Written by: Kate Maier

Estate planning can be a taxing (pun intended) part of creating a comprehensive financial plan. You worked hard to accumulate your wealth, and you want to pass as much of it as possible to your beneficiaries. However, if you are lucky enough to have a large estate, you may be required to pay considerable estate and gift taxes when you pass your assets to your heirs.

Fortunately, there are ways to potentially reduce the amount you owe in taxes, one of which being a grantor-retained annuity trust (GRAT). To understand what a GRAT is, its benefits for estate planning, and how it may provide substantial tax savings, read on.

Take the first step towards financial well-being. Click here to schedule your free consultation with our experienced advisors.

What Is a Grantor-Retained Annuity Trust?

Since they’re such a large component of GRATs, it helps to first discuss annuities. At a high level, annuities are financial contracts that pay out a steady stream of income over time. In essence, you contribute funds or assets (like shares or options) into an account, and in exchange the account distributes regular payments in equal instalments either immediately or at some point in the future. This predictable income makes annuities popular for retirement and other long-term financial planning, as they provide financial stability over time.

In the context of a grantor-retained annuity trust, the annuity represents payments that go back to the “grantor”—the person who set up the trust. That means that when you retain the annuities from the trust, those payments distribute back to you.

Typically, the payments are a set percentage of the original amount in the trust. For example, if you set up a GRAT with $100,000 and a fixed annuity of 6%, you would receive $6,000 every year, regardless of how much is left in the trust. The exception is if the value of the trust drops below the annuity payment amount. In that case, the annuity payment will be what is left of the trust assets, and no further payment will be made from the trust. Unlike an annuity offered by an insurance company, if the trust runs out of money, no further annuity payments are made.

How Does a GRAT Work?

For estate planning purposes, a GRAT is a type of gifting trust that allows individuals to transfer high-yielding and/or rapidly appreciating property or assets (such as stocks or real estate) to a beneficiary with minimal gift or estate tax. Here’s how it works:

The grantor sets up an irrevocable trust and transfers assets to the GRAT. This transfer initiates a defined term, commonly between two and 10 years, during which the grantor receives fixed annual annuity payments. These payments are typically calculated based on the total initial value of the assets and the IRS’s assumed growth rate (called the “§7520 rate” from Section 7520 of the Internal Revenue Code).

Throughout the term, the trust assets ideally grow at a rate higher than this IRS-set rate.¹ As the assets appreciate, the grantor receives the scheduled annuity payments. Then, at the end of the GRAT term, any remaining funds, including any appreciation on the assets, are distributed to the trust’s beneficiaries. If the assets have appreciated above the IRS-assumed rate, this appreciation passes to the beneficiaries free of gift tax.

This tax-free transfer happens because of a nuance in the rules that lets you determine the gift tax at the time the GRAT is created by subtracting the grantor’s retained interest in the trust (i.e., the totality of the annuity payments) from the fair market value of the assets gifted to the trust. The fair market value is determined at the time you transfer the assets to the trust and is then “frozen”—effectively removing additional appreciation from your estate and passing it along to your beneficiaries.

Since the gift tax amount is determined when the trust is created, the value of the annuity interest ends up being a theoretical or projected figure. So, if you set your annuity to pay out the entirety of the principal value over the term of the trust, plus the assumed appreciation according to the §7520 rate, you effectively “zero out” the trust remainder, meaning you would owe nothing in gift taxes.

Types of GRATs

There are a few different types of GRATs, each designed to accommodate different estate planning needs.

- Standard GRATs are straightforward single-term trusts that last for a predetermined number of years. During this period, the grantor receives annual annuity payments. Once the term concludes, any remaining assets pass to the beneficiaries, free of additional gift tax on appreciation.

- Rolling GRATs are a series of shorter-term GRATs that capitalize on asset growth in intervals. With rolling GRATs, the grantor uses assets returned from each annuity payment to fund new GRATs as each term ends. This strategy may offer greater flexibility and increased potential to capture appreciation, as it involves re-valuating assets more frequently based on prevailing market conditions.

- Zeroed-Out GRATs take advantage of the gift tax exemption by setting the annuity payments so that the present value of the remainder interest—the portion left for beneficiaries—is close to zero. This means the gift tax calculated at the time of the trust’s creation is minimal or non-existent. With this approach, any asset appreciation transfers to beneficiaries tax-free, making it an attractive way to maximize tax efficiency.

How Are GRATs Taxed?

GRATs are subject to both income and gift taxes. Any income you earn from the appreciation of your assets in the trust is subject to regular income tax. This can be helpful to your beneficiaries, as it allows the trust’s assets to grow without depleting funds for income tax payments. For grantors with significant wealth, the income tax is generally a manageable cost, positioning you to optimize the assets that ultimately transfer to your beneficiaries.

On the flip side, when you establish a GRAT, you effectively make a gift to the trust beneficiaries. This means any remaining funds or assets that transfer to beneficiaries are subject to gift taxes. As we already noted, however, the value of that gift is typically reduced by the annuity payments you take during the trust term. In zeroed-out GRATs, the annuity is structured to fully offset the gift’s value, often resulting in minimal or zero taxable gift value at the time of creation.

Because GRATs are typically populated with high-yield assets, over the trust’s term it’s expected (or at least hoped) that those assets will appreciate significantly in value to something greater than the value of the projected growth rate, based on the federal tables. Essentially, when you set up your annuity payment schedule, your goal is to get the entire original trust value paid back to you in an annuity, leaving the appreciation to transfer to your beneficiaries without incurring any gift tax.

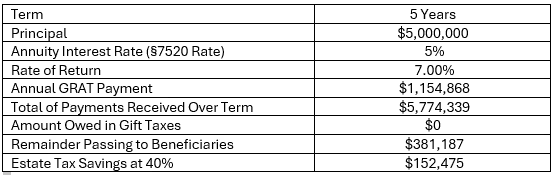

Figure 1. GRAT Example

In Figure 1 above, the grantor avoided paying gift taxes altogether while also leaving nearly $400,000 for their beneficiaries. Meanwhile, if that same dollar amount had passed down to their heirs at their time of death, that gift would be subject to the current 40% federal estate tax,² meaning their beneficiaries would have only received $ 228,712. The upshot? By using a GRAT, this person saved nearly $152,475 in taxes.

Pros and Cons of a GRAT

Like any estate planning tool, GRATs come with advantages and drawbacks.

Pros

There are several benefits to setting up a GRAT. For one, the trust pays out an annuity every year, which can work as part of your retirement income strategy. Similarly, you have flexibility to select a term length that suits your needs. While GRAT terms are typically between two and 10 years, you could arguably set up a GRAT with an even longer term (e.g., 20 years) to give the assets in the GRAT more time to appreciate. Transferring assets to a GRAT can also help reduce the size of your taxable estate, potentially minimizing estate taxes.

However, the main benefit of establishing a GRAT is the potential to transfer large amounts of money to a beneficiary while paying little to no gift tax. Annual gifting is an important part of estate planning, since it allows you to transfer assets to a beneficiary without reducing what you can give tax-free at death—as long as that gift does not exceed the federal annual exclusion amount. That exemption is $18,000 for 2024 and $19,000 for 2025. This means you can make annual gifts up to these amounts without utilizing your lifetime exemption.

By using a GRAT as part of your estate planning strategy, it’s possible to transfer much more than $18,000 (or $19,000) to a beneficiary without reducing your exemption. Again, this is a huge benefit for wealthier individuals with large estates. It allows them to transfer more valuable assets or properties in a shorter amount of time and potentially avoid or significantly reduce the gift and estate tax liability that such a sizable transfer would typically incur.

Cons

Despite these benefits, GRATs are not without drawbacks. One major consideration is the mortality risk. When a GRAT is created, you also set the term, or lifetime, of the trust. Once the term expires, the remaining assets transfer to your beneficiaries. However, if you pass away before the term expires, then all assets in the trust revert to your estate, effectively negating the anticipated tax savings.

That’s why setting the term can be a bit challenging. Longer terms allow more time for your assets to appreciate, and yielding a high capital gain is the main driver behind establishing a GRAT in the first place. However, the longer term you set—for example, 20 years—the higher the mortality risk.

Additionally, since you typically only avoid gift tax on asset appreciation, it makes sense to only populate your GRATs with high-yielding assets like stock, and/or to create the GRATs when interest rates are low. If you’re not seeing significant appreciation with these assets, or if the §7520 rate requires high appreciation in your assets to pass that appreciation to your heirs, it may be simpler to gift these funds or assets through more traditional means.

Lastly, gifted assets retain the cost basis you hold in the assets. This means that when your beneficiaries eventually sell the asset, they will have to pay capital gains taxes on the full gain associated with the property—not just the gain they realized from the time they received the asset. Your beneficiaries may consequently end up having to pay significant taxes on the gifted property.

That said, long-term capital gains tax (a maximum of 20% paid only on the appreciation of the assets) will still likely be lower than the estate tax you would owe (a maximum of 40% on the entire amount exceeding the estate exemption).

The Bottom Line

Adding a grantor-retained annuity trust to your estate plan can provide you with a strategic way to transfer wealth to future generations without the typical tax burden associated with large gifts. If you have highly appreciable assets and clear estate planning goals, a GRAT can be a valuable way to leave a significant legacy.

However, GRATs are not right for everyone. Setting up a GRAT requires careful planning and professional guidance to make sure they comply with complex legal regulations and are optimally structured.

If you would like to explore whether a grantor-retained annuity trust might fit into your estate plan, reach out to your financial advisor today.

Frequently Asked Questions

Who pays income tax on a GRAT?

The grantor pays the income tax on any earnings generated by the GRAT during its term. This allows the trust’s assets to grow without being depleted by income taxes, ideally optimizing the eventual transfer to beneficiaries.

What assets can you put into a GRAT?

GRATs typically hold assets with high appreciation potential, such as stock, real estate, or private business interests. Assets that are likely to grow beyond the IRS-assumed rate optimize the benefits a GRAT offers.

What happens to a GRAT when the grantor dies?

If the grantor passes away before the end of the trust term, the assets remaining in the GRAT revert to the grantor’s estate, generally forfeiting the anticipated tax benefits.

Can you modify a GRAT once it’s set up?

Once established, a GRAT is irrevocable, meaning it cannot be modified or canceled. This makes careful planning essential before its creation.

How long should a GRAT term be?

The term length for a GRAT is flexible but generally ranges from two to 10 years. A shorter term might be used in a rolling GRAT strategy, while longer terms may apply to single-term GRATs. The longer the term, the more time the GRAT’s assets have to appreciate. On the flip side, a longer term introduces a higher mortality risk.

¹Under IRS rules, the §7520 rate is equal to 120% of the Applicable Federal Annual Midterm Rate for the month that the assets are transferred to the trust.

²Gift tax is typically owed only on amounts that exceed the allotted lifetime gift exclusion, which is $13.61 million in 2024 and $13.99 million in 2025.

Related: Women’s Sports Leagues Break Revenue Records: A Slam Dunk for Investors