We are less pessimistic about our own lives than we are about larger units. We’re not very pessimistic about our village, we are not pessimistic about our town – but we are very pessimistic about our country, and even more pessimistic about the future of our planet. The bigger the unit you look at the more pessimistic people are about it. – Matt Ridley

Sometimes, the best way to get traction behind an idea or initiative is to make it as local as possible.

Your own community is the best unit of change. For instance, solving homelessness across the UK is a wicked problem that seems unsolvable. However, making sure no-one on your street is at risk of homelessness seems eminently achievable.

Some of this is just that our brains can’t easily comprehend how to solve massive problems. Counter-intuitively, the bigger the problem the less inclined we may be to help out.

That’s why charity appeals often feature a single distressed child (or animal) rather than featuring thousands. In one study to explore this the psychologist Paul Slovic told volunteers about a young girl suffering from starvation. He then measured how much the volunteers were willing to donate to help her. He presented another group of volunteers with the same story of the starving little girl — but this time, also told them about the millions of others suffering from starvation.

On a rational level, the volunteers in this second group should be just as likely to help the little girl, or even more likely because the statistics clearly established the seriousness of the problem. “What we found was just the opposite,” Slovic says. “People who were shown the statistics along with the information about the little girl gave about half as much money as those who just saw the little girl.”

In my last post I outlined three reasons we fail to solve problems, but there’s an important fourth one: sometimes we simply try and approach them in ways that are too hard to comprehend. We go way too big when we might be better off starting really small.

As Matt Ridley explains in this conversation with Jordan Peterson, optimism plays a hugely important role in innovation. And we are most optimistic about our own community – making it fertile ground for solving local problems.

One of the reasons that frugal – or jugaad – innovation thrives in parts of Asia is because it concentrates on local solutions, solved using simple means, with a spirit of eternal optimism.

Jugaad is a Hindi word that roughly means ‘solution born from cleverness.’ It’s usually applied to a low cost fix or work-around. In a culture where people often have to make do with what they have it’s an improvised or makeshift solution using scarce resources.

Anyone who has been to India or other parts of Asia will have seen examples of jugaad on a daily basis.

In case you’re new to the word I’ll give you four pictures, two of which I took myself in Cambodia.

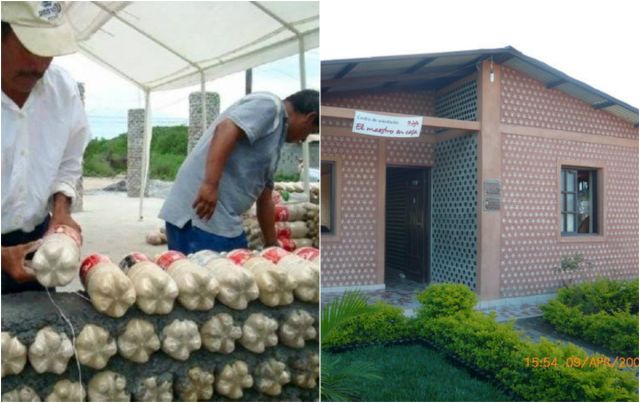

Building a house with discarded cola bottles:

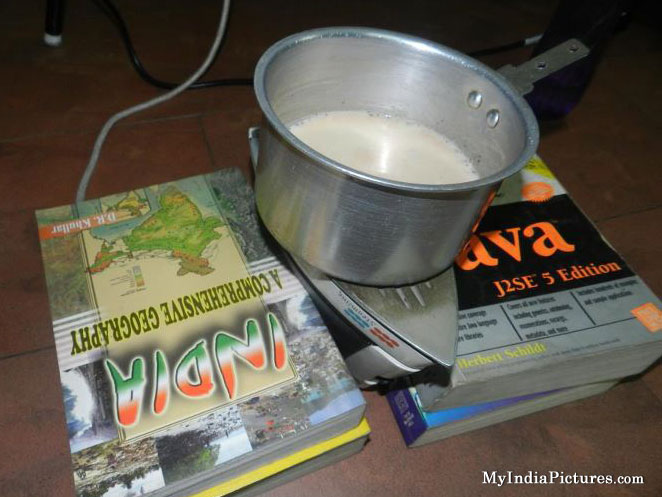

Making tea using an iron:

Attaching an extra seat onto mopeds (or attaching literally ANYTHING onto mopeds):

Bike + Tuk Tuk + Wifi:

Partly this is a result of austerity. In an era of abundance there isn’t much desire for the simple fix. Scarcity drives creativity in ways abundance cannot.

Frugal innovations are extremely context sensitive and it’s understood that local people are the ones best placed to understand their needs and address them – almost the opposite of how large scale change is managed in organisations.

Most organisational approaches to change or transformation are carefully structured. Agile or lean are process frameworks, whereas jugaad is void of process altogether.

My personal belief is the best way western organisations can adopt jugaad thinking is by directly channelling it into communities themselves. Any frugal revolution needs to be driven by people – not from your boardroom.

As an ex-colleague of mine William Lilley said a few years ago: Everyone has a story to tell, everyone has strengths beneath the conceptions that you have of them. But if you’re curious enough, you may just find that the answers you’ve always been looking for are there, often right beside you.

There is a massive untapped reservoir of skill and talent that we choose to ignore because we think we could do it better as professionals.

It could be that a lot of our problems are sitting there waiting to be solved by our colleagues and communities.

We just need to give them permission, and get out of the way.