Inflation is back on investors’ minds lately, and some may be wondering how to position their portfolios to confront this potential new scourge. It’s been many years since skyrocketing prices have been a real concern, but there are a number of inflationary pressures in play right now, both near-term and long-term, that investors should have on their radars.

Policymakers tell us that there’s nothing to worry about. Earlier this week, Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell tried to downplay inflation concerns, testifying before Congress that “prices remain particularly soft” even for those sectors that were hardest hit by the pandemic.

Powell’s not wrong—if we’re measuring inflation by the government’s preferred gauge, the consumer price index (CPI). According to the CPI, prices rose only 1.4% year-over-year in January, well below the Fed’s target of 2%. For the past 10 years, the monthly reading has averaged a tepid 1.7%.

But others are starting to question the accuracy of the CPI. I’ve written about this topic before. I think most Americans could list a number of real-life examples of prices for everyday things climbing much faster than 2% over the past year.

Near-Term Inflation: Food Prices and Shipping Costs

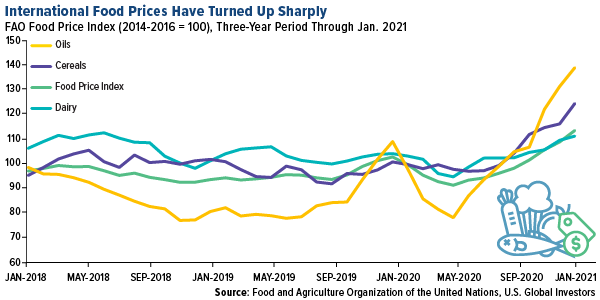

Take food prices. According to the United Nation’s FAO Food Price Index, a basket of food commodities rose for the eighth straight month in January, registering its highest monthly average since July 2014. Prices for vegetable oils in particular have surged to multiyear highs, due in large part to excessive rainfall in Indonesia and Malaysia that has impacted palm oil production.

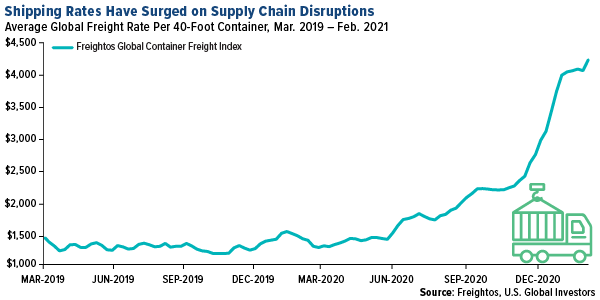

Exacerbating food prices is the shocking increase in international shipping costs. Supply chain disruptions such as container box shortages and port congestion have pushed the cost of shipping a 40-foot container above $4,000, up from $1,500 a year ago. Freight rates from the Far East to Europe have surged the most, increasing 10 to 15 times in some cases.

In a press release dated February 17, the Global Shippers’ Alliance wrote that shippers worldwide are “furious at the chaotic shipping market and the lack of mechanisms to resolve it.”

Of course, these inflationary pressures are strictly near-term risks and unlikely to persist. The sky-high freight rates are “unsustainable” and should “moderate in the medium term once supply chain disruptions ease, as the industry is highly competitive,” writes Fitch Ratings.

Structural Long-Term Inflation: Fiscal Spending and Wage Hikes

Inflated food prices and shipping costs are likely to resolve themselves. The same can’t be said about government policy, which we believe is a precursor to change.

Tomorrow the House is scheduled to vote on President Joe Biden’s massive $1.9 trillion coronavirus relief package, and then it’s on to the Senate. If passed, Biden is expected to sign it before mid-March, making it the second multi-trillion-dollar package in the past 12 months. That’s not including the $900 billion bill signed into law in December 2020.

PIMCO economists Libby Cantrill and Tiffany Wilding forecast that the added stimulus, including $1,400 checks for qualifying Americans, could push U.S. economic growth to between 7.0% and 7.5% this year, “levels not seen since the early 1980s and, before that, the mid-1960s.”

The downside to this is that we could see inflation not seen since the 1970s. To be clear, Cantrill and Wilding don’t seem to believe this is likely, but “inflation could exceed central banks’ targets eventually.”

We’re still waiting to hear whether the bill will include a federal minimum wage hike to $15 an hour by 2025, which would most certainly contribute to consumer price appreciation. This was one of the key findings of a 2017 study by economists at the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston. The team found that a 10% increase in the minimum wage in a metropolitan area “is associated with an overall inflation rate that is 8 basis points higher” compared to other areas that didn’t hike wages.

Fifteen dollars an hour represents a 107% increase from the current minimum wage. Using the Boston Fed’s calculations, that would add nearly a full percentage point in annual inflation, a not-insignificant amount.

Time to Rotate into Hard Assets?

Taking all of this into account, it may be time for investors to rotate into hard assets such as metals and other commodities.

Commodity prices are already on the rise thanks to near-zero interest rates, the economic recovery from the pandemic and now the likelihood of additional rescue packages. The Bloomberg Commodity Index, which tracks 23 raw materials, is at its highest level since March 2013 as hedge funds and other institutional investors bet that unprecedented monetary and fiscal stimulus will continue for some time. This week, Bank of England policymaker Gertjan Vlieghe said that “normal” rates from before the financial crisis may not return “in my lifetime.”

Born in 1971, Mr. Vlieghe is 49 years old.

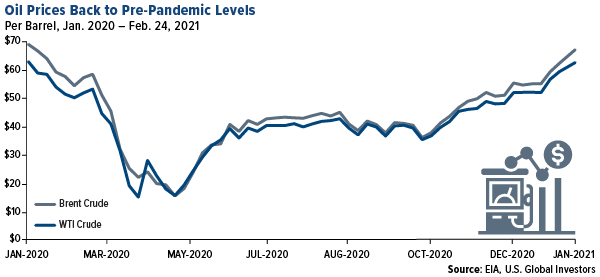

Many commodities have been hitting 52-week highs. Oil is back above $60, and analysts at Goldman Sachs estimate $75 by summer.

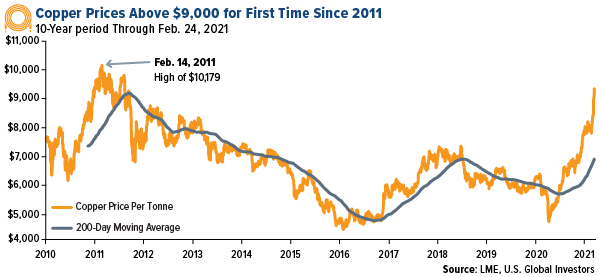

Copper, meanwhile, has shot above $9,000 per tonne for the first time in nine years and could easily test the previous all-time high set in February 2011.

Earlier this month, the price of silver briefly touched $30 an ounce in intraday trading, but I can see it going much higher as governments push for greater renewable energy generation.

I believe, in fact, that we’re at the cusp of a new commodities supercycle, and there’s still time to start participating.

Related: The Case Against Inflation