In 2019, I discussed the disconnect between the markets and the economy. After years of Central Bank interventions, stock markets have soared to record highs, while economic growth has remained weak. Mohamed El-Erian recently discussed the two primary risks heading into 2021.

El-Erian began his article by asking the most relevant question.

“What, if anything, will happen to the great disconnect between Wall Street and Main Street?”

The Great Disconnect

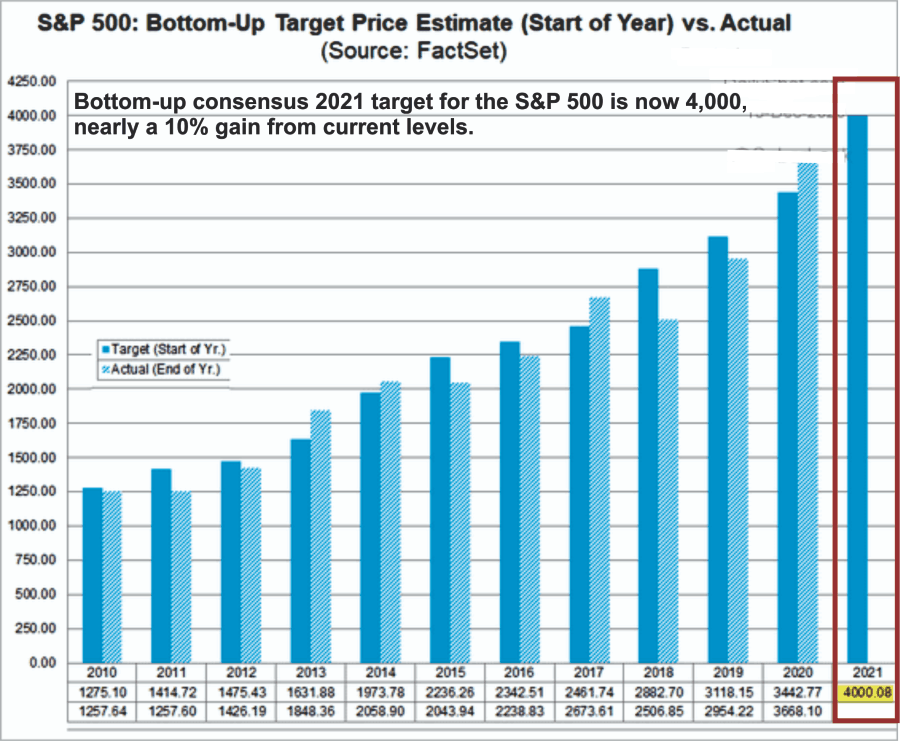

Currently, Wall Street analysts are projecting record stock markets in 2021, with stock prices rising another 10% and earnings surging toward record levels.

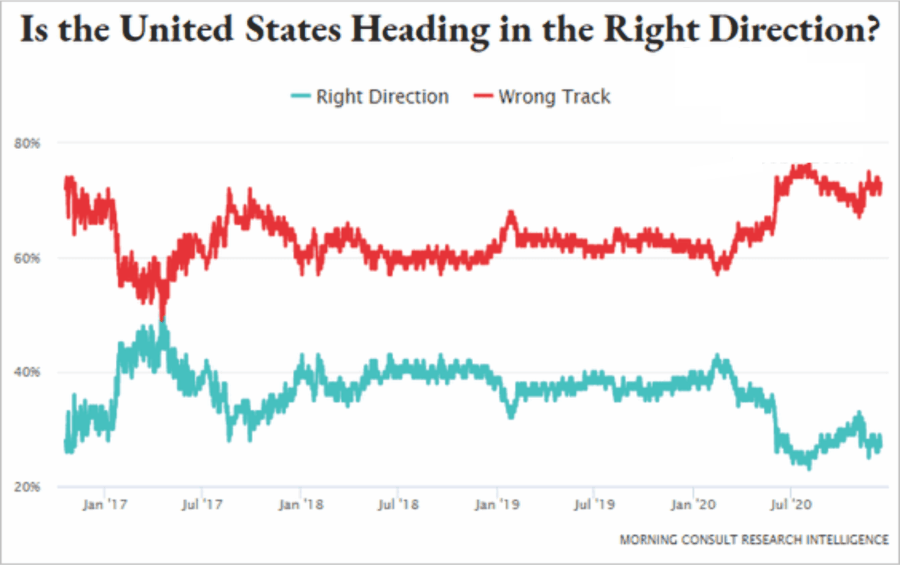

Main Street, however, believes the economy is heading in the wrong direction.

Such is the question we have discussed previously, given that the “stock market is ultimately a reflection of the economy.”

“The detachment of the stock market from underlying profitability guarantees poor future outcomes for investors. But, as has always been the case, the markets can certainly seem to ‘remain irrational longer than logic would predict.’

However, such detachments never last indefinitely.

The stock market is NOT the economy. But the economy is a reflection of the very thing that supports higher asset prices – corporate profits.”

Importantly, this detachment is now a key consideration for policy-makers and investors as we head into 2021.

A Remarkable Gap

“Throughout this pandemic year, we have experienced a further sharp widening of an already remarkable gap between financial markets and the economy. A rapid recovery in asset prices from the March 23 lows took major US indices to record levels, even before the recent good news on Covid-19 vaccines. Combined with even more accommodative central bank policies, this enabled record debt issuance at historically low levels of compensation for creditors.” – El-Erian

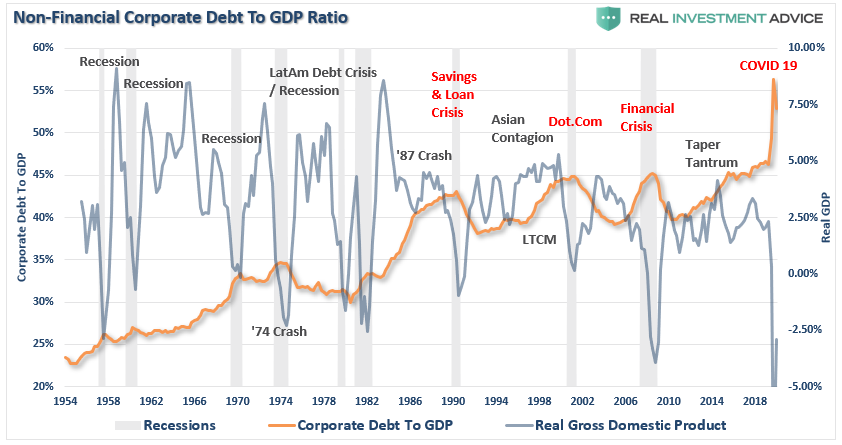

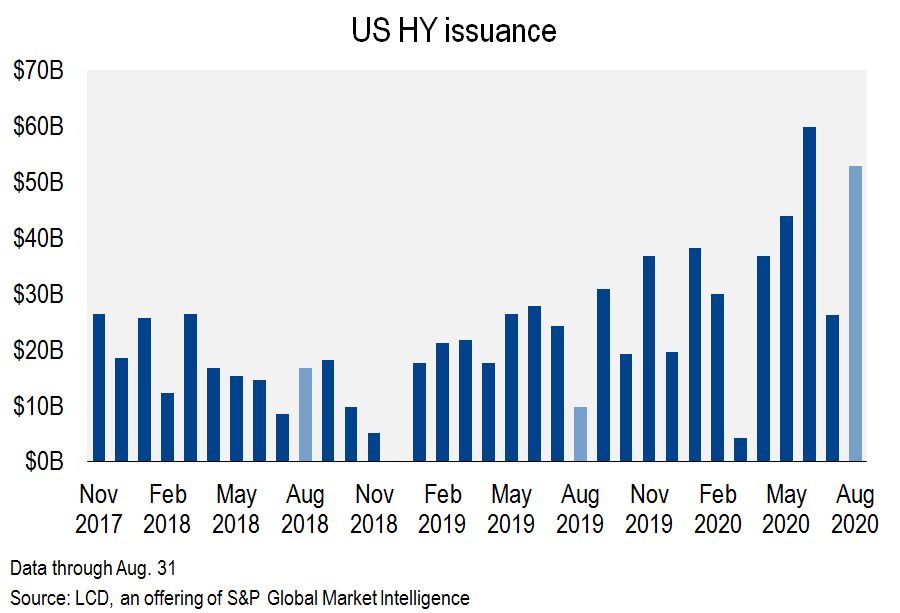

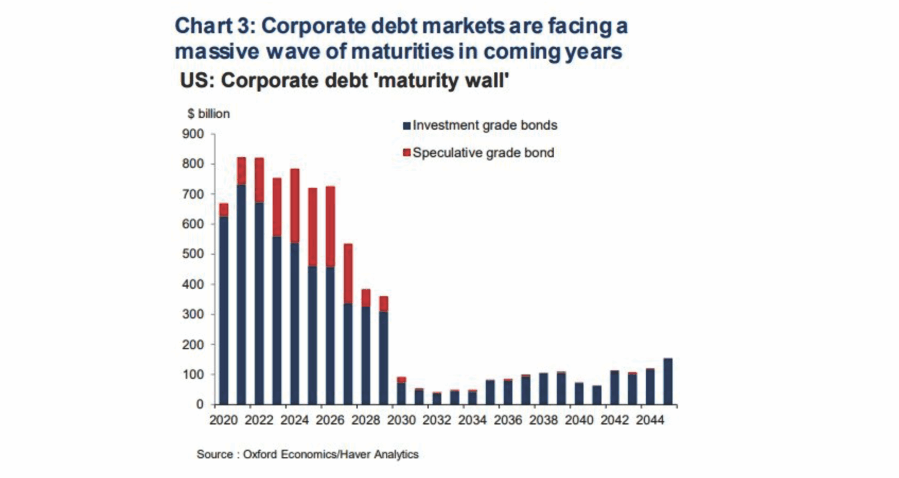

There is no doubt that corporations did indeed take the Federal Reserve up on both near-zero interest rates and a guaranteed buyer of bond issuance. In 2020, investment-grade bond issuance hit a record with total non-financial debt soaring to all-time highs. Such was occurring at a time when revenues and profits were plunging.

That data includes the record levels of “junk bond” issuance in the market.

“Issuance in 2020 through August was $291.9 billion, up 71% year over year. Credit strategists at BofA Global Research now project a full-year primary volume of $375 billion. Such would shatter the current record total of $344.8 billion in 2012, according to LCD.”

Of course, the issue is that over the next few years, there is a tremendous amount of debt coming due. If rates risk markedly, or if the market demands payment for the relative risk, refinancing could become problematic.

The other problem is if the economy fails to have a robust economic recovery as Wall Street currently expects.

Expectations For Recovery May Fall Short

There is a significant problem currently which we discussed in “Recessions Are A Good Thing:”

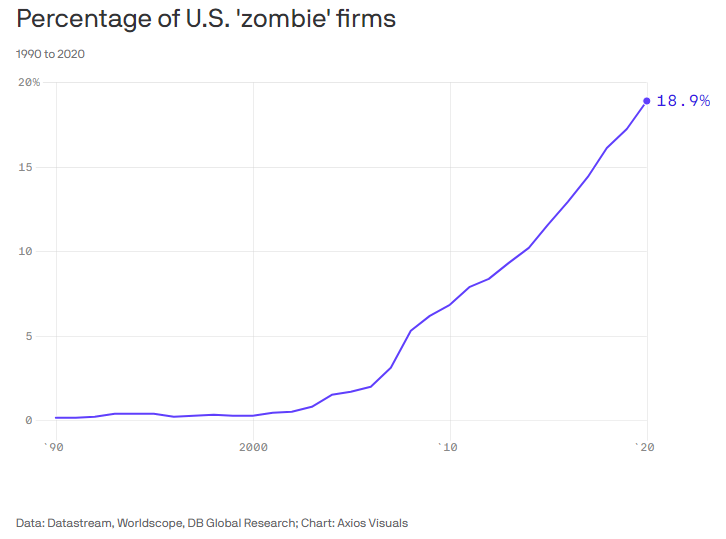

“‘Zombies’ are firms whose debt servicing costs are higher than their profits but are kept alive by relentless borrowing.

Such is a macroeconomic problem. Zombie firms are less productive, and their existence lowers investment in, and employment at, more productive firms. In short, a side effect of central banks keeping rates low for a long time is it keeps unproductive firms alive. Ultimately, that lowers the long-run growth rate of the economy.” – Axios

The number of “Zombie” companies in the market has hit decade highs in 2020. The massive Federal Reserve interventions, bailouts, and zero rates provided the life support failing companies needed. From a market perspective, the Federal Reserve’s liquidity flows increased speculative appetites, and investors piled into “zombies” with reckless abandon.

These companies’ survivability is based upon a continued low rate environment, a robust debt market, and economic recovery to ensure the ability to repay debt holders.

However, the “recovery” may not be nearly as strong as Wall Street currently expects.

An uncertain economic outlook with notable dispersion among systemically important countries is but one of the Covid-19 legacies that markets have set aside due to sky-high faith in central banks’ ability to shield asset prices from unfavorable influences.” – Mohamed El-Erian

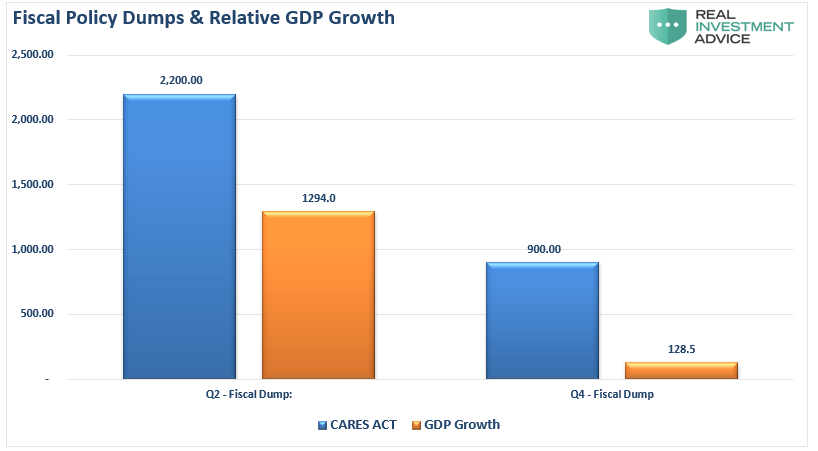

Even with a “Second Stimulus,” the underlying erosion of economic growth from rapidly rising debts and deficits leaves little margin for error.

“[The economy] requires increasing levels of debt to generate lower rates of economic growth. The chart shows both CARES Acts and the impact on GDP growth.”

Such is why the Federal Reserve has found itself in a “liquidity trap.”

Rates MUST remain low, and debt MUST grow faster than GDP, to keep the economy from stalling out.

Moral Hazard

In the short-term, however, market participants have been lulled into a false sense of security. Currently, investors are paying astronomical prices for “risk” assets. At the same time, they accept low rates on “high yield” debt (aka junk bonds) relative to the risk of default.

The detachment of investor attitudes from the underlying risk is precisely the definition of “Moral Hazard:”

“Noun – ECONOMICS

The lack of incentive to guard against risk where one is protected from its consequences, e.g., by insurance.”

As Mohammed El-Erian specifically noted:

Markets being markets, investors have readily extended the protective nature of the umbrella to asset classes that, at best, are only indirectly supported by central bank funding (such as emerging markets).

It is an extremely powerful dynamic, and one that inevitably overshoots.

In other words, investors “believe” they have an insurance policy against “risk.”

Nothing is more reassuring to an investor than the knowledge that central banks, with much deeper pockets, will buy the securities they own — particularly when these buyers are willing to do so at any price and have unlimited patient capital.

The rational investor response is not just to front-load their buying but also to look for related opportunities where return-seeking funds will be pushed to. The result is not just seemingly endless liquidity-driven rallies regardless of fundamentals.

Such does seem to be the case until an unexpected exogenous event occurs, or if the Fed tries to normalize monetary policy. In either event, the underlying “risk” becomes quickly realized as a “financial crisis.”

The resulting destruction of household net worth requires an immediate response by the Fed of zero interest rates and liquidity. Subsequently, they are forced to create the next “bubble” to offset the deflation of the last.

Irrational Exuberance

Importantly, what the Federal Reserve did accomplish was creating a demand for “risk” assets by distorting market functions and price discovery. As El-Erian noted:

“While investors will continue to surf a highly profitable liquidity wave for now, things are likely to get trickier as we get further into 2021. Central banks’ deepening distortion of markets will be harder to defend in a recovering economy amid rising inflationary expectations.

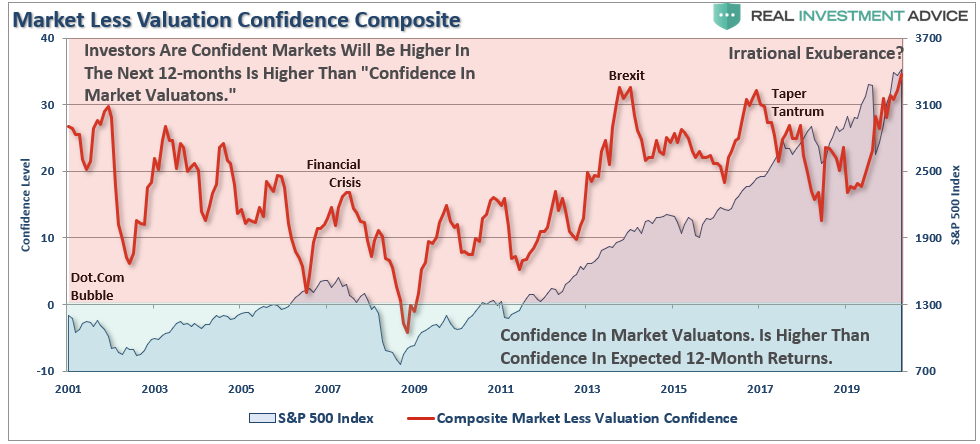

Nowhere is this more evident than in recent surveys that show an extremely high level of investor exuberance despite the underlying detachment from fundamentals.

“The chart below shows the combined average of institutional and individual investor valuation confidence subtracted from future returns confidence. When the reading is positive, the confidence the market will be higher one year from now is more elevated than the confidence in the market’s valuation. The opposite is the case when the reading is in negative territory.

The key takeaway is that investors think simultaneously, the market is over-valued but likely to keep climbing.” – Charting 2020’s Speculative Mania

Such is the same phenomenon famously described by former Fed Chair Alan Greenspan in a December 1996 speech on “Irrational Exuberance.”

Whenever such detachments between the real economy and markets have previously occurred, investor outcomes have not been kind. It is unlikely this time will be different.

Investors might rue the day they ventured into asset classes far from their natural habitat that lack sufficient liquidity in a correction. Navigating such a landscape will require analytical tools that would, ironically, have detracted from returns during the bulk of the liquidity-driven rally.” – El-Erian

The Wealth Gap Explodes

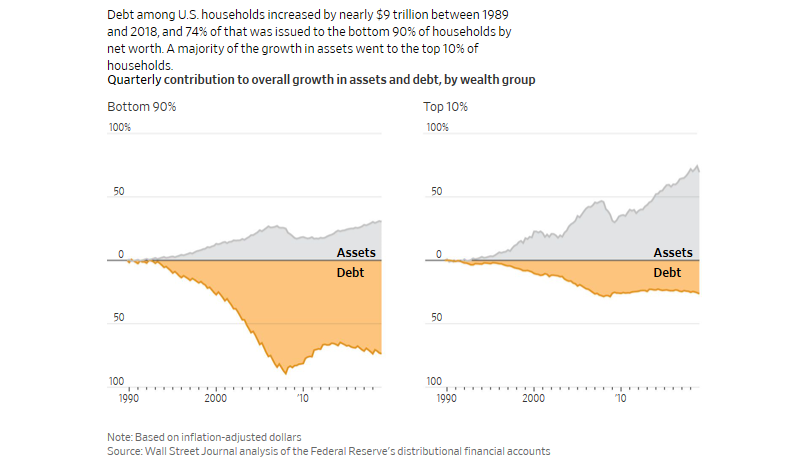

The problem of the disconnect between the economy and the markets is that it is unsustainable long-term. According to the Economic Policy Institute, the top 1% take home 21% of all income in the United States, the largest share since 1928.

There are various social, political, and economic factors driving this growing discrepancy, but one critical factor is ignored – The Federal Reserve. When the Fed inserted itself into the economic equation, their contribution led to rising imbalances between economic classes.

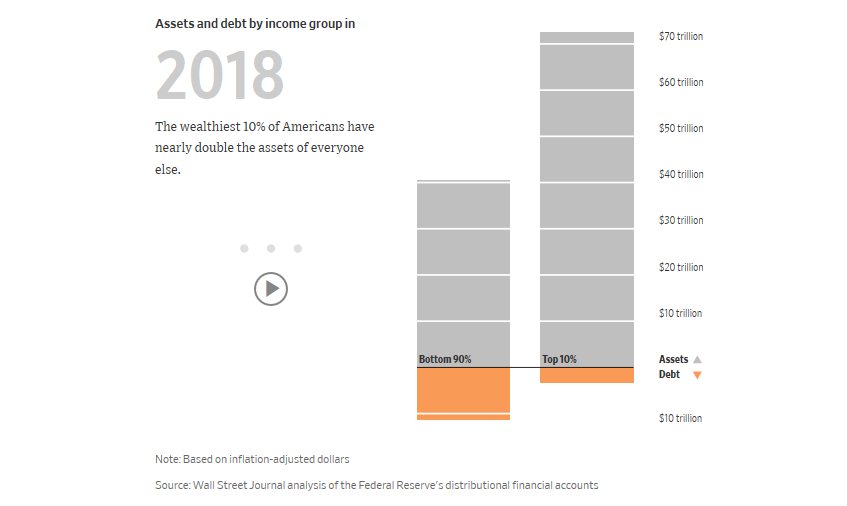

Over the last decade, as stock markets surged, household net worth reached historic levels. If one just looked at the data, it was clear the economy was booming. However, for the vast majority of Americans, it wasn’t. The WSJ showed this previously:

“The median net worth of households in the middle 20% of income rose 4% in inflation-adjusted terms to $81,900 between 1989 and 2016, the latest available data. For households in the top 20%, median net worth more than doubled to $811,860. And for the top 1%, the increase was 178% to $11,206,000.”

Put differently, the value of assets for all U.S. households increased from 1989 through 2016 by an inflation-adjusted $58 trillion. A full 33% of that gain—$19 trillion—went to the wealthiest 1%, according to a Journal analysis of Fed data.

No Longer Sustainable

What policy-makers, and the Federal Reserve missed, is the “stock market” is NOT the “economy.”

This “wealth gap” can be directly traced back to a decade of monetary policy that almost solely benefited those who either had money to invest in the financial markets or were compensated through increases in corporate asset prices. However, those policies failed to produce substantial rates of either wage growth or full-time employment.

The reality is that we have likely reached the efficacy of monetary interventions. As such, El-Erian’s concluding comment is most important.

“Already, the great disconnect has continued much longer than most expected. This illustrates, yet again, the unintended consequences of a policy approach that places an excessive burden on central banks.

There are two risks, and not just for markets.

First, what is desirable may not be politically feasible, and second, what has proven feasible is no longer sustainable.”