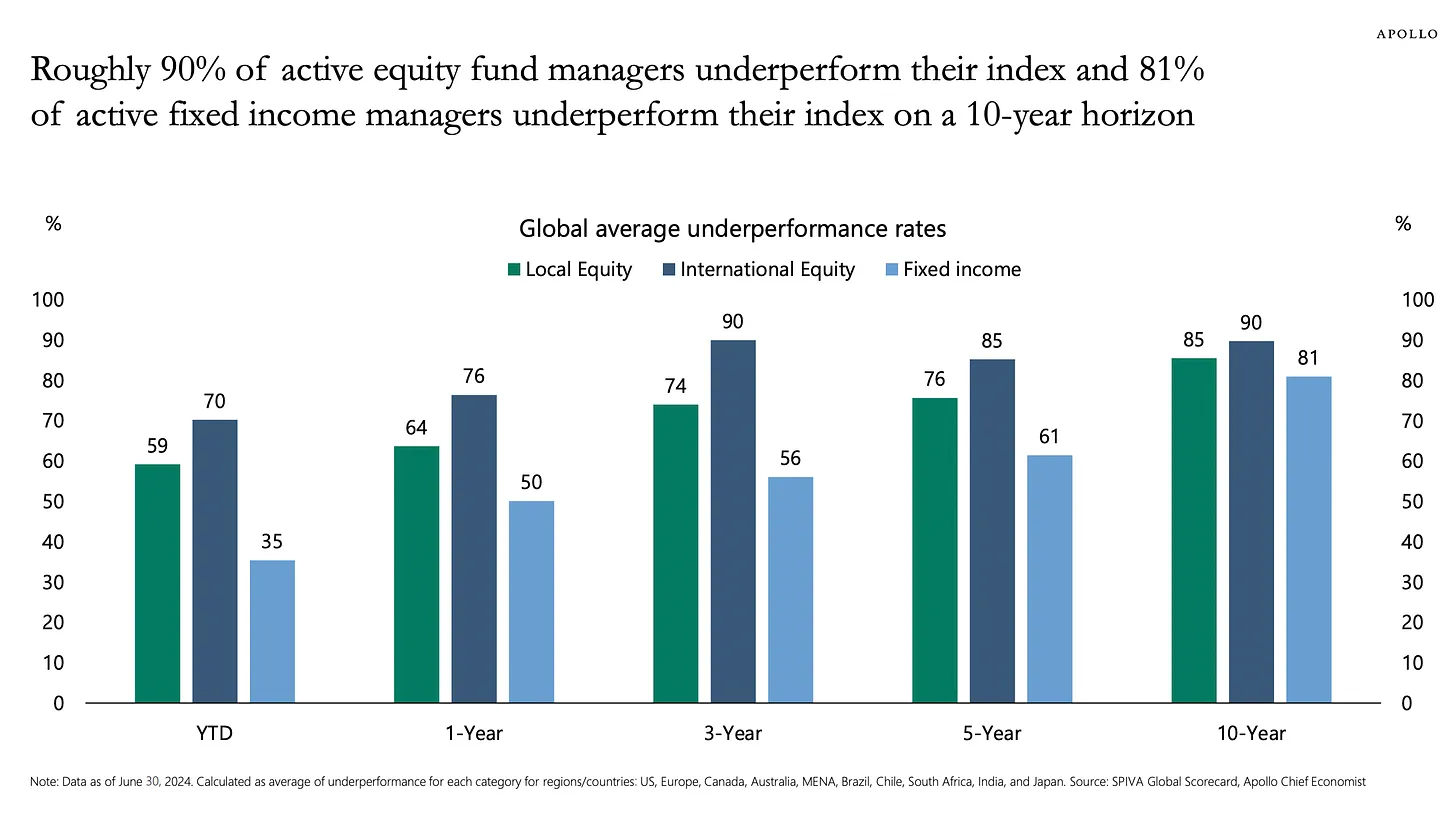

The above chart, based on an S&P study, reached my inbox by way of Torsten Slok, Apollo’s Chief Economist. Torsten produces The Daily Spark — a terrific financial blog providing important insights into our financial world, all in bite-sized chunks.

The chart considers the performance of domestic equity, foreign equity, and fixed income active-fund managers throughout the financial world. The findings for U.S. managers are little different. Take U.S. active equity fund managers. Year to date, over half — 57 percent — underperformed the S&P 500. Over the past five years, 77 percent underperformed the market. And over the past decade, 85 percent missed the mark.

If the misses were small, no big deal. But they can be major. Since January, the S&P has yielded 15 percent. But one in four large-cap, actively-managed equity funds recorded returns of 8 percent or less. And this doesn’t include the loads the funds charge — loads often above 1 percent.

The Case for Active Management

Blackrock’s Tony DeSpirito argues that active investment even in large-cap stock funds makes sense since the best of these funds outperform the rest by a significant margin. Here’s a quote:

Skill does matter. The alpha (excess return over the S&P) generated by median managers has been negative in 67% of rolling one-year periods over the past 10 years. Yet the top quartile of alpha generators remained positive and posted returns as much as 16% higher than bottom-quartile managers since 1995.

The typical difference between superior and inferior managers averages 6 percentage points. More important, fund managers that outperform their competitors in one year are highly likely to underperform them the next. DeSpirito seems to be implicitly assuming that we can all be lucky enough to find an active stock manager who both consistently beats the market and doesn’t charge a commensurate higher load for doing so.

DeSpirito also argues that market-weighted index funds effectively put most of our eggs in one basket. The “Magnificent Seven” — Apple, Microsoft, Alphabet, Amazon, Nvidia, Tesla, and Meta — the largest seven firms in the S&P 500, now comprise about 30 percent of the index. That’s substantial concentration, but certainly not unprecedented in the history of the stock market.

Does such concentration really represent a reason not to invest in the entire stock market via a low cost index fund? Some of these funds have loads as low as 0.3 percent, which is essentially zero.

Obviously, one could invest an equal amount of one’s stock holdings in each of the more than 5,500 stocks listed in the U.S. market. But that would put almost all of one’s money in a very small share of the economy since most of the listed companies are puny compared to the Fortune 500 let alone the Mag 7.

Still, I get DeSpirito’s concern. The S&P is top heavy in a small number of high-tech firms whose stocks have been moving in parallel of late. This makes Mag 7 firms riskier than would otherwise be the case.

But assets that are riskier sell for less in the market due to that extra risk. Stated differently, the pricing of financial assets, including Mag 7 stocks, makes it worth our while to hold them, even with their extra risk, as long as they aren’t dominated by other assets — assets that offer the same state-specific returns at lower risk. Crypto currencies, by the way, appear to be dominated assets. (See this column: Does Casino Gambling Beat Cypto Investing? )

In short, the correlation of the returns of our nation’s seven largest firms with one another doesn’t alter economics’ standard portfolio separation theorem supporting holding all non-dominated assets in proportion to their share of the entire financial market’s valuation. The theorem rests on some generally applicable assumptions including the assumption that the returns on any non-marketed assets you hold aren’t correlated with specific securities in the market-weighted index.

What’s an example of an asset that could be so correlated? Well, suppose you worked for Microsoft. Now the return on your primary financial asset — your human capital — would be correlated with Microsoft’s stock market performance as well as that of the other Mag 7 firms. In this case, you’d want to short Microsoft to, in effect, buy labor-income insurance. If Microsoft tanks and you lose your job, your short position will appreciate and offset the cost of your job loss. As for holding the other Mag 7 stocks, you’d want to build your own portfolio (or have your advisor do so) that held little or none of those securities whose return was highly correlated with that of Microsoft.

Which Active Mutual Fund and Investment Advisor Should I Pick?

There are over 7,000 mutual funds investing in domestic equities, foreign equities, dividend-paying equities, small cap equities, fixed income, commodities, real estate investment trusts, and other assets or combinations of these assets. Moreover, if you’re investing in specific mutual funds or, indeed, in individual securities, you’re likely doing so on the advice of a trusted financial advisor. There are some 300,000 of such professionals on the market.

Those working for mutual fund companies will surely suggest you purchase their company’s funds. But not every advisor, let alone mutual fund, can perform above average. And, as the S&P chart shows, the distribution of good and bad performers is not symmetric. There are more underperforming funds and advisors than there are overperforming ones.

I’m not suggesting rushing to sell off your portfolio and investing just in low-cost, index funds (i.e., holding the market rather than trying to beat the market). Doing so might force you to pay capital gains taxes, which may be best to defer. Nor am I suggesting you fire your advisor. They may be providing solid financial advice that goes far beyond how to invest your savings. They may, for example, be helping you sort our your impending divorce. I am suggesting you pay attention to the chart and decide whether your portfolio is riskier or more expensive than necessary and whether your advisor is worth their annual cost.

Financial Psychosis

I help lots of people directly or indirectly via MaxiFi Planner with their financial plans, although neither I nor my company’s software provide specific investment advice. What I’ve come to appreciate is the degree to which fear, emotion, and inertia influence the financial moves so many of us make and, more important, don’t make.

Most people who learn I’m an economist and have developed financial planning software quickly start asking me financial questions, which leads me to start asking them financial questions. The majority tell me they don’t do financial planning. When I ask why not, they either say they are too scared or that they don’t need to plan.

For those saying they are too scared, I explain that they may be worried about something that isn’t real or, if it is, will likely get worse if left unaddressed. Those who are sure they don’t need to plan, including, btw, most economists, claim they are sure they are financially fine; their 401(k) and Social Security are enough. Alternatively, they say they can can’t find the time to plan. I respond that relying just on our employers and Uncle Sam generally leave us miles short in terms of retirement resources, that financial planning is immensely complex, that one needs super sophisticated software to get it right, and that in not properly planning, they are likely leaving large mounds if not mountains of money on the table.

As for those with advisors, it’s “My advisor is taking care of me. She’s really smart. I’ve worked with her for years. She tells me I’m fine. I trust her. She’s trained. She has some kind of training. She’s a certified something. I leave everything to her. She lists all my assets on one page. She’s also my cousin. And, no, I don’t really know where I stand. She says I’m fine. I’m fine.”

My Friend Jane

Let me relate one actual example of financial psychosis involving my friend, Jane. Jane’s a marketing manager. Jane’s been worried for years about her finances. But she’s literally been too scared, terrified actually, to run MaxiFi Planner. I told Jane to send me her data. I’d run the program for her — for free, of course — and that it would take me all of ten minutes to understand her situation. I also explained about MaxiFi’s ability to find extra money for her in them their hills in the form of higher lifetime Social Security benefits, lower lifetime taxes, and making other safe financial moves.

It took three years, but Jane finally relented. MaxiFi showed, in the predicted ten minutes, that Jane was actually in solid financial shape and could safely sustain a high sustainable living standard were she to invest primarily in a ladder of Treasury inflation-protected bonds, leaving a share of assets in the market to provide upside potential to her living standard. (This podcast shows that building a TIPS ladder is super easy. And this one shows how to use MaxiFi to do Upside Investing.)

Then I asked Jane about her investments. Jane said she was invested with an advisor named Kathy. Kathy, Jane said, had been managing her money for years. Kathy was great and fun. She had met Kathy socially. Kathy had gotten her to move her money from Ralph who had put her in annuities that Kathy hated and had sold. She was glad to move. She had never liked Ralph. Kathy has had training. What kind of training? Not sure. Did she have a degree in finance? No.

I asked Jane to send me the list of her investments. She said she would. Four months of bugging later, the report arrived. Kathy had invested Jane in 37 different mutual fund — all with loads ranging from .5 percent to 1.5 percent. The loads were costing Jane close to $20K per year — about 15 percent of Jane’s take home pay.

Each of the mutual funds had a different name suggesting they were doing something different. They each held lots of different securities, mostly stocks and nominal bonds, i.e., bonds whose real returns, unlike TIPS held to maturity, are risky to inflation.

Investing’s Dirty Little Secret

Economists have known for years that you can get essentially all the risk-mitigation value from diversifying your portfolio by holding a small number of financial assets chosen at random. This is no different from saying that buying 16 different one-once cuts of beef will give you essentially the same pleasure as buying a single, one pound steak.

Hence, when I saw Jane’s holdings my instant reaction is “She’s purchased 37 one-once pieces of beef.” Yes, the once of ribeye was somewhat different from the once of sirloin, which was somewhat different from the once of porterhouse, which was … . But the epicurean pleasure as well as total cholesterol was essentially identical to buying a single 37-once Tomahawk steak. The only real difference was the cost. In combination, Jane’s 37 mutual funds, each with their 30 to 80 different securities, was no different from buying a combination of a total stock market index plus a total bond market index. Both indicies can, I explained, by held essentially for free.

The Rest of the Story

Jane now holds a ladder of TIPS and a very low-cost total stock market index as well as a low-cost international stock market index. The $20K she was spending on Karen is now being used to help her daughter pay off her student loans. She’s still working with Karen. But she’s having Karen invest her in Karen’s company’s market index U.S. and international stock funds. She also had Karen purchase her TIPS ladder and will have Karen handle the reinvestment in TIPS of her every-six-month TIPS coupons.

A PS Message for Financial Advisors

Beating the market is beating your head against the wall. Better to use your expertise to do deterministic planning for households, i.e., helping them decide where their kids should attend college, how their kids should handle their students loans, whether to switch jobs, when to retire, how much to save, whether and when to do Roth conversions, when to downsize, how much life insurance they need, whether to move to a no-tax state, how much they can afford to leave their kids, when to take their pensions, how to maximize their Social Security, and the list goes on.

As for investments, most clients want to preserve their living standards but still play the best casino going — the stock market, which offers, on average, a super high real return albeit with considerable risk. The simple means of satisfying both client interests is running them through MaxiFi’s Upside Investing routine.

Upside Investing has your client spend only out of safe assets (e.g., TIPS) while investing, in part, in stock. When, down the road, the stocks are sold, they are converted to TIPS and used to raise your client’s living standard. By spending only out of TIPS, i.e., treating money in stocks and other risky assets as lost until it is found, the client only experiences upside living standard risk. In short, downside living standard risk depends not just on risky investing, but also on risky spending. Spending out of assets that you expect to perform, but can’t count on for sure, is risky spending (entailing sequence of return risk) that sets you up for a drop, if not a plunge, in your living standard.

Related: Why Factories Aren't the Future: Martin Eichenbaum on U.S. Tariff Risks