For decades, the process that companies in the United States have used to go public has followed a familiar script. The company files a prospectus, providing prospective investors with information about its business model and financials, and hires an investment banker or bankers to manage the issuance process. The bankers, in addition to doing a roadshow where they market the company to investors, also price” the company for the offering, having tested out what investors are willing to pay, and guarantee that they will deliver that price, all in return for underwriting commissions. During the last decade, as that process revealed its weaknesses, many have questioned whether the services provided by banks merited the fees that they earned. Some have argued that direct listings, where companies dispense with bankers, and go directly to the market, serve the needs of investors and issuing companies much better, but the constraints on direct listings have made them unsuitable or unacceptable alternatives for many private companies. In the last three years, SPACs (special purpose acquisition companies) have given traditional IPOs a run for their money, and in this post, I look at whether they offer a better way to go public or are more of a stop on the road to a better way to go public.

What is a SPAC?

The attention that SPACs have drawn over the last few months may make it seem like they are a new phenomenon, but they have been around for a long time, though not in the numbers or the scale that we have seen in this iteration. In fact, “blank check” companies had a brief boom in the late 1980s, before regulation restricted their use, largely in response to their abuse, especially in the context of "pump and dump" schemes related to penny stocks.

SPAC structure

To understand how the modern SPAC is different from the blank check companies of the 1980s, let’s revisit the regulations written in 1990 to restrict their usage. To protect investors in these companies, the SEC devised a series of tests that need to be met related to the creation and management of blank check companies:

- Restricted purpose: The company has to have the singular purpose of acquiring a business or entity. Thus, it cannot be used as a shell company that chooses to alter its business purpose after the acquisition.

- Time constraints: The acquisition has to be completed within 18 months of the company being formed or return the cash to the its investors.

- Use of proceeds: The IPO proceeds, net of issuance costs, from the company going public have to be kept in an escrow account, invested in close to riskless investments, and returned if a deal is not consummated.

- Shareholder approval: During the process of finding an acquisition target and accomplishing the acquisition, shareholder approval is required, first when the target company is identified, and later when the acquisition price and terms are agreed to. As a prelude to shareholder approval, they have to be provided with the financial information on the proposed target and the necessary information to make an informed judgment.

- Opt out provisions: If shareholders in the company choose to redeem their shares, they are entitled to get their initial investment back, net of specified costs, but with interest earned.

While these restrictions were onerous enough to stop the blank check company movement in its tracks, special purpose acquisition companies (SPACs) eventually were created around these restrictions. A SPAC is initiated by a sponsor, a lead investor who brings or claims to bring special skills to the acquisition process, either because of an understanding of an industry in which they plan to find a target or because of deal making skills. As sponsors, they receive a significant stake (~20%) in the SPAC (called a promote), contributing little or nothing to capital, and in addition to finding and negotiating the price for a target company, they sometimes provide more capital to the target company through PIPEs (private investment in public equity). The picture below summarizes the time line for a SPAC, and the role of the sponsor along the way:

Unlike the blank check companies of the 1980s, investors in SPACs get multiple layers of protection, both in terms of being able to approve or reject the choice of target companies and the terms of the deal, as well as being able to redeem their shares and receive their money back, with interest, if a deal is not done, or if they are dissatisfied with a proposed target/deal. That said, the SPAC sponsors are clearly in the driver's seat, not only because they are the deal makers, but also because they control a significant portion of the shares in the deal, much of it subsidized by other SPAC investors. At the end of the time window (usually, eighteen months to two years), the SPAC is wound up, with success (an approved merger) resulting in the target company becoming a publicly traded company, and failure (no target found or target deal rejected) translating into a return of cash to the SPAC investors. In a significant proportion of SPACs, the sponsors create an entity (a private or PIPE) to supply additional capital, with two reasons for the add on. The first is to provide additional capital, if needed, for the target company in the deal for its business needs. The second is to cover capital withdrawals from SPAC shareholders who choose to opt out and get their money back.

Going Public? The Choices

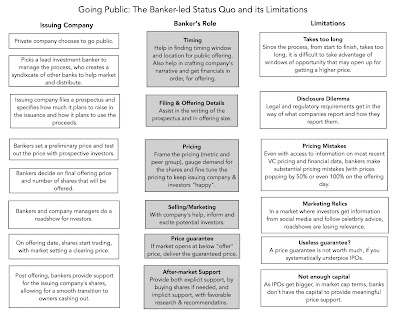

The process that a private company follows to go public, for the last few decades, has been built around bankers as intermediaries. Borrowing from an earlier post on the topic, I have summarized the traditional IPO process, with a list of reasons of why many venture capitalists and issuing companies have soured on the process:

Put simply, the traditional IPO process takes too long, costs too much and leaves both issuing companies and investors dissatisfied, the former because the the process takes too long and is too inefficient, and the latter because they feel that only a select few can partake at the offer price.

While banker-led IPOs will not disappear, you can see why the search is on for alternatives. In my earlier post, I looked at direct listings, where the company dispenses with the banking services (setting an offering price and roadshows) and lets the market set the price on the offering date.

This process, by doing away with the banking intermediaries, is less costly but it still takes time and comes with constraints, especially in the context of raising capital from the offering to cover future business needs. It may also be difficult for low-profile private companies to list directly, when investors are reluctant to invest based upon a prospectus, without someone else doing the due diligence (asking questions of management, checking the financials).

Looking at SPACs in the context of banker-run IPOs and direct listings, you can see some of the reasons for their surge in popularity. First, since SPACs go public and raise capital first, and then go on a search for targets, they may be more time efficient, where they can do deals to take advantage of short windows of market opportunity. Second, on the disclosure front, while the information disclosure requirements for SPACs largely resemble those for conventional IPOs, SPACs have more freedom to make projections and spin stories, albeit with basis and within reason. Finally, the SPAC sponsors take on the search and deal-making roles, using their industry knowledge to do due diligence and negotiate the best prices, in effect replacing investor due diligence with their own.

The benefits of the SPAC route to going public have to be weighed against its many costs. The first is that the SPAC sponsor's subsidized share of the SPAC (which can amount to more than 15-20% of the capital raised) and the deal-making costs (underwriting fees are 5% or more of the merger value) may be large enough to wipe out any potential timing and pricing benefits in the deal. The former effectively dilutes a SPAC investor's holding, right at the start, and the latter drains value from the deal. The second is that the SPAC sponsors, notwithstanding the protections built in for investors, are in control not only when it comes to the deal making, but also of the side aspects on the deal that can benefit them disproportionately. For instance, the capital provided by a PIPE in a SPAC can be at a discounted price, relative to the deal price. Finally, to the extent that SPACs are being marketed as being good for private companies planning to go public, because they allow these companies to time their offerings better and receive higher market prices, it is worth noting that these benefits come at the expense of investors in these SPACS. In other words, SPACs claiming that they deliver value to both issuing companies and to their own investors are trying to eat their cake and have it too.

The Rise of SPACs

As noted at the start of this post, the SEC regulations put into place in 1990 to restrict the use of blank check companies removed them from the market landscape for about a decade. It was not until 2003 that the modern SPAC was born, but its usage stayed limited until 2016. In fact, the real boom in SPACs has been in the last three years, with the pace picking up in the second half of 2020 and in 2021:

In 2020, SPACs accounted for more than half of all deals made, in terms of dollar value, and SPACs are running well ahead of that pace in 2021. Since there were no regulatory changes in 2020 that could explain the dramatic rise, the explanations for the surge have to lie in developments in the market and I would list four contributing factors:

- Low interest rates: Investors in SPACs effectively give up use of their proceeds, while the sponsors look for a deal. In a world, where interest rates were higher, the opportunity cost of idle cash may have repelled some investors, but in a world where interest rates, even on long term investments, is close to zero, that is not the case.

- High stock prices: It is no coincidence that the explosion in SPACs has come about while markets have been booming, and especially so for high-growth companies. There are two benefits that SPACs derive, as a consequence. The first is that the opt out clauses that SPAC investors possess to return their shares and ask for their money back are less likely to be triggered in up than down markets. The second is that investors tend to be sloppier and more willing to outsource their analysis and decision making, when markets are rising than when they are falling.

- Where pricing rules: Not only have markets been rising steeply for most of the last three years, but they have also been centered on the pricing game, where mood and momentum rule the roost, rather the value game, where fundamentals are key drivers. Since getting the timing right is key in the pricing game, it is not surprising that investors are attracted to SPACs, which at least in theory, are better positioned to take advantage of shifts in mood and momentum.

- And celebrities move markets: Markets have always had their sages and gurus, who move markets with their views and perspectives, but until recently these market movers were either investors with long track records of success (Warren Buffett is the iconic example) or perceived rule-changing powers (Fed chairmen, Presidents). The last decade, though, has seen the rise of celebrity market movers, including not just Mark Cuban, Elon Musk and Mark Cuban, who have some basis for their investor following, but also social media influencers, whose primary claim to fame is the number of people that track and follow their ideas. It cannot be a coincidence that many SPACs have signed up athletes and actors, hoping perhaps to use their followers to advance their investing aims, and that some of the highest profile SPAC sponsors are masters of social media.

In sum, SPACs are as much a reflection of the times that we live in, as they are a potential solution to the going-public problem. As market fervor fades, and fundamentals reassert their importance, it is inevitable that there will be a pull back from the highs, but I think that SPACs are here to stay.

Disentangling the SPAC effect: Cui Bono?

I am neither a lawyer, nor do I know Latin, but I love the expression, Cui Bono (Who benefits). When faced with a shift in market practices, it is worth asking the question of who benefits and at whose cost, and with SPACs, and to answer this question, it makes sense to start by looking at who invests in SPACs, how SPACs are structured, and how investors use (or do not use) their powers to cash out, before or after a deal. In perhaps the most comprehensive look at the phenomenon, researchers at Stanford and NYU law schools took a look at SPACs last year, and in addition to finding that 85-90% of investors in SPACs are large institutions, they record a troubling fact. While SPAC shares raise $10 per share at the time of their offering, the median SPAC holds only $6.67 per share, at the time it seeks out a target, with the loss due to the dilution caused by subsidizing sponsor ownership and other deal-seeking costs.

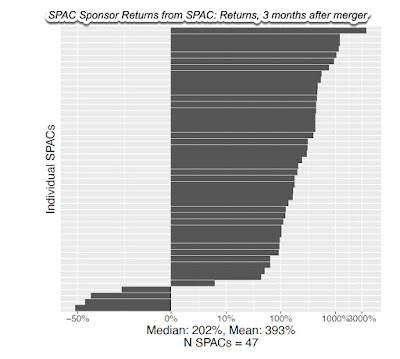

- SPAC Sponsors: The sponsors of SPACs, at least given their current structure, are the clear winners from this trend. When you receive shares of ownership that are three, four or even five times your invested capital stake, you have effectively tilted the game in your favor. At worst, if the deal does not go through, you return the cash to your investors, and walk away almost unscathed (at least, as an investor). If a deal does get done, you get a multiple of your original investment, presumably as compensation for finding a target, and negotiating the price. In the research study quoted above, the returns to SPAC sponsors reflect these advantages they bring to the game:

Source: Klaussner, Ohlrogge and Ruan (2021) - Investors in SPACs: There are clearly some deals, where SPAC investors emerge as winners, as the merged company's stock price soars in the aftermath. An investor in the SPAC that took Draftkings public in 2019, for instance, would be showing returns of more than 500% in the period since, and an investor in the Virgin Galactic IPO would have more than quadrupled their money. That anecdotal evidence, though, obscures a more mixed story, and to understand it better, you have to examine SPAC investor returns in two periods, one from the time a SPAC is taken public to when it announces a merger deal, and one from the weeks and months after the merger deal. In one study, researchers looked at 110 SPACs from 2010 -2018, and conclude that SPAC investors do reasonably well, earning an annual return of 9.3%. More impressively, the downside protection on these deals put a floor on their losses, with even the worst deal generating a positive return (0.51%). In contrast, if you look at returns to SPAC investors in the weeks and months after a SPAC merger, the results are not edifying:

Source: Klaussner, Ohlrogge and Ruan (2021)

Put simply, no matter which measure of returns you look at, and over almost every time period, investors in SPAC-merged companies lose money. It is true that repeat sponsors do better than first-time SPAC sponsors, at least in the near term (three months), but the magic fades quickly thereafter. Finally, the median returns are much worse than the average, because of a few outsized winners, and that may explain part of the allure, is that these winner stories get told and retold to attach new investors. If there is a cautionary note in these findings, it is for investors who invest in SPAC-merged companies, after the deal is consummated, since it looks like for many of these companies, prices peak on the day of the deal, and wear down in the months after, partly because the hype fades and partly because SPAC warrant conversions continue, upping share count and the dilution drag on value per share.

- Owners of issuing companies: There are three levels at which you can assess whether companies that plan to go public benefit from the SPAC phenomenon. The first is in whether some of the companies that used SPACs to go public would have been unable or unwilling to do so, in their absence. The second is whether the companies that did go public, using SPACs, generate higher proceeds than they would have received, if they have followed the traditional IPO route. While it is almost impossible to test either proposition, I would assume that given the number of companies that have gone public using SPACs, some of them would have chosen to stay private, if their only option had been to use the banker-run process. I would also assume that at least some of the companies that were able to take advantage of the speedier SPAC process to generate higher prices, by timing their issuances better. The third is how the company's stock price does in the period after going public, and it is here that I think SPACs have not served private companies well. By creating layers of dilution, first to sponsors, next when raising capital from PIPEs and finally from the warrants granted along the way, they impose burdens on the stock that are difficult for it to overcome. I don't think that too many private companies would be happy with the post-merger performance that SPAC-merged companies posted in the table above, since it poisons the well for both future stock issuances, as well as for owners (VCs, founders) planning to cash out later in the game.

The bottom line is that SPACs, at least as constructed now, are games loaded in favor of the sponsors. There are some SPAC investors who are canny players at this game, usually cashing out at the time the deal is announced and using warrants to augment their returns, but those SPAC investors who stay on as shareholders in the merged company find themselves holding a loser's hand. Finally, while there are issuing companies that may be able to go public because of SPACs and collect higher proceeds, the dilution inherent in the process acts as an anchor dragging and holding down stock prices in the aftermarket. While there are some who are pushing for the SEC to ban or constrain SPACs, the problem, as I see it, is not that there is insufficient regulation, but that investors in SPACs who are sometimes too trusting of and too generous to big name sponsors, and too lazy to do their own homework. In fact, there is a path to redemption for SPACs and it will require the following changes:

- Reduce the sponsor subsidy: The sponsor subsidy in most SPACs creates a hole that is too deep for investors to dig out of, even if the SPAC merger goes smoothly and is at the right price, since there isn't enough surplus in this process to cover a 20% dilution or more.

- Align SPAC sponsor and SPAC investor interests: There are too many places where sponsor and shareholder interests diverge in the SPAC structure. Since sponsors get to keep their subsidy only if the deal goes through, there is an incentive now to push deals through, even if it is not in the best interests of shareholders, and then dressing it up enough to get it approved.

- Level the playing field on disclosures/capital: You cannot have two sets of rules on forecasts and business stories, a tighter one for traditional IPOs and a loose one for SPAC IPOs. Rather than tighten the rules on what SPACs can spin as stories, I would suggest loosening the rules for traditional IPOs. To the response that this could create misleading disclosure, I would suggest trusting investors to make their own judgments. To be honest, I would take three pages of pie-in-the-sky forecasts from a company going public, and decide what to believe and what not to, than twenty pages of mind numbing and utterly useless risk warnings (which you get in every prospectus today). On the fairness front, I also think that the restrictions on capital raising for companies that go the direct listing route are also outmoded, and may need to be removed or eased. Given that it has the fewest encumbrances and intermediaries, without this handicap, the direct listing approach to going public may very well beat out both the banker-based and SPAC IPO approaches.

- Reduce deal underwriting costs: I am having a difficult time understanding why the deal fees on a SPAC deal are as high as they are (5-6%), especially if the sponsors are being compensated for finding the right target and negotiating the best price. Who is being paid these deal fees, and what exactly are the services that are being provided in return?

In an ironic twist, the SPAC process, designed to disrupt the traditional IPO, may be seeing the beginnings of a disruption of its own. Bill Ackman's Pershing Square Tontine SPAC, created in 2020, pointed to one possible variation, where the sponsors reduced their upfront subsidy and increased their holdings of out-of-the-money warrants, giving them a greater stake in getting a good deal done. Last week, that SPAC announced that it would be acquiring a 10% stake of Universal Music for $4 billion from Vivendi, and that shareholders in the company would get shares in Universal as well as the rights to invest in a SPARC (a special purpose acquisition rights company), with the intent of raising capital, in the event of a future deal. (Unlike a SPAC, which raises money first and then looks for a deal, in a SPARC, the capital raise occurs only in the event of a deal.)

Conclusion

As markets change, both in terms of investor mix and information sharing, it is not surprising that corporate finance and investing practices, that were accepted as the status quo until recently, have come under scrutiny. The banker-centric IPO process has had a good run, but it is showing its age, and it is good that alternative approaches are emerging. The problems for these alternatives is that going public, no matter which approach you use, is much easier when you are in a hot market, as we are in right now. That said, IPO markets though go through cold periods, where investor reception turns frigid and the number of public offerings drops off, and it is then that the weaknesses and failures of approaches become most visible. Neither direct listings nor SPACs have gone through that trial by fire yet, but if history is a guide, it will come sooner, rather than later.

Related: Inflation and Investing: False Alarm or Fair Warning?