Will Tariffs Restore Manufacturing Jobs? University of Arizona Economic Historian, Price Fishback, Provides the Facts

Price Fishback is a distinguished professor of economics at the University of Arizona and a Research Associate at the National Bureau of Economic Research. He’s also an expert on American economic history, particularly the course of employment and output over the past two centuries. I asked Price to tell me about the successful postwar use of tariffs to surge jobs in the steel industry. Turns out there’s no such history. Let me paraphrase what I learned from Price.

'Today’s high-income nations have experienced long-term output and employment transitions in both agriculture and manufacturing — with dramatic sectoral increases in output accompanied by dramatic sectoral declines in employment.

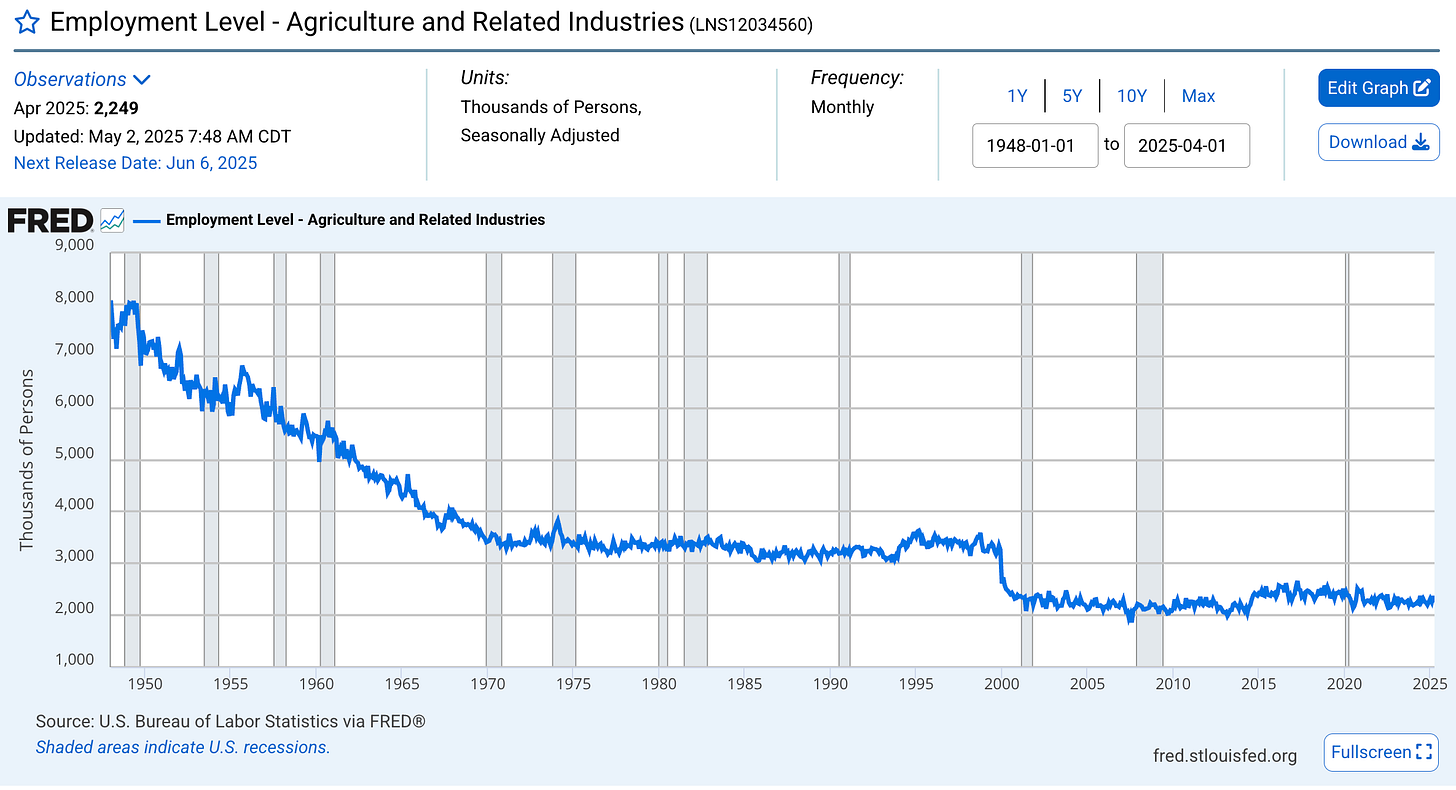

Postwar growth in U.S. agricultural output provides a prime example. Farm output more than tripled since 1947 while the number of farmers fell by 6 million — a whopping three quarters!

This is an old story. It’s not a story about imports, cheap foreign labor, trade deficits, or America getting a raw deal. It’s a story about automation. In the early 1800s, 85 percent of the labor force worked on farms, feeding 5 million people. Fast forward a century when the number of farmers peaked at 11 million. Although farmers had more than doubled, the population had grown much faster. Consequently, farmers comprised less than one third of workers. Although, Americans had largely left the farm, the ones who stayed produced enough food to sustain five times their number. Today, agriculture employs less than 2 million Americans. But those 2 million farmers, aided by their enormously productive and smart machines, not only feed our population of 340 million, but also to ship vast quantities of food abroad.

Postwar American manufacturing is agriculture redux. Real value added in manufacturing has risen tenfold. But manufacturing employment, which rose from 13 million in 1950 to 19 million in 1979, is now below 13 million. Meanwhile, the workforce has grown — a lot! Consequently, today’s manufacturing’s share of employment is just 8 percent, down from 25 percent 75 years ago.

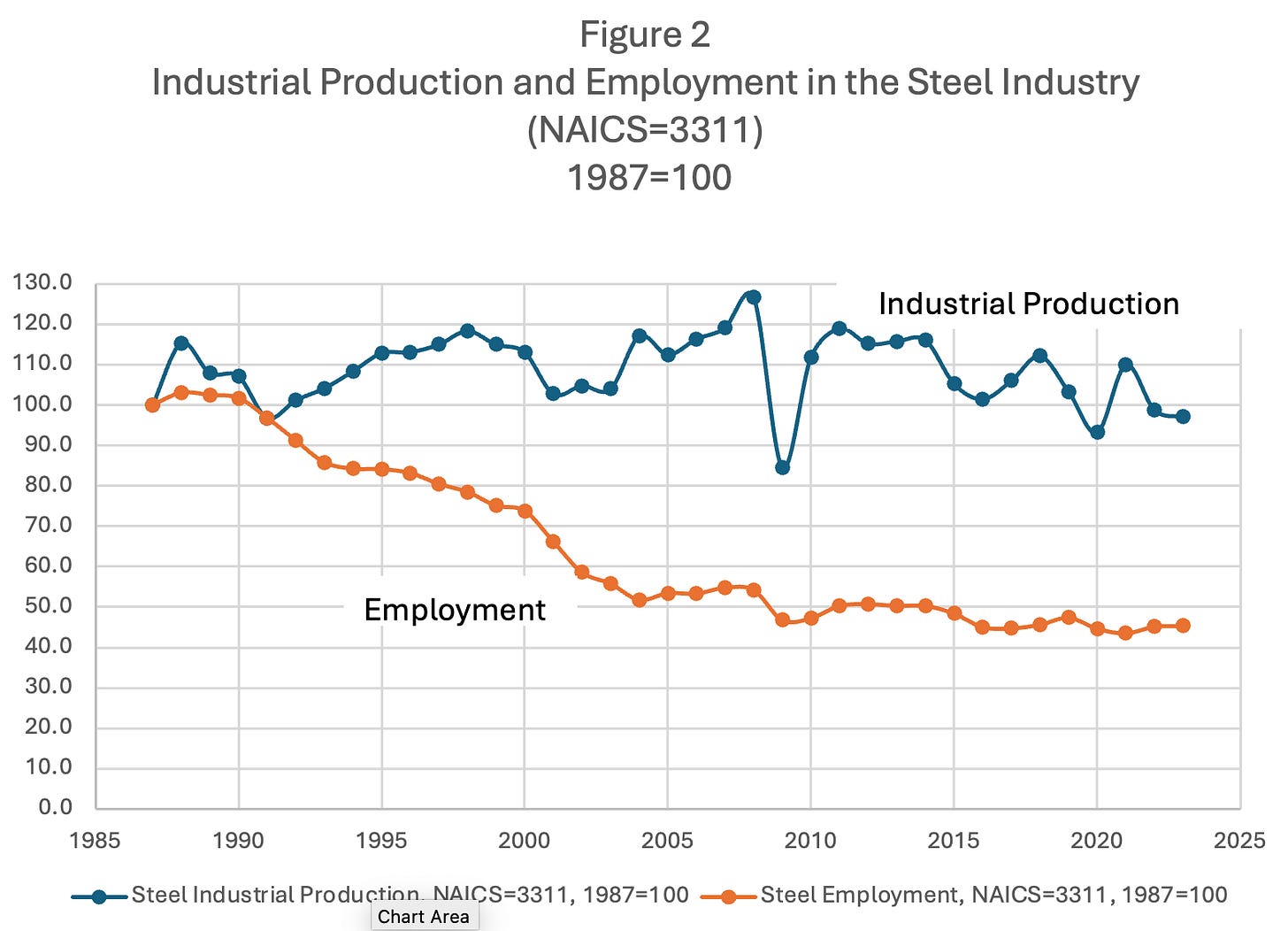

Would higher tariffs have saved manufacturing? The steel industry provides a telling case study. The steel industry has been highly successful, decade after decade, in securing trade protection. The U.S. negotiated voluntary steel-export restrictions with the Europeans and the Japanese on multiple occasions. We also set, in 1977, minimum trigger prices to limit imports. And we filed dozens of anti-dumping claims with international courts. President George H.W. Bush extended the voluntary restrictions and began multi-lateral steel negotiations during his administration. From 2002 through 2005, President George W. Bush established steel tariffs ranging from 8 to 30 percent. President Trump imposed additional steel duties in his first term and just set steel and aluminum duties at 25 percent.

Despite the industry’s protection, total U.S. steel production fell from a peak of 146 million tons in 1974 to 98 million tons in 1989. Employment fell by an even larger percentage — almost half, with the number of steel workers plummeting from over 500,000 to just 236,000. The bottom figure picks up the story from 1987. Steel production has bounced around since then. But its currently close to its 1987 level. Meanwhile, steel employment has dropped by more than half. It fell particularly sharply during the 2002-2005 period — when the Bush steel tariff was in place. As in manufacturing, the steel industry has survived by substituting technologically-endowed capital, aka smart machines, for labor, i.e., by sharply raising output per worker.

In manufacturing, in general, and steel, in particular, smart machines have outmoded people. With or with tariff protection, manufacturing workers have gone the way of the horse. Horses, at the start of the last century, numbered 50 million. The gasoline engine ended their careers. Today, only 3 million horses grace our country and virtually all are literally out to pasture. Fortunately, U.S. manufacturing workers had and have alternatives. Job opportunities in services and other sectors have expanded to keep the nation’s employment rate high despite annumber of job seekers.

Manufacturing is now the purview of emerging nations. Yet, “Made in America” may stage a comeback. But it will be one with highly automated plants with nary a flesh and blood creature to be seen. After all, a fully automated factory with maintenance robots can operate equally well anywhere in the world.

Economic history is clear. Fighting comparative advantage is like fighting city hall. It can’t be done. It’s hopeless without tariffs and it’s hopeless with tariffs. But the real job killer has nothing fundamentally to do with international trade. It’s the machines, with their ever growing AI brains, that have been and are coming for our jobs. They were coming well before China took its great capitalistic leap forward. And they will be coming, at an accelerating pace, for every remaining job, including every job in China.

Long term, the question is not who will produce what. Long term, smart machines will produce everything, including themselves. The real questions are these. Will smart machines control us or will we control them? And, if we control them, who will own them — a handful of oligarchs living on a gated island or humanity at large? So far it looks like the oligarchs will own as well as rule the roost

Ah, but there’s the rub. As wealth becomes fully concentrated and production becomes fully automated, who will demand (be able to buy) the products the smart machines produce? As this dismal economics paper envisions, demand (well, lack of demand) kills its own supply, reversing the old economics maxim (Say’s Law) that supply creates its own demand. The President and his appointees might stop foaming at the mouth about trade deficits and consider what’s really going on.'

Related: The Economist Who Knows Putin Best: Anders Åslund on America's Strategic Failures