Written by: James C. Fallon and Christopher Zani | MFS

In brief

- The underperformance of low volatility strategies compared to capitalization-weighted indices has some wondering whether the style has lost its effectiveness, but the performance of volatility is consistent with other market cycles.

- Our defensive, low volatility strategy seeks to avoid the most volatile stocks and is not driven solely by a small cohort of the least volatile.

- In what can be projected as a higher rate environment, it is reasonable to believe the prospects for low volatility are more positive than they are negative.

During the past decade, low volatility investing has evolved from an academic factor risk premium to an understanding of company fundamentals influenced by market cycles. The evidence demonstrates that historically, low-risk stocks have outperformed high-risk ones, although their performance during the 2020 global pandemic suggests the pattern is not consistent.

In this paper, we will review:

1) The underperformance of the low volatility premium during the Covid melt-up and demonstrate that long term investors can continue to benefit from allocating to lower risk stocks.

2) How our approach to low volatility investing at MFS is uniquely situated to capture the low volatility anomaly.

3) The performance of low volatility stocks through the lens of market cycles and offer our perspective on the outlook for these stocks.

Performance of low volatility during the Covid melt-up

While low volatility stocks have performed remarkably well over the last decade, the three-year period from 2018 through 2020 has demonstrated the factor’s inability to keep up with the cap-weighted index, and low volatility stocks did not provide the expected downside protection during the COVID selloff of 2020, leaving investors wondering whether the factor is indeed broken. We begin by looking at low volatility stocks within market cycles, then provide insight on the recent market selloff and compare the fundamentals of baskets of low volatility stocks with baskets of high volatility ones.

Low volatility and market cycles

The underperformance of low volatility strategies compared to broader market, capitalization-weighted indices in 2020 might lead investors to wonder whether the low volatility style has lost its effectiveness and is in fact a flawed, if trendy, approach. However, when comparing the recent performance of low volatility stocks with their performance in prior cycles, we see that the early stages of cycles favor riskier assets. In these environments, low volatility stocks typically underperform, and often by wide margins compared to high volatility. The 2020 underperformance is not as extreme as what we saw in the early months of 2009 at the end of the global financial crisis, which was the start of a cycle that saw low volatility outperforming in its later phases.

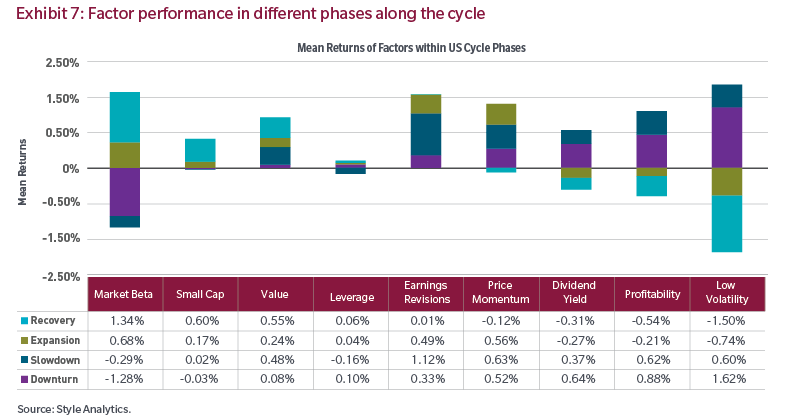

The MFS paper "Factor Dynamics Through the Cycle" (February 2021. Morrison, Stocks, Bryant) explains factor behavior during the four phases of a typical cycle: recovery, expansion, slowdown, downturn. The paper shows how factors such as market beta and small caps tend to drive the early stages of cycles while factors such as profitability and low volatility don’t emerge as drivers until the late stages. Based on the authors’ analysis of US market cycles since 1989, we don’t expect low volatility to be a characteristic of stocks that outperform in the early stages of the cycle.

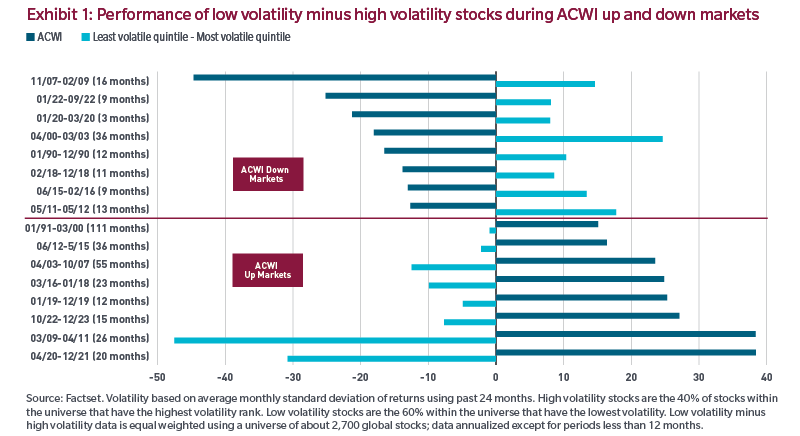

Exhibit 1 compares the returns of up markets (early cycle) to those of down markets (late cycle) from worst to best periods since 1991. For each down market (upper part of illustration), low volatility outperforms high volatility. Conversely, during up markets (lower part of illustration), high volatility typically outperforms, and sometimes dramatically.

The last period on the right demonstrates that during the most recent up market (starting in April 2020), higher volatility stocks have had exceptionally strong relative performance compared to lower volatility ones. The illustration shows, for investors interested in low volatility strategies, what to expect during early-cycle periods and what to expect in later ones. It is worth noting that up markets can last several years while down markets are often shorter but just as steep in magnitude. The up market periods below had an average duration of 40 months while the down markets experienced lasted for an average of 14 months.

What happened during February and March of 2020?

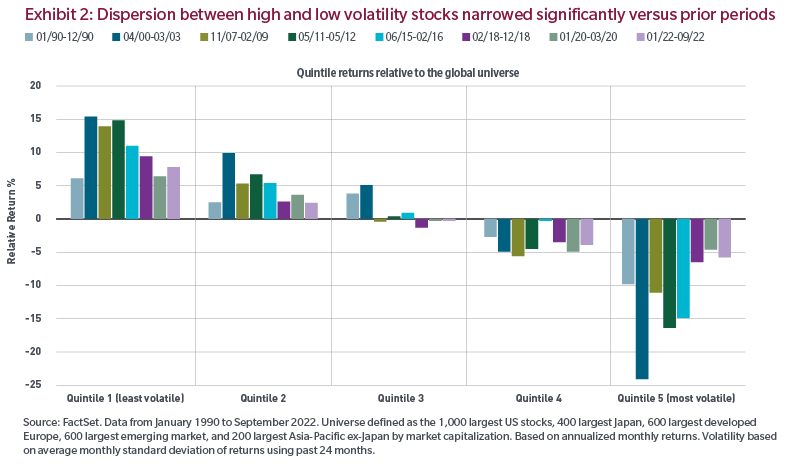

During market selloffs over the past 30 years, lower risk stocks have tended to outperform their higher risk counterparts as investors have rotated away from market risk. This can be seen in Exhibit 2 below, which portrays the six major market drawdowns that have occurred since January 1990. While owning lower-risk stocks in a selloff is typically a prudent way to protect capital, unlikely market events can sometimes reduce the benefit of owning these stocks in these situations. These "left tail" events illustrate investors’ tendency to flee the market entirely after a scare, regardless of the risk profile of the stock.

In Exhibit 2 we provide perspective on these types of events. The first time this can be observed is during the Savings and Loan crisis of the early 1990s. The last time was the COVID selloff of early 2020. In both these occurrences, investors exited the marketplace without rotating into lower-risk stocks. High-risk stocks sold off as expected, but what made these periods unique was that lower-beta stocks did not provide as much protection as their betas would suggest in a phenomenon we call “beta compression,” observed in the differences between the returns of low risk (left hand) and high risk (right hand) stocks. We discussed this recently in the MFS paper "Beta Compression" (January 2021. Fallon, Zani, Delaney). These market environments are extremely unusual and driven largely by unique economic circumstances.

We believe this compressed spread is not reflective of typical selloffs, and we do not think we will see this dynamic turn into a consistent trend. While low volatility stocks have demonstrated the ability to mitigate risk, there have been periods, such as 1990 and 2020, in which indiscriminate selling has led to beta compression that has limited the low volatility stock portfolio’s active return. These observations suggest that the initial findings of low volatility stocks may continue to hold as the cycle unfolds.

Are low volatility stocks still expensive on a fundamental basis?

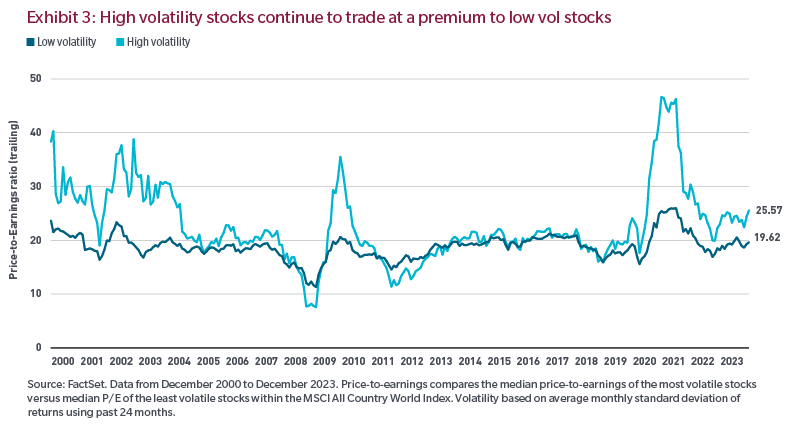

The strong demand for these high-performing low volatility strategies over the past decade has often meant investors have paid a valuation premium to access them, a trend that has altered course in recent years. As illustrated in Exhibit 3, high volatility stocks continue to trade at a valuation premium to low volatility ones on a price-to-trailing-earnings basis. Based on this observation, there is a potential “margin of safety” via the valuation premium of lower risk stocks.

MFS approach to low volatility investing

Investor assets allocated to low volatility strategies has grown substantially over the past decade across many types of implementations, including passive, purely statistical and fundamental. We recognize that despite being labeled as a mathematical anomaly or phenomenon, the outperformance of low volatility stocks is explained through fundamental company drivers that develop over the course of the cycle. Let’s take a closer look at our investment philosophy and in doing so explain why an overreliance on a risk model or passive approach can be flawed.

Not all low volatility is the same

Why should we expect these patterns to repeat going forward? After all, volatility is simply a measurement of return patterns that does not tell us anything about the long-term potential of the underlying businesses. Furthermore, the outperformance of low volatility stocks has not only been labeled an anomaly but also contradicts the popular business theory idea of no pain, no gain, or the misconception that investors need to allocate further out along the risk spectrum in order to achieve higher returns. What evidence do we have to confirm that this "low volatility anomaly" will persist?

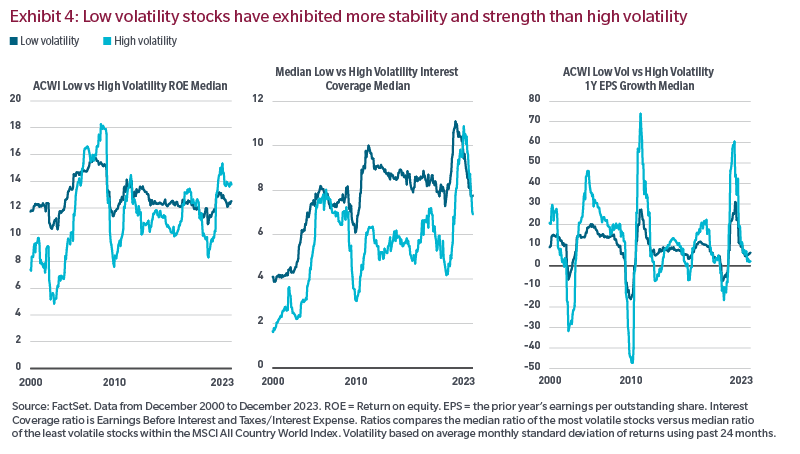

When we examine the fundamental composition of the low volatility investible universe, we can see why the anomaly is in fact not an anomaly at all. Fundamental drivers of low versus high volatility stocks demonstrate a distinction between the more stable, durable companies of the low volatility universe and the more cyclical exposure of higher volatility stocks. In Exhibit 4 we compare the most volatile 40% of stocks in the MSCI All Country World Index (those we have identified as the more-cyclical stocks likely to underperform over the long run) with the least volatile 60% of stocks. The data show that lower volatility stocks tend to have more stable and less cyclical return-on-equity and earnings growth as well as stronger interest coverage.

In short, there are long-term winners and losers among companies despite shorter trends that contribute to market extremes and sentiment. We believe that over the long run and through market cycles, stronger fundamental characteristics help to identify those winners. More stable fundamentals tend to characterize the low volatility universe.

This does not mean that that universe does not include its share of weaker companies and investment ideas, but it does underline that it is prudent to avoid companies that are likely to underperform and expose investors to sharp market drawdowns.

Why avoid high volatility stocks?

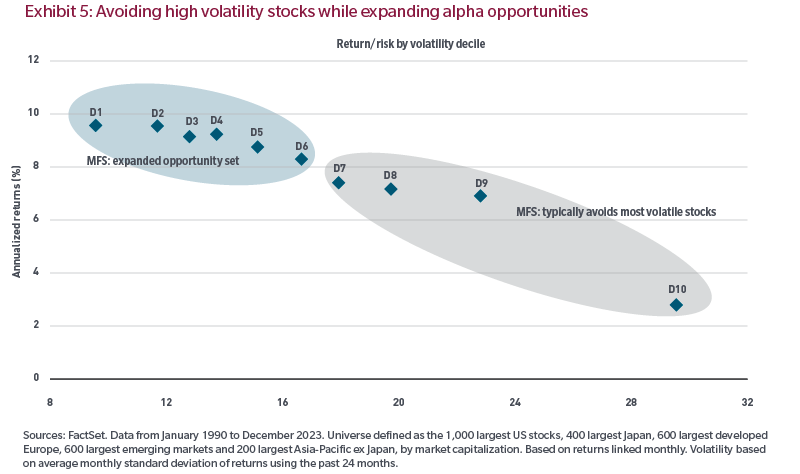

Investors face a myriad of choices when looking for low volatility managers. Some strategies seek to closely mirror a minimum volatility index while others seek to create the lowest-risk portfolio. At MFS we take an alternative approach based on the scatter plot in Exhibit 5, which shows the equal-weighted annualized return (y axis) of a global universe of investable stocks when deciled by 24-month volatility (x axis).

Our investment philosophy is rooted in the fact that the essential element of a defensive, low volatility strategy is to avoid the most volatile stocks but is not driven solely by the least volatile tail of 10% to 20% of stocks. This subtle, but important distinction, allows for greater freedom to build client portfolios with higher exposure to both our fundamental and quantitative inputs while still reducing absolute volatility overall. It also facilitates a broad approach to diversifying across robust investment ideas while avoiding investment trends that can hurt clients in the long run, such as herding or crowding behavior.

Shortcomings of risk models

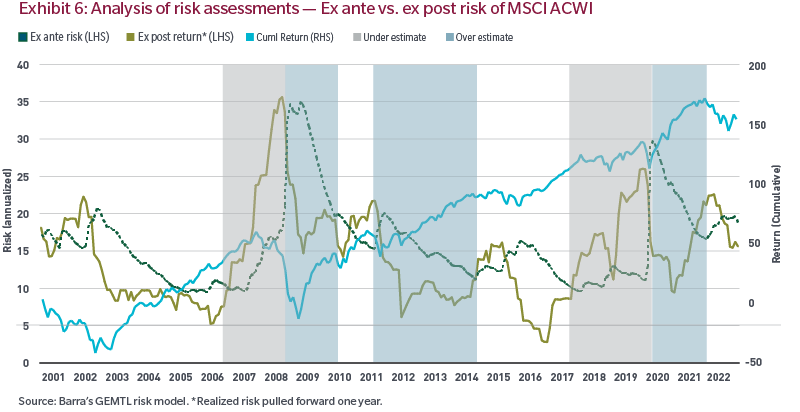

Low volatility strategies strive to be “less risky” than the capitalization-weighted benchmark, and often this means optimizing to an ex ante (projected) risk level below the benchmark. While we recognize an ex ante risk approach is one part of the overall makeup of a strategy, we do not solely focus on it as the singular definition of ‘risk’, as risk models tend to over- or understate risk based on what has happened recently. Risk does have a high degree of auto-correlation, and therefore the best estimate of current risk is what most recently occurred. This estimate is primarily based on historic risk, but we know that this will not provide an accurate estimate when we encounter market inflections driven by unexpected shocks.

Exhibit 6 helps us visualize this dynamic as it has played out over the past 20 years in global markets. It plots the ex-ante risk of the MSCI ACWI index (LHS) along with the ex post realized forward 12-month standard deviation of returns (LHS). The job of a risk model is to demonstrate what future risks may exist; therefore, we compare future realized risks to the current assessments of risk. Before large market corrections or shocks, risk models tend to underestimate risk. This is seen in the grey shaded areas that show low ex ante risk versus high ex post (realized) risk. We also see that in the light blue–shaded areas that after large market shocks risk models will often overcorrect risk estimates (projected risk higher than realized risk), essentially closing the barn door after the horses have bolted.

We recognize that risk models are a useful tool in risk assessment and portfolio construction but not the only tool, as the fragility of the covariance matrix makes anticipating risk difficult. As such, we take care to not simply optimize to an ex ante absolute volatility target but to instead view portfolio risks through multiple lenses such as upside-downside capture and Sortino ratio (standard deviation of negative returns).

Drawbacks of passive implementations

The debate over active versus passive investing in the capitalization-weighted space has lasted for quite some time. The same philosophical differences exist within low volatility. The main index provider continues to be MSCI with its suite of “minimum volatility” products. The starting point for their construction is the relevant capitalization-weighted index. Then an optimization is run utilizing Barra’s GEMTL model (for global products) to minimize portfolio covariance subject to a country and sector constraint of 5%.

As we review the methodology, we see three potential shortcomings when weighting the benefits of a passive implementation over an active.

The first is simply the starting point: The backbone of the strategy is the relevant cap-weighted index. Although the optimization process will not choose intrinsically highly volatile stocks, it is possible for stocks with higher volatility to make their way into the minimum volatility index simply because of a negative covariance.

The second shortcoming of passive is the overreliance on backward-looking risk models, which tend to over- and under-estimate risks at different points of the economic cycle. We believe a more wholistic approach to risk, looking at not only a stock’s co-movement but also its fundamental profile, is better than looking through a purely statistical lens.

The third problem with passive is the rebalance frequency. Risk is a dynamic and fluid proposition which can change very frequently. Active managers who have the insight and latitude to reposition portfolios before large-scale idiosyncratic events happen can dampen longer-term volatility rather than holding onto these names until a predetermined rebalance date occurs. A strategy that rebalances once or twice a year can leave investors exposed to weak investments for extended periods.

What does the future hold for low volatility investing?

As we look forward, it is important to better understand the return profile of investing in lower-risk stocks. Low volatility in its purest form is a market premia, such as value, growth or small cap, and as with any market premia, the relative performance is dependent on where in the economic cycle you are. In our piece titled “Factor Dynamics Through the Cycle,” we define four distinct market cycles based on OECD Leading Economic Indicators. As Exhibit 7 shows, the worst time to own low volatility as a premia is during the recovery and expansion phases. This is intuitive, as recovery phases tend to be all about high risk and expansion tends to be focused more on industrial cyclicality tied to material and energy companies. It also puts into the context the performance of low volatility strategies in 2020, when investors wondered whether the style was broken. We would argue that no, it was not broken. It was simply behaving as expected during the part of the cycle where the premia does not pay off well.

The next logical question is how do we expect low volatility to perform in the future? We again refer to our cycle piece as a framework for understanding potential outcomes. Coming out of the COVID crisis with extreme measures implemented by fiscal and monetary authorities, the move into the expansionary phase occurred quickly. Since then the impact of high inflation and slowing global economic activity has resulted in a move through the slowdown phase and into downturn. Low volatility stocks have performed well in this environment as they have typically done in the past. Should the downturn phase be of an extended duration the prospects for low volatility should continue to be more positive than they are negative.

Why should investors be considering a low volatility allocation today?

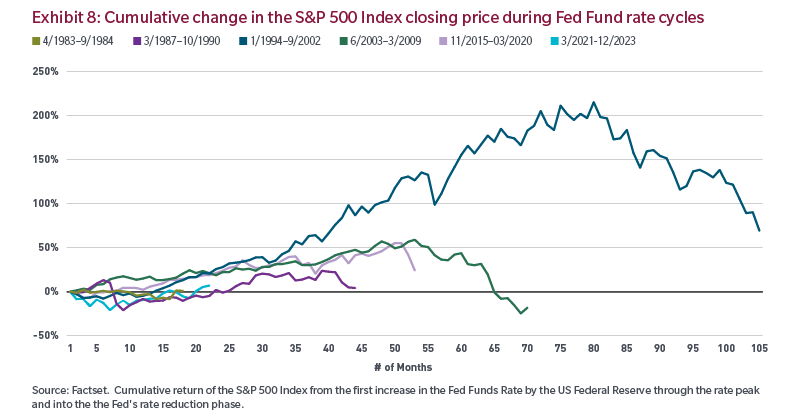

Cycles during which the Federal Reserve raises the Fed Funds rate by at least 300 basis points, followed by a period of sharply reducing the rate, has been met with disruptive periods for equity markets. As the chart below shows, four of the past five periods experienced sharp market sell-offs during the later stages of these cycles: typically closer to the period in which the Fed reduces the rates. The fifth period was relatively shorter but also featured volatility. An important observation as the chart shows, is that timing these cycles can be difficult, and cycles have lasted for years. Consider that this cycle was preceded by exceptionally low rates historically as well as exceptionally strong stimulus policies, and inflation that has been higher than any of these periods. Stabilizing an equity allocation via low volatility can help to address some of the uncertainty during what will likely be a volatile environment for equities.

Conclusion

The underperformance of low volatility stocks in 2020 may have investors questioning a current or potential allocation, but we believe our analysis shows the investment rationale for low volatility is still intact.

- There is more to risk than just standard deviation of returns and understanding that the more stable and less cyclical fundamentals of low volatility stocks can be a powerful element in reducing the impact of down markets.

- Low volatility stocks are trading at more compelling valuations than high volatility ones, which suggests there is an attractive entry point for this style of investing.

- The days of central bank’s zero interest rate policies appear to be behind us, leaving markets with uncertainty and volatility. Stocks with negative earnings and higher volatility, which did well in a low rate environment, will have a difficult time going forward.

We believe that actively managed low volatility strategies can go a long way toward minimizing volatility and offering better investor outcomes. Applying fundamental and quantitative research to identify and diversify across a set of appropriate investment ideas — as well as using time-proven criteria such as valuation discipline and quality — makes active management best suited to fighting volatile markets.