Written by: New York Life Investments

Did you know that the debt ceiling has been raised 78 times since 1960? That’s right – this U.S. political process has, on average, taken hold more than once per year in the last 73 years.

That said, not every debt ceiling debate is as dramatic as the one we are experiencing now, and this process has implications for the economy and markets.

Here are five things we think investors should know about the debt ceiling, as the potential U.S. default date moves closer.

1. The most likely scenario is that a debt ceiling disaster will be avoided.

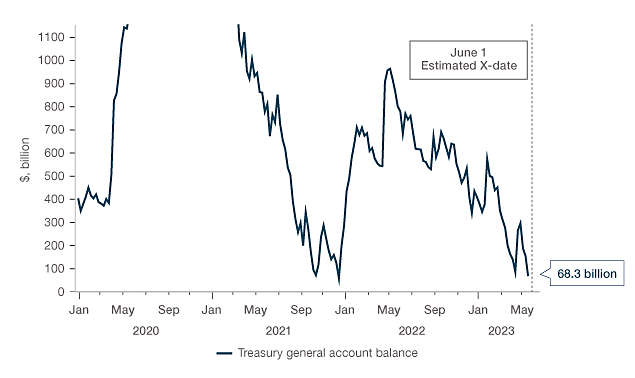

The deadline for lifting the U.S. debt ceiling is moving closer. U.S. Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen has said that the x-date – the date when the U.S. government might default if the limit on federal borrowing is not lifted – could be as early as June 1.

Policymakers have moved to a conversation about how the debt ceiling will be resolved rather than whether it will be resolved. This should be good news. While both parties may feel there is political benefit to the standoff, there is unlikely to be any political benefit from a debt ceiling disaster. Whether the debt ceiling is raised temporarily or for a longer period, we expect some resolution to be met.

2. U.S. debt is a bedrock of the global financial system. A default scenario is therefore very difficult to position around.

It’s worth saying again: despite the drama, U.S. probably won’t default on its debt.

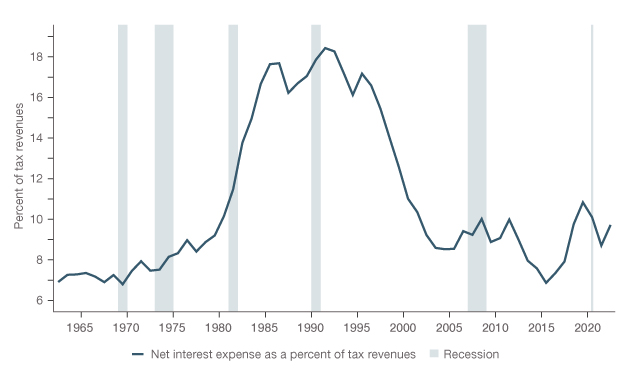

While they’ve never done it before, the Treasury has said it can prioritize payments to debt holders. Since U.S. tax revenues are in a healthy position to cover interest expenses (see below), this means the Treasury could avoid an outright default for a bit even if we tip over the debt ceiling. As an aside, our research providers tell us that when interest costs as a percentage of tax revenues hit 15%, financial markets begin to impose discipline on policymakers.

But if the U.S. did default on its debt?

A U.S. Treasury default is one of those black swan risks that is so extreme it doesn’t pay to position around it. Treasuries are the credit-risk-free rate, the base for the whole financial system. Remember the phrase “too big to fail”? That’s an understatement for the U.S. Treasury market.

3. Still, there are costs to 11th hour brinkmanship.

While we expect disaster to be avoided, there are still costs to 11th-hour brinkmanship.

- Economic costs: Household and business confidence plummets and uncertainty about asset prices, borrowing costs, and economic activity amid a default or shutdown can make households and businesses reluctant to spend. Worse even, a debt ceiling fight this year would likely increase the effects of the economic slowdown and even pull forward recession timing.

- Financial market costs: In serious debt ceiling debacles, equities tend to fall while volatility and credit spreads rise. If the situation is dire, foreign investors may move capital out of the U.S., weakening the dollar. So, for investors, as tends to be the case when risk spikes, quality is king. Equities with valuations and earnings that are more resilient to higher yields may suit, like value equities; and on the fixed income side, this might be a vote in favor of investment grade corporate bonds.

- Reputational costs: In the 2011 debt ceiling fight, the U.S. credit rating agency Standard & Poor’s downgraded U.S. debt. Concerns about the full faith and credit of the U.S. government could lead to further downgrades. We believe this change could be significant. It takes decades to build up global market confidence; repeated policy mistakes could result in lower demand for U.S. assets, even if on the very margin, in the future.

4. Moving past the debt ceiling battle doesn’t clear investors from volatility.

Resolving the debt ceiling would take a major risk off the table for the global economy. It can be expected that many investors would view this to be bullish for markets.

However, there is still an important risk to that outcome. Once debt ceiling is risen, the U.S. Treasury would then refill its general account by selling Treasuries. This would draw down on overall liquidity as markets absorb the new debt. The equity market has tended to pullback as liquidity is drained from the economy, so the post-debt ceiling environment may be negative for equities.

5. Keep an eye on long-term U.S. debt sustainability

The debt ceiling battle is largely a political process relating to U.S. debts already incurred. However, there is reason for investors to pay more attention in the future about the long-term economic issue of debt sustainability. In short period of time, tailwinds for U.S. debt sustainability have turned to headwinds, putting this debate back on investors’ map.

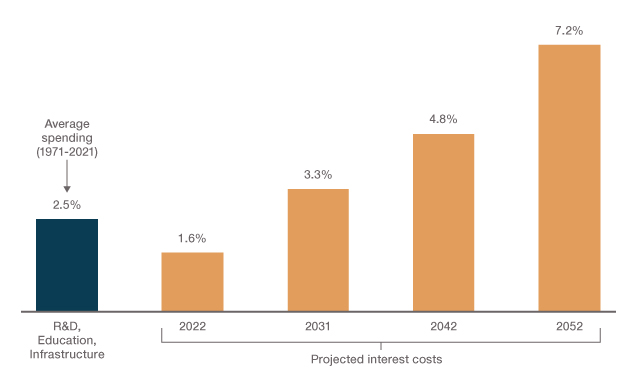

For one, debt servicing costs have gotten more expensive because “lower for longer” rates have moved higher, and fast. This is important not only because U.S. debt has gotten more expensive, but because that cost is likely to trigger real political concern. A key metric to track will be the government’s net interest expense as a percent of GDP. By 2052, net interest is expected to be nearly three times the total federal spending on research and development, education, and infrastructure:

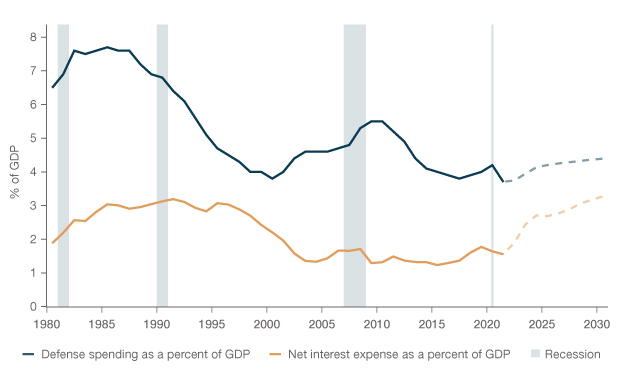

Think about that for a second. If hard lines aren’t drawn around further spending at that moment, then an interest burden approaching the size of the defense budget probably would. The chart below compares net interest and defense spending both as a percent of GDP and includes the Congressional Budget Office’s forecast through 2030.

For two, demand for U.S. Treasuries could be declining:

- Negative yielding debt surpassed $17T in 2019 and is now down to zero. As a result, many global buyers of U.S. bonds have other positive-yielding options.

- The Federal Reserve is selling Treasuries as a part of its quantitative tightening (QT) program.

- An increasingly competitive geopolitical landscape has some countries, including China, looking for different stores of wealth.

Declining demand, even amid steady supply, would put durable upward pressure on U.S. bond yields, all else equal. In other words, the U.S. might see an increase in its term premium – a seed change in global investing.

Related: Stock Markets Likely to Rally This Week on Fed Minutes, Caution Needed