures, take points off for obfuscation and then think of what existing disclosures should be removed to make room for it!

Related: Inflation and Investing: False Alarm or Fair Warning?