This headline caught my attention the other day:

Bank loyalty costs savers £1.6 billion a year in missed interest

The detail:

There’s £246.5 billion ($340 billion) languishing in accounts paying no interest at all …

A survey of 2,000 adults across the UK, with 42 percent of respondents stating that they didn’t think it was worth the bother with interest rates being so low across the board. The second most common reason for savers not switching accounts was because they said they trusted their bank and did not want to leave (24 percent), followed by 17 percent considering a switch ‘too much hassle’. Overall fewer than a third of people have switched accounts in the past 12 months (31 percent), while half haven’t switched for five years or longer and the same percentage have never switched at all. Women are less likely to have switched than men (40 percent have never switched compared with 33 percent of men).

So, it made me think. £246 billion in the UK is equivalent to almost fifteen percent of UK GDP (£2 trillion, $2.8 trillion, in 2019). If that’s the case, and if you take global numbers, then around $12-$13 trillion of global GDP ($85 trillion in 2019) is sitting, gathering dust. Of that number, it also means that $72 billion is being wasted and lost in interest each year, on that $12 trillion number.

$72 billion a year because people cannot be bothered.

The question then should be: who gets the $72 billion?

What about dormant accounts?

People die, move or just plain forget they have an account. UK Government estimated in 2018 that the value of those dead accounts would be worth £330 million ($456 billion). They define a dead account as one that has not had any transactions in the last 15 years but, if that’s the case, there’s probably a lot more out there. Then, zoom out to get a world view, and there’s likely to be a further $10 billion of dead money out there.

Bearing in mind this is consumer funds, what about the rest?

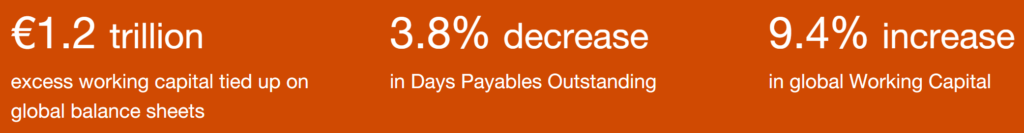

I talked about working capital losses years ago when, back in 2018, it was estimaged that over a trillion dollars globally was locked up in wasted structures.

Source: PwC

For those unfamiliar, working capital is all about the efficiency of money in and money out in business. Days outstanding is the time waiting for a payment. The longer it takes a business to received a payment, the more the business strains its’ efficiency. The fast a payment comes through, the better a business performs.

There are ways around this – there’s a whole business focused upon the process called factoring – but business efficiency is severely affected by the speed of payments from customers and to suppliers.

The inefficiency estimate by PwC is €1.2 trillion. I’ve seen others who estimate it to be five times this amount. So, for the purposes of this blog, let’s call it $2 trillion a year that languishes between accounts due to inefficiencies.

Add the retail figures of $72 billion of lost interest to this and $10 billon of dead accounts, and we are talking a lot of money gathering dust around the world. My guess is that it’s a minimum of $1.5 trillion and a maximum of $6 trillion. That’s quite a range. Let’s be conservative and take the lower range. Let’s say that $2 trillion a year sits in bank accounts, languishing and rotting.

What happens to these trillions of dollars?

Well, it makes the bank money in leverage and interest. No wonder so many people want to create a bank.