Yes. We are in a stock market bubble. But what if conventional methods of examining market cycles miss a crucial point? While we often talk about parts of cycles (bull or bear), exploring the full-market cycle may provide another way to look at long-term bubble cycles.

The Speculative Cycle

Charles Kindleberger suggested that speculative manias typically commence with a “displacement,” which excites speculative interest. The displacement may come from either an entirely new investment object (IPO) or increased profitability of established investments.

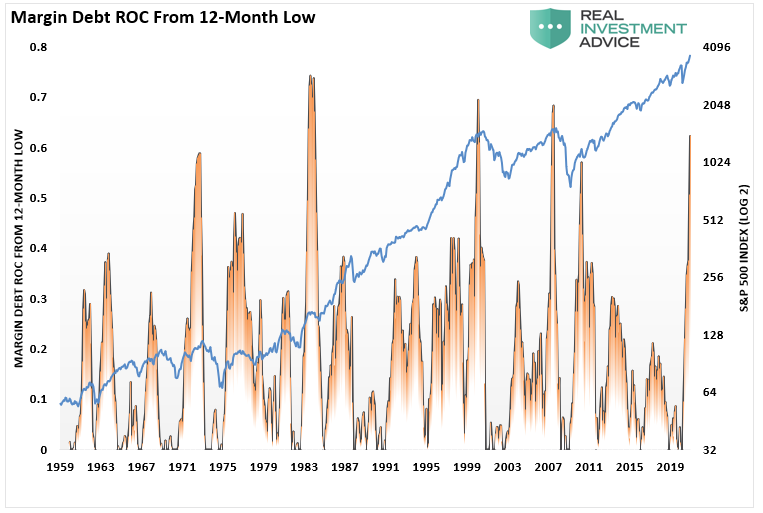

The speculation gets reinforced by a “positive feedback” loop from rising prices. Such ultimately induces “inexperienced investors” to enter the market. As the positive feedback loop continues and the “euphoria” increases, retail investors then begin to “leverage” their risk in the market as “rationality” weakens.

During the mania, speculation becomes more diffused and spreads to different asset classes. New companies get floated to take advantage of the euphoria, and investors leverage their gains using derivatives, stock loans, and leveraged instruments.

As the mania leads to complacency, fraud and manipulation enter the marketplace. Eventually, the market crashes and speculators get wiped out. The Government and Regulators react by passing new laws and legislations to ensure the previous events never happen again.

Wash, Rinse, and Repeat.

The Full Market Cycle

“‘Even apart from the instability due to speculation, there is the instability due to the characteristic of human nature that a large proportion of our positive activities depend on spontaneous optimism rather than mathematical expectations, whether moral or hedonistic or economic. Most, probably, of our decisions to do something positive, the full consequences of which will be drawn out over many days to come, can only be taken as the result of animal spirits-a spontaneous urge to action rather than inaction, and not as the outcome of a weighted average of quantitative benefits multiplied by quantitative probabilities.’ – John Maynard Keynes

Keynes’s idea of “animal spirits,” which were awakened by consecutive rounds of monetary stimulus on a global scale, has enticed investors to believe that all risks of a market cycle completion have gotten removed.

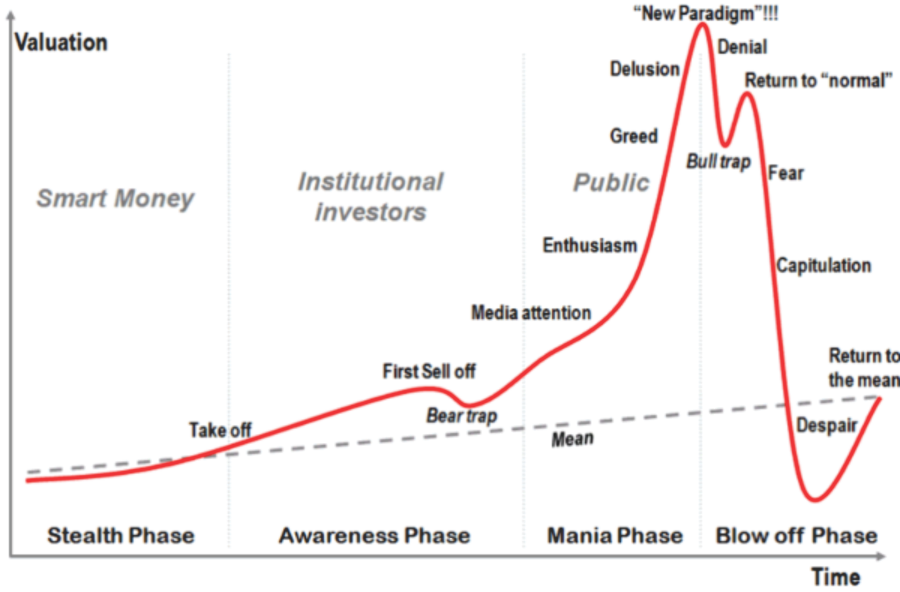

The exuberance from the financial media and many pundits reminded me of this chart on the full-market cycle.

I have often discussed the importance of full-market cycles.

However, what you should note is that when it comes to investing, what has separated long-term “investing success” stories is when those individuals started their journey.

- Warren Buffett started in 1942 and acquired Berkshire Hathaway in 1964.

- Paul Tudor Jones launched his hedge fund in 1980

- Peter Lynch managed the Fidelity Magellan Fund starting in 1977

- Jack Bogle launched Vanguard in 1975

The list goes on, but you get the idea. Much of these investing greats’ success came from catching the beginning of a bull cycle with low valuations and high forward returns.

The Full Cycle

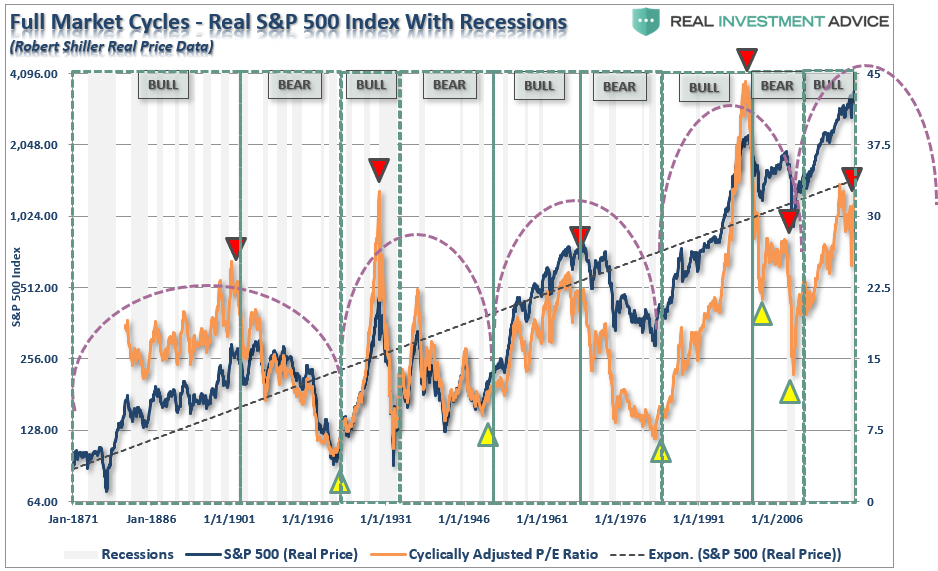

As shown above, most of the investing returns came in just 4 of the 8-major market cycles since 1871. Every other period yielded a return that lost out to inflation during that time frame.

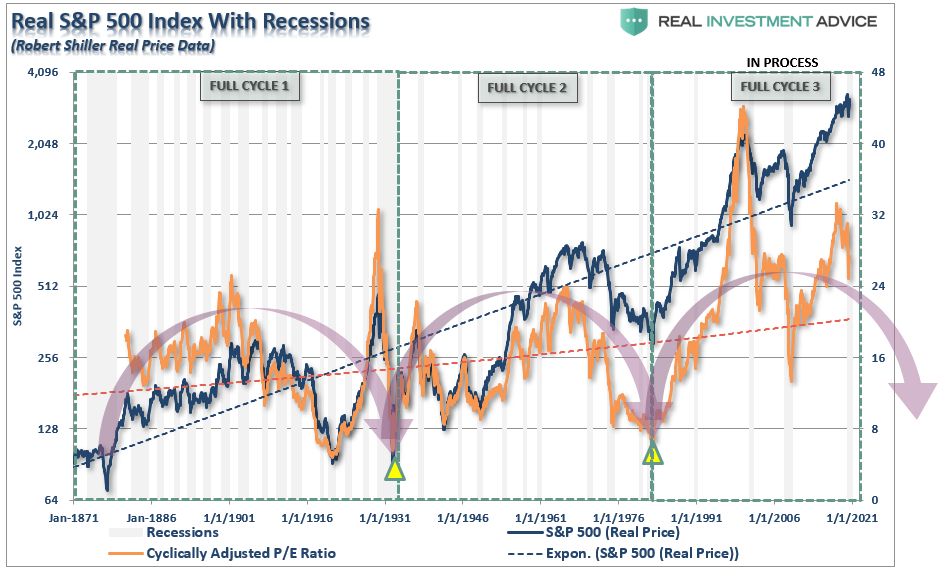

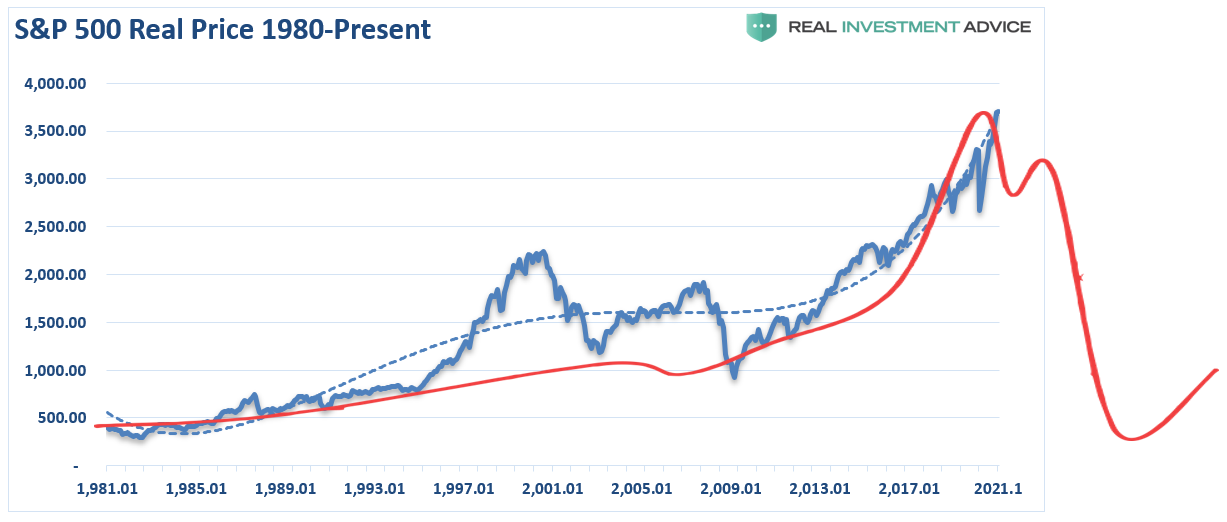

However, if we adjust our view to look at each full-cycle period as two parts, bull and bear, the dynamics change. Such suggests the cycle that began in 1980 has not yet finished.

Notice in the chart above the CAPE (cyclically adjusted P/E ratio) reverted well below the long-term in both prior full-market cycles. While valuations did, very briefly, dip below the long-term trend in 2008-2009, they have not reverted to levels either low or long enough to form the fundamental and psychological underpinnings seen at the beginning of the last two full-market cycles.

The 80’s Secular Bull Is Still Intact

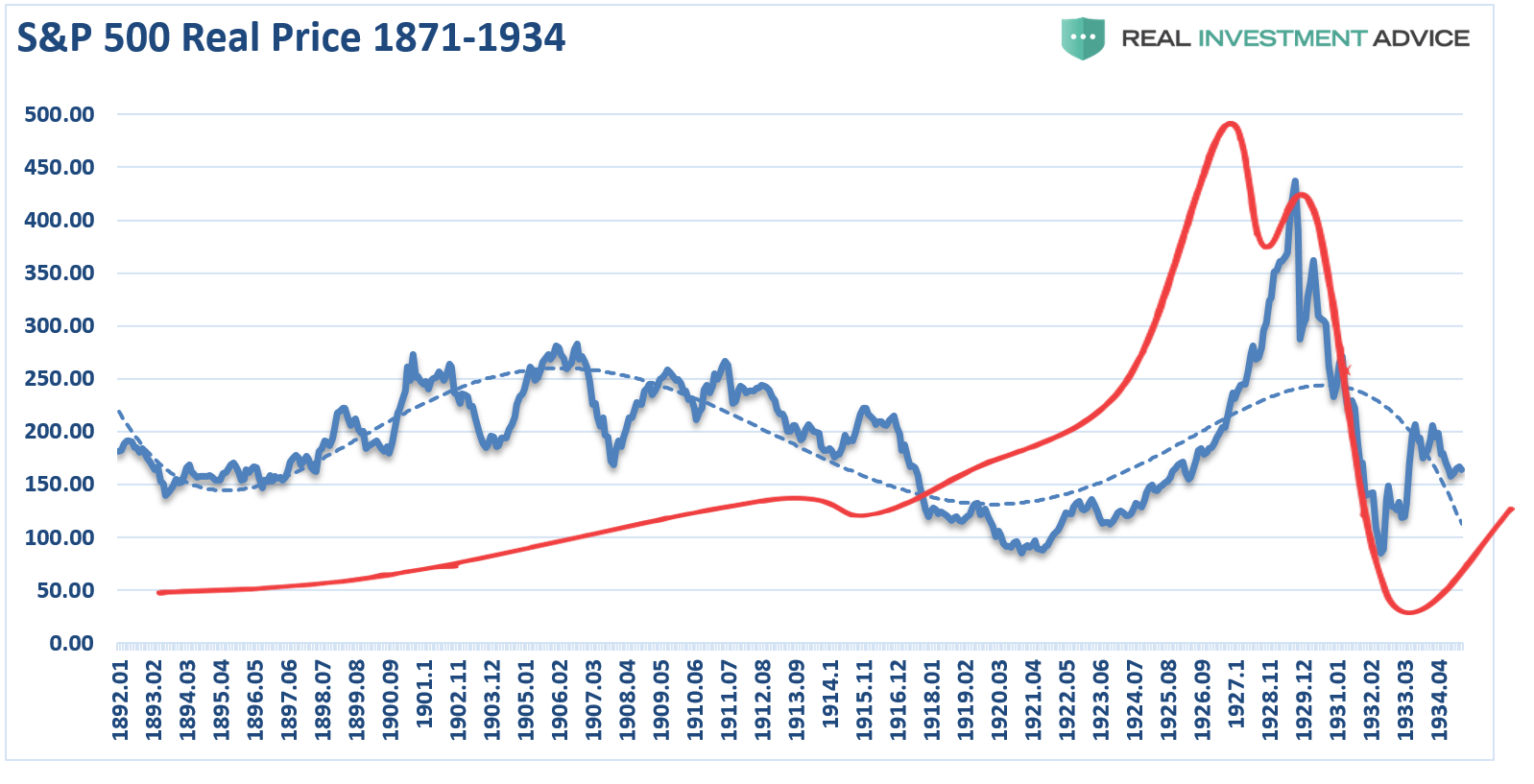

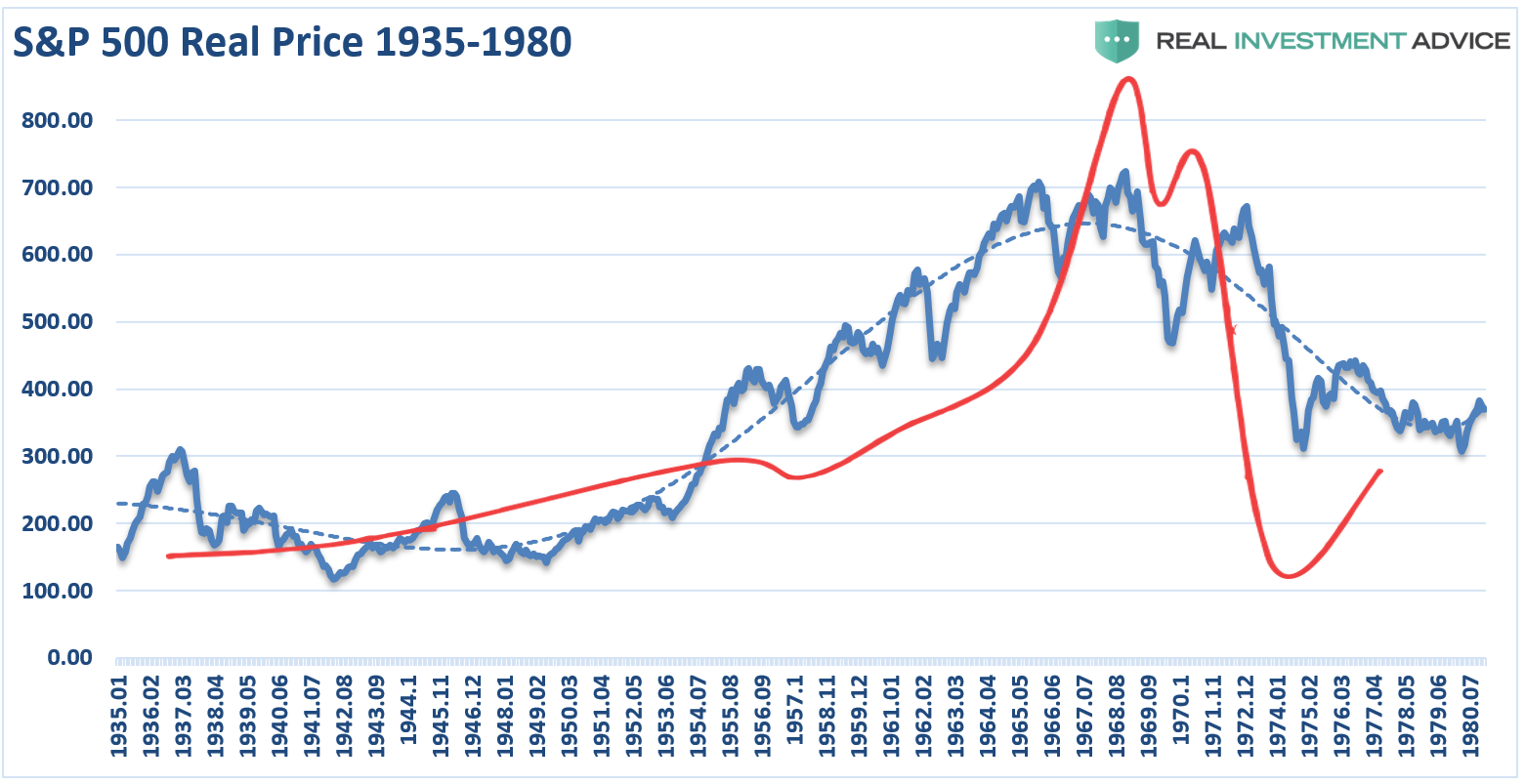

From that basis and historical time frames, I have created the following thought experiment of examining the psychological cycle overlaid on each of the three full-cycle periods in the market.

The first full-market cycle lasted 63-years from 1871 through 1934. This period ended with the crash of 1929 and the beginning of the “Great Depression.”

The second full-market cycle lasted 45-years from 1935-1980. This cycle ended with the demise of the “Nifty-Fifty” stocks and the “Black Bear Market” of 1974. While that crash was not as economically devastating as 1929, it significantly impaired investor psychology.

Notably, during both previous full-market cycles, the vast majority of gains made during the first half of the process got lost during the second half.

If history is any guide, is this what investors should be expecting in the future?

Halfway Through

The current cycle is only 40-years in the making, which is younger than both previous full market cycles. Given markets are trading at the 2nd highest valuation levels in history, corporate and consumers heavily leveraged, with economic growth rates running near historical lows, it is worth considering forward returns over the next decade.

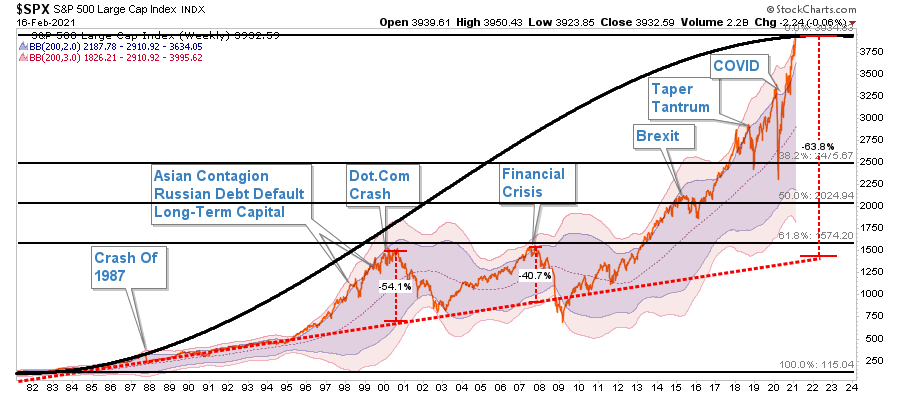

The idea the “bull market,” which begin in 1980, is still intact is not a new one. As shown below, a chart from 1980 suggests the same.

The long-term bullish trend line remains, and the cycle-oscillator is only half-way through a long-term cycle. Furthermore, on a Fibonacci-retracement basis, a 61.8% retracement would currently intersect with the long-term bullish trend-line around 1600, suggesting the next downturn could indeed be a nasty one. But again, this is only based on the assumption the long-term full market cycle has not yet finished.

I am NOT suggesting this is the case. Such is just a thought-experiment about the potential outcome from the collision of weak economics, high levels of debt, valuations, and “irrational exuberance.”

Yes, this time could entirely be different.

It just never has been before.

Something To Consider

I am not making a “bearish prognostication,” I am only presenting a view to ponder.

Historically, all market crashes have been the result of things unrelated to valuation levels. Issues such as liquidity, government actions, monetary policy mistakes, recessions, or inflationary spikes are the culprits that trigger the “reversion in sentiment.”

Notably, the “bubbles” and “busts” are never the same.

I previously quoted Bob Bronson on this point:

“It can be most reasonably assumed that markets are efficient enough that every bubble is significantly different than the previous one. A new bubble will always be different from the previous one(s). Such is since investors will only bid prices to extreme overvaluation levels if they are sure it is not repeating what led to the previous bubbles. Comparing the current extreme overvaluation to the dotcom is intellectually silly.

I would argue that when comparisons to previous bubbles become most popular, it’s a reliable timing marker of the top in a current bubble. As an analogy, no matter how thoroughly a fatal car crash is studied, there will still be other fatal car crashes. Such is true even if we avoid all previous accident-causing mistakes.”

Comparing the current market to any previous period in the market is rather pointless. The current market is not like 1995, 1999, or 2007? Valuations, economics, drivers, etc., are all different from one cycle to the next.

Most importantly, however, the financial markets always adapt to the cause of the previous “fatal crash.”

Unfortunately, that adaptation won’t prevent the next one.

Yes, this time is different.

“Like all bubbles, it ends when the money runs out.” – Andy Kessler

Understanding The Risk

Over the next several weeks, or even months, the markets can extend the current deviations from the long-term mean even further. But that is the nature of every bull market peak and bubble throughout history as the seeming impervious advance lures the last of the stock market “holdouts” back into the markets.

As Vitaliy Katsenelson once wrote:

“Our goal is to win a war, and to do that we may need to lose a few battles in the interim. Yes, we want to make money, but it is even more important not to lose it.”

I wholeheartedly agree with that statement, which is why we remain invested but hedged within our portfolios currently.

Unfortunately, most investors have very little understanding of markets’ dynamics and how prices are “ultimately bound by the laws of physics.” While prices can certainly seem to defy the law of gravity in the short-term, the subsequent reversion from extremes has repeatedly led to catastrophic losses for investors who disregard the risk.

Just remember, in the market, there is no such thing as “bulls” or “bears.”

There are only those who “succeed” in reaching their investing goals and those that “fail.”

No Bull Or Bear

Sure, this time could be different. However, as Ben Graham said in 1959:

“‘The more it changes, the more it’s the same thing.’ I have always thought this motto applied to the stock market better than anywhere else. Now the really important part of the proverb is the phrase, ‘the more it changes.’

The economic world has changed radically and will change even more. Most people think now that the essential nature of the stock market has been undergoing a corresponding change. But if my cliché is sound, then the stock market will continue to be essentially what it always was in the past, a place where a big bull market is inevitably followed by a big bear market.

In other words, a place where today’s free lunches are paid for doubly tomorrow. In the light of recent experience, I think the present level of the stock market is an extremely dangerous one.”

He is right. Of course, things are no different now than they were then.

Pay attention to the market. The action this year is very reminiscent of previous market topping processes. Tops are hard to identify during the process as “change happens slowly.” The mainstream media, economists, and Wall Street will dismiss pickup in volatility as only a corrective process. But when the topping process completes, it will seem as if the change occurred “all at once.”

The same media that told you “not to worry” will now tell you “no one could have seen it coming.”

But such has been the same ending of every bear market in history.

Just make sure you aren’t part of the story when it occurs.