Even if your customer satisfaction scores are upper quartile, even if you’re a favourite with your regulator, that crisis can be waiting just around the corner for any organisation.

In 2014 General Motors began the recall of the Chevrolet Cobalt which would ultimately affect nearly 30 million cars worldwide.

The problem was with the ignition switch which could shut off the car while it was being driven, disabling power steering, power brakes – and, crucially, the airbag.

The issue had been known to GM employees for a decade. A sixteen-year-old girl had died in a frontal crash in 2005, the first death attributed to the defective switches.

A redesign of the ignition switch went into vehicles a year later, but a simple mistake was made – the engineers failed to alter the serial number – which made the change difficult to track later.

Ultimately the flaw would kill 124 people, and seriously injure 275 others. Not recalling the vehicles sooner was deemed affordable in the pursuit of profit.

During this time, General Motors was leading its sector in customer satisfaction. At the same time as their cars were devastating families, they were picking up heaps of industry awards.

It’s common after the emergence of any scandal, be it VW, Oxfam, Mid Staffordshire, and now the UK Post Office for us to call for tighter regulation, greater consumer controls, and increased transparency of performance.

But does any of this help prevent complex system failure?

When Good Companies Go Bad

It’s tempting to think that tighter regulation and scrutiny prevents system failure but there’s little actual evidence it does.

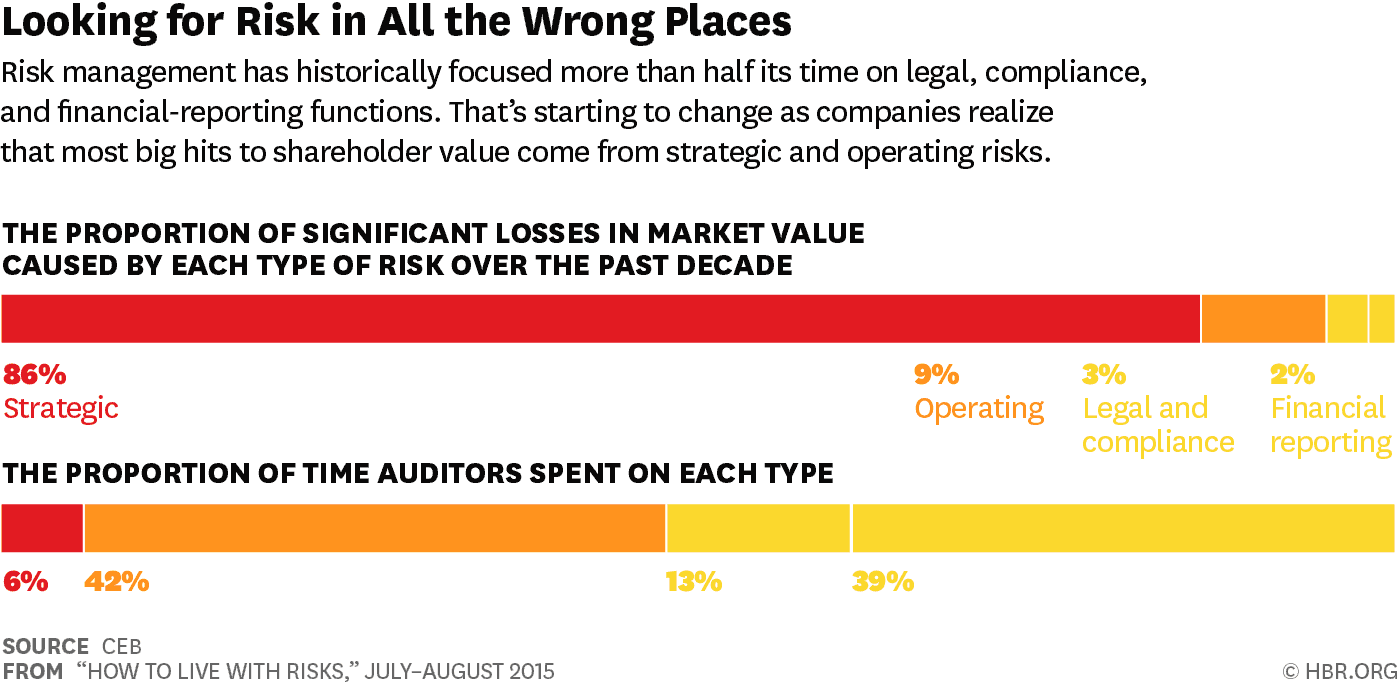

There’s a problem with managing risk retrospectively: you’re always looking behind you, and often looking in the wrong places.

When things go wrong in organisations it’s often the result of a complex web of perverse incentives, simple mistakes and a culture of people looking the other way.

It’s almost never because there’s a singular manager saying “I’m going to do this on the cheap even though it’s bad for customers and might kill folk”.

Learn From The Deviants

I was considering this when a post popped into my inbox from Bob Marshall (AKA FlowchainSensei), in which he reminds us of the importance of learning from positive deviant organisations.

“Positive deviant organisations thrive by bucking industry trends and norms. And by founding their principles and practices in radically different collective assumptions and beliefs they develop unique practices, processes and cultures that allow them to achieve exceptional results. Studying how these maverick organisations operate can provide valuable insights for leaders looking to foster innovation.”

In his book “Quintessence” Bob cites the Morning Star Company as an example of corporate positive deviance. Morning Star have the kind of radically different principles that no regulator or consumer standard would recognise as normality:

From The Corporate Rebels: “With no bosses, no titles and no structural hierarchy, Morning Star’s prime principle is that all interactions should be voluntary. Each colleague enters the enterprise with the same set of rights as any other colleague. Not a single colleague can force another colleague to do something they don’t want to do.“

Positive deviance could be attractive to non-profit or community organisations as it is participatory, and a relatively low cost way of achieving change.

How do you build on deviant behaviour?

In 1990, an American couple named Jerry and Monique Sternin were sent by Save the Children to fight severe malnutrition in the rural communities of Vietnam. Tired of ‘do gooder’ approaches that had cost lots and delivered little the Vietnamese Foreign Minister gave them just 6 months to make an impact.

When you’ve got weeks rather than years to solve a problem, and children are literally dying before you, you don’t have time for the theatre of change management. Equally you can’t lose yourself in the complex systemic causes of poverty.

Instead the Sternins decided to build upon what was already there – rather than parachute in new solutions. So they travelled to various villages and sought out the real experts: the mothers. They asked these mothers to help identify the villagers whose babies were bigger and healthier than the others.

In every community, organisation, or social group, there are certain individuals or groups whose behaviours and strategies enable them to find better solutions to problems than their peers, while having access to exactly the same resources.

Sternin later termed these people “positive deviants” – those who have – without realising it – discovered the path to success for the entire group.

- Positive – in that they are doing something that achieves a fundamentally good outcome.

- Deviant – in that their methods are not normal or universally understood or accepted. They may even be frowned upon or distrusted.

The Sternins found that the mothers of the healthiest children were indeed doing things differently.

- They were were feeding their children smaller portions of food rather than larger portions – but they were feeding them more frequently.

- They were taking ‘low class’ food – like brine shrimp from the paddy fields – that was stigmatized by others and adding these to their daily soups or rice dishes.

- They were ignoring the socially acceptable norm to feed family elders first – and serving their kids from the bottom of the pot, making sure the kids got the most nutritious food that had settled during cooking.

Alleviating the problem didn’t require huge resources – it simply required connecting other community members with these ‘positive deviants’ and encouraging them to start emulating their behaviour.

Building an organisation based upon positive deviance is likely to be criticised, or mocked.

The crisis that has engulfed the UK Post Office is an example of negative deviant workplace behaviours – those that violate organisational norms, policies or internal rules. According to the Guardian the “main driver was seemingly a toxic and secretive management culture with the victims marginalised, dismissed and disbelieved.”

Positive deviant workplace behaviours are the opposite – those that honorably violate industry norms or best practices.

In the most recent survey by YouGov the Post Office was the most trusted delivery brand, but conventional wisdom almost always lags reality.

I’m pretty sure General Motors, VW, and Oxfam would have been near the top of any industry league table too.

You can’t regulate a toxic culture and you don’t build trust with a consumer standard. If you really want to know what’s going on in an organisation you need to look in the places they don’t want you to.

And if you want to be an exceptional organisation that others look to and think “how do they do that?” , you have to be a positive deviant.