Imagine if someone asked you how hot it was in America last month. How would you respond to such a vague question? As everyone knows, temperatures vary greatly depending on a number of factors, from region to elevation, from time of year to even time of day.

Is the person inquiring about the temperature in Flagstaff, Arizona, in the early morning of Wednesday, May 3—or in Fargo, North Dakota, in the late evening of Sunday, May 28? Are they looking for an answer in Fahrenheit or Celsius?

Most people would agree that the “temperature in America last month” question is absurd, but this is more or less what we get with regard to inflation. Once a month, the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) releases its headline consumer price index (CPI), which is supposed to give us some idea of how much or how little consumer prices changed compared to last month and last year.

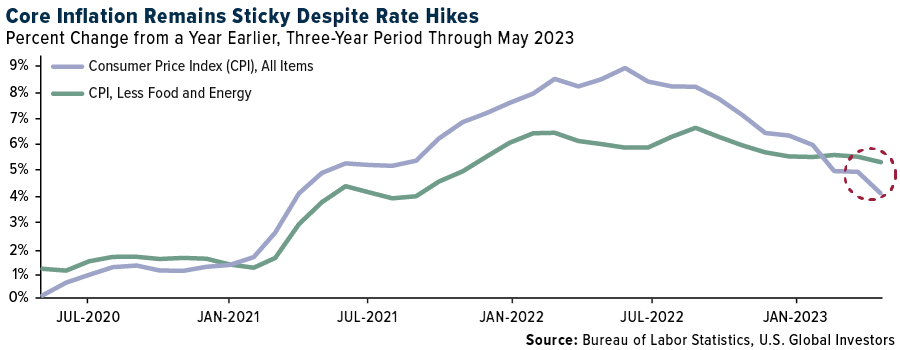

Last week’s CPI, for example, shows that prices in May continued to increase year-over-year, but at a much slower pace of 4%, down from nearly 9% in June of last year.

This makes it seem as if the Federal Reserve’s efforts to bring down inflation by hiking rates are working, but if we strip out volatile food and energy prices, the picture isn’t as rosy. The so-called core CPI—which measures everything except food and energy—shows that prices on average barely budged from May 2022 to May 2023.

I should add that the BLS has continued to revise its methodology over the years. If we still used the 1980s methodology, annual inflation would be closer to 12% than 4%.

Online Prices Saw Largest Monthly Decline Since Start Of Pandemic

Again, just like temperatures, prices can vary significantly state-to-state and even city-to-city. According to the American Automobile Association (AAA), the current average price for a gallon of gasoline is $3.00 in Mississippi, making it the cheapest in the country. In California, by contrast, a trip to the pump will cost you $4.87 per gallon on average, or nearly $2 more.

Similarly, prices can be higher or lower depending on whether you purchase something from a brick-and-mortar store or an online retailer. For years, the joke was that big-box retailers like Best Buy had become a showroom for Amazon. Have your eye on an expensive surround sound system? Best to experience it in person before buying it for cheaper online.

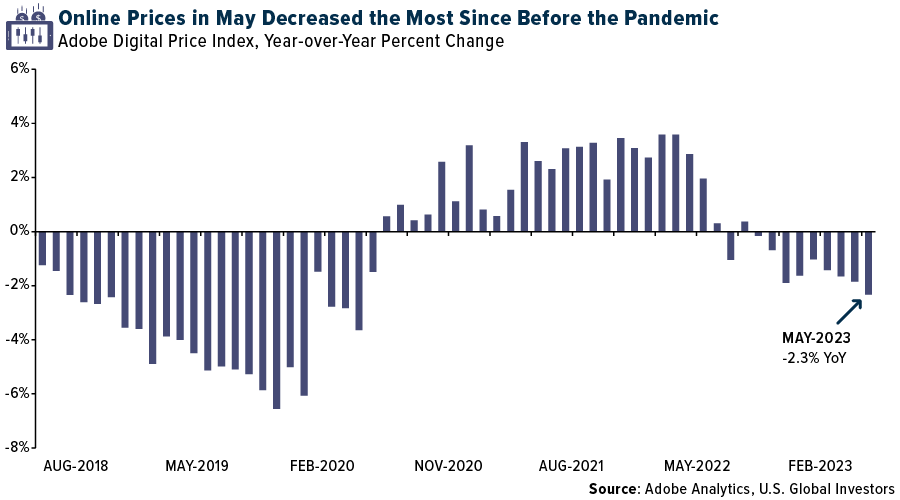

That said, the CPI only measures “offline” prices. BLS workers literally visit or call physical stores to get the price of select items.

For changes in online prices, we can turn to Adobe—the maker of the portable document format, or pdf, and Photoshop. Contrary to what you might think, Adobe is uniquely qualified to report on inflation trends, as its marketing and web analytics arm tracks an alleged 1 trillion visits to online retailers and over 100 million products across 18 different categories, from electronics to jewelry.

According to the company, online prices fell 2.3% in May compared to the same month last year. To clarify, prices didn’t just slow down, they got cheaper, and at the fastest pace since the start of the pandemic. Among the product categories that decreased the most were computers (-16.45%), electronics (-12.04%), appliances (-7.86%) and sporting goods (-7.39%). Categories that increased in price over the 12 months were personal care products, tools and home improvement, medical equipment, nonprescription drugs, clothes, groceries and pet products.

Will Fed Action Trigger Another Crisis?

My point in sharing this with you is to make it clear that measuring changes in consumer prices is a messy, imprecise undertaking, one that can result in conflicting data, as the difference between offline and online prices shows.

And yet these data are used by both the public and private sectors to guide important policy decisions, including cost-of-living adjustments, Social Security payments and more.

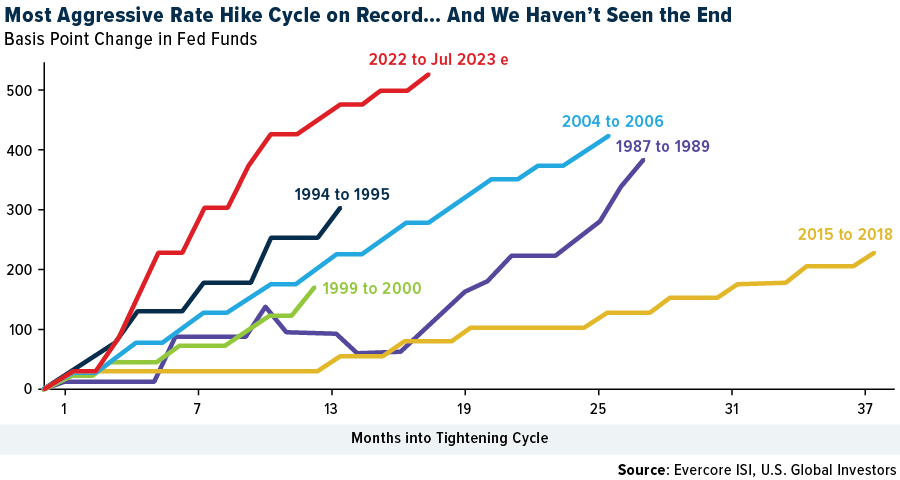

In perhaps the most well-known example, the Fed uses BLS data to inform monetary policy. Last week, the central bank elected to leave rates the same but indicated it may need to raise them at least two more times this year, despite the fact that this tightening cycle is already the most aggressive since at least the 1987-1989 cycle.

As Evercore ISI’s Ed Hyman put it last week, if we take the Fed’s balance sheet normalization into consideration, today’s effective rate is really around 6%. The regional banking crisis may be behind us, Hyman says, but the risk of “another financial shock/crisis in another area” rises as rates remain on an upward trajectory.

Preparing Your Portfolio For A High-Inflation, High-Interest Rate Environment

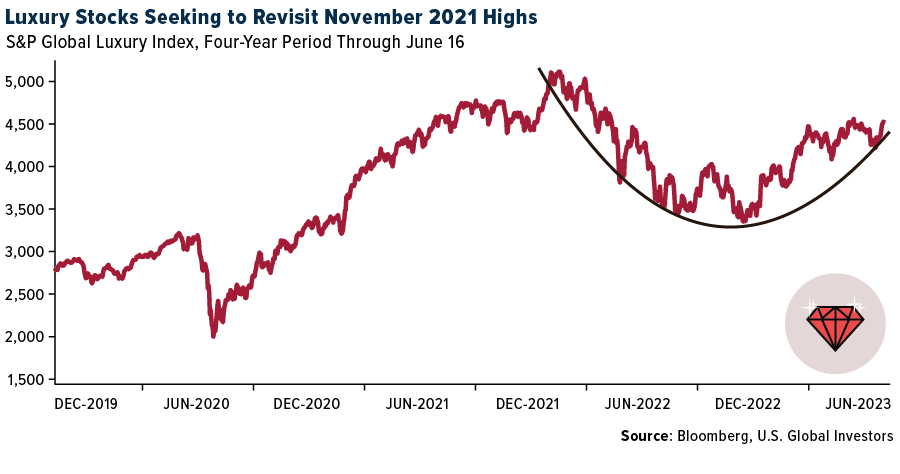

It may be impossible to say that any asset class or investment is immune to the kind of volatile swings in inflation and interest rates we’re seeing today, but luxury stocks are a strong contender, I believe. Because luxury brands tend to have decades of name recognition behind them, and because they limit supply, they’ve historically had incredible pricing power, able to raise prices without severely impacting demand from mostly affluent consumers.

Many luxury items have themselves been smart investments, with Hermès’ famous Birkin bag often outperforming the S&P 500 and gold. Between 2011 and 2021, the price of pre-owned Rolex watches beat advances in the stock market, gold and real estate.

The S&P Global Luxury Index, up a little over 20% year-to-date, is still below its all-time high set in November 2021, making now an attractive buying opportunity, according to Bank of America (BofA). Companies in the luxury industry are “likely” to continue beating earnings expectations as profits remain strong on buoyant sales, BofA analyst Ashley Wallace said in a note this week.

“Historically, pullbacks in the sector have been buying opportunities and this time will likely be no different,” Wallace wrote, adding that demand in China has continued to exceed expectations despite an underwhelming economic reopening.

Related: Cracking the Inflation Code