Written by: Lucas Detor and James McManus

The post-pandemic recovery in commercial air travel is well underway, and a rapidly growing global middle class means the skies will only get more crowded. But aircraft supply is barely keeping up as manufacturers struggle to make up for past capacity cuts and overcome supply chain challenges.

Over the past 50 years, commercial aviation traffic, as measured by revenue passenger miles, has grown at nearly twice the rate of global gross domestic product—despite the 9/11 terrorist attacks, global financial crisis and COVID-19 pandemic.

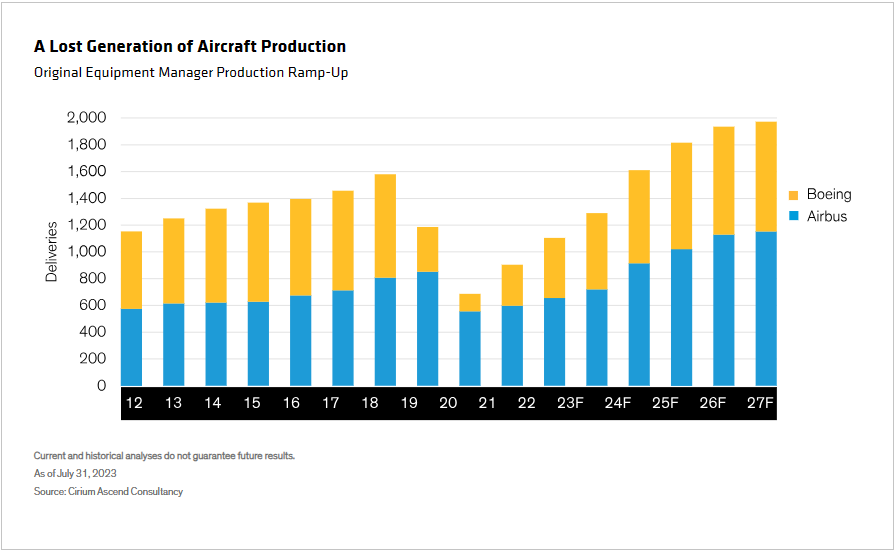

And the International Air Transport Association (IATA) projects that traffic will grow by 3.4% annually through 2040. Meeting that demand will require a lot of planes—particularly now that production cuts that accelerated during the pandemic have resulted in a “lost generation” of almost 3,000 aircraft (Display).

Cleared for Takeoff

Taken together, the air-traffic recovery and structural supply constraints create a compelling private credit opportunity to invest in in-service aircraft and lease them to airlines in need of more capacity. We believe this strategy has the potential to produce strong long-term cash flows and provide an uncorrelated source of return.

It also provides investors in private credit strategies with long-term exposure to global growth. Aircraft leasing is especially common among emerging-market (EM) air carriers in Asia and the Middle East—regions where rising income levels provide the means and motivation to travel. We think this demand dynamic could last until the global population peaks, which could take 80 years. EM populations will also boom, making them prime candidates for upgrading transportation infrastructure.

Investing in Aircraft, Not Airlines

Operating an airline is something of a feast-or-famine business. Carriers have limited control of their unit costs, due in part to fluctuating fuel prices and a high fixed-cost base. And over the last five years alone, the industry has endured a global pandemic, which bankrupted several airlines, and geopolitical conflict. Put simply, it isn’t easy for carriers to make money.

We think owning a global portfolio of airplanes—hard assets with intrinsic value—and leasing them to carriers in need is an effective way to get aviation exposure not tied so closely to individual airlines. If one carrier struggles, the plane can be leased to a different one, because planes are fairly standardized. Think of it as investing in aircraft rather than the companies that fly them.

It’s a scalable opportunity, and risk can be segmented across aircraft type and vintage as well as capital structure. A 2022 report by IATA and McKinsey found that the simple average return on invested capital from aircraft leasing has been higher—and steadier—than airline returns in every year but one between 2012 and 2021. And that one year? It wasn’t a pandemic year.

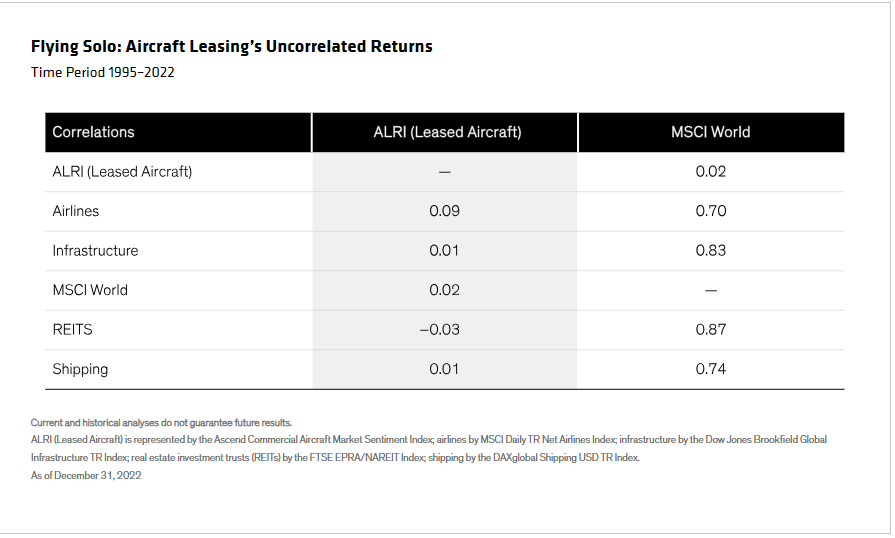

The distinction between leasing an aircraft and operating an airline also helps explain why aircraft leasing has shown a very low correlation to related strategies and assets (Display), including those dedicated to infrastructure investments, real estate investment trusts and even listed commercial airlines.

We believe mixing an aircraft leasing strategy into a diversified portfolio has the potential to mitigate downside risk when times get tough.

Financing Opportunities Throughout the Cycle

There are fewer than 30,000 commercial jets in operation today, and about half are leased. Most have a 30-year life, though frequent upgrades to newer, more fuel-efficient planes keep turnover high and average lease life shorter than the plane’s life. This provides opportunities for aircraft leasing throughout the market cycle.

Leasing helps airlines stay flexible and responsive to changing supply and demand, which also means aircraft leasing stays active throughout the market cycle. When demand is low, as it was during the pandemic, lessors can enter sale-leaseback arrangements, acquiring planes from airlines in need of liquidity and then leasing them back for regular use.

When conditions improve and travel demand rebounds, large public lessors often sell midlife and older planes to modernize their fleets—a requirement for maintaining their investment-grade ratings.

These planes—typically narrow body aircraft that fly shorter routes—are the workhorses of most fleets and can offer attractive value for investors. Focusing on midlife aircraft that still have a long useful life ahead can help create opportunities and reduce risk.

Unlike the newest generation of aircraft, midlife aircraft are a proven technology. And they can be monetized in multiple ways when the time comes to sell, including via trade, sale and conversion to freighter. Finally, midlife aircraft typically produce ample cash flow relative to cost. Together these factors can make for a favorable risk-return scenario.

Reaping the Benefits Requires Managing the Risks

Of course, executing these strategies successfully requires robust sourcing and strong management capabilities; owning and leasing aircraft isn’t easy. Doing these things well typically comes down to capabilities and experience.

Experience can also help when it comes to managing risk. For example, certain factors could reduce travel demand and dampen the outlook for aviation leasing. Escalation of regional conflicts in Ukraine and the Middle East would raise fuel prices and reduce travel demand, so it’s important for aircraft lessors to actively manage regional exposure. And certainly, another global pandemic and similar quarantine measures could halt or greatly curtail travel.

From a big-picture perspective, though, we think aircraft are a compelling and long-run avenue for capturing economic growth. As the middle class grows, so will travel demand. In our view, contractual aviation leases, with their strong cash flow and income potential, may help investors make the most of it.

Related: The Importance of Governance: Evidence from the Proxy