At the epicenter of the US/China trade war that intensified under the Trump Administration is a disinclined semiconductor industry. The ongoing flap puts both countries' chip industries in tough positions with China likely to feel increasing near-term pressure.

On the technology front, some of the most glaring headlines emanating from the fractured relationship from the world's two largest economies include the blacklisting of telecom gear maker Huawei, which has substantial chip needs, and the 2019 decision of Semiconductor Manufacturing International (SMIC) to delist from the New York Stock Exchange. SMIC, China's largest chip maker, traded over- the-counter in the U.S. for nearly two years before the Trump Administration last November barred American investment in companies identified as “affiliated with the Chinese military.”

Those hostilities are palpable particularly when considering China imports about $300 billion worth of chips per year and most of the major domestic semiconductor companies depend on Chinese clients for a quarter of sales or more, according to the Brookings Institution.

“In a post-COVID, post-Trump world, many in Washington would like to see the American economy less dependent on China and are exploring new restrictions on imports of Chinese hardware and exports of both cutting-edge semiconductors and the equipment required to manufacture them,” notes the think tank.

China Has Ambitions, But It's Lagging

The trade imbroglio with the U.S. is all the impetus China needs to become less dependent on technology imports. Beijing hopes that by 2025, 70 percent of the country's chip needs will be met by domestically produced goods. The goal was to get 40 percent in 2020, up from just 16 percent in 2019.

An ambitious effort to be sure, but China has a problem and it speaks to its dependence on imported chips – namely of the U.S. variety. Currently, the chips being manufactured in China are at least two generations behind those being produced at Taiwan Semiconductor (TSMC) foundries.

Excluding vertically integrated Intel, TSM's client roster includes venerable names such as Advanced Micro Devices, Apple, Nvidia and Qualcomm, among others. TSMC is a vital variable in the semiconductor conversation. For the most part, the company was able to appease both China and the U.S. and not run afoul of either, but that plan may not be tenable on a long-term basis.

“TSMC has announced that it will build a new factory in Arizona as it faces Chinese firms poaching its employees and Chinese actors hacking its systems and code for trade secrets—all actions demonstrating how great power competition will play out for tech dominance,” according to the Foreign Policy Research Institute (FPRI). “Avoiding direct live-fire conflict, China and the United States will work to restrict the other’s actions and development by forcing important tech companies, such as TSMC, into picking a side.”

Independence: A Moving Target

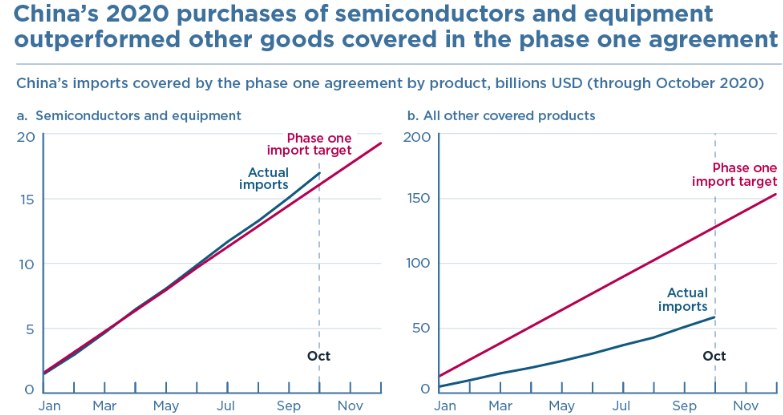

China's plans to curb technology imports are admirable, but the goal is long-ranging at best. The trade agreement with the U.S. confirms as much. As the chart below indicates, China's purchases of other goods under Phase One of the accord increased, but were well below targets. Conversely, the country's imports of U.S. chips and related equipment are on pace to meet or exceeds terms of the pact.

That's one indication China's goal of attaining chip independence is perhaps rooted more in ambition than reality. The other sign China is up against it when it comes to curb semiconductor imports is sheer math.

According to Brookings, there are at least 20 different chip categories each with at least 300 inputs. That's an astronomical amount of potential combinations and it confirms why no country is truly chip “independent.”

Going forward, China will undoubtedly continue its quest for manufacturing close to or all of its needed semiconductor, but it's also possible it finds the deck is stacked against it in that endeavor.

Related: Five 2021 Technology Predictions