Written by: John Lin and Samuel Chen

Beijing’s 2060 carbon neutral initiative will direct an investment cycle toward cleaner energy infrastructure. But first, supply-side reforms mean higher raw materials prices for consumers—and opportunities for equity investors in both renewable energy stocks and dirtier industries that are transitioning to a sustainable business model.

China’s plans to reach peak carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions by 2030 and carbon neutrality by 2060 are both ambitious targets. Based on the buoyant share price performance of industrial and material industries, it appears that China’s green initiatives are well-advertised and communicated to the market.

While developed countries outline climate agreements, China’s participation matters most. The country is the world’s largest greenhouse gas emitter, releasing twice the amount of the US and accounting for about a third of total global emissions.

Supply-Side Reform 2.0

To reach the country’s carbon targets, Beijing has implemented its second iteration of supply-side reform. China is replaying a similar strategy from five years earlier, when policy efforts aimed to cap excessive commodity production in high-polluting areas.

China’s war on pollution isn’t new, but its weapon of choice is. In the opening salvo to combat greenhouse gases, commodity producing regions have again taken the initial hit. The industrial city of Tangshan, which produces 15% of the country’s steel and 8% of the world’s, has removed between a third and half of its capacity (Display). Inner Mongolia has already suspended all new projects for ferro-alloys, aluminum, alumina and polysilicon until at least 2025.

The moves mark an escalation in a broader campaign to curb excessive carbon emissions. Job losses are imminent as factories close, highlighting the political challenges Beijing faces as it seeks to maintain employment and spur domestic consumption. But reducing industrial activity also simultaneously addresses other market-driven policies that Beijing hopes to enact.

Those measures include expediting state-owned-enterprises (SOE) reforms by consolidating less-profitable and higher-polluting entities. Managers at steel and aluminum SOEs have been tasked with reaching peak carbon emissions by 2025, five years earlier than the nation’s 2030 plan, reflecting the push for market-led change.

Higher Steel and Aluminum Prices

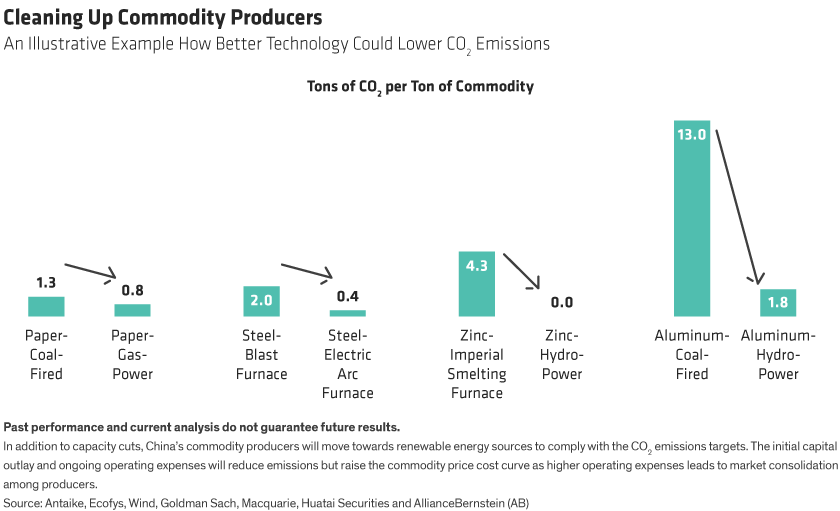

Since steel and aluminum production constitute 16% and 5% of China’s CO2 emissions, respectively, green investment upgrades will set precedents for how Beijing addresses other industries with high energy pollution. Long-term technology upgrades such as electric arc furnaces steel or hydro-power aluminum production emit much less carbon than current methods and offer viable commercial solutions over the medium and longer term (Display ).

The immediate transition is, however, more challenging, leaving production cuts as the most viable option available. Coupled with global demand recovery, restricted production of commodities from tighter emission standards is likely to fuel higher prices for global consumers, in our view.

Although rising commodity prices underscore the success of Beijing’s policies, there’s an irony: they may instigate other political challenges. Beijing has already warned against speculation in commodity prices as policymakers releases strategic reserves to ease rising input costs for downstream manufacturers. Yet, demand and supply fundamentals will only become more prominent over time, causing prices to climb higher.

As for steel, Chinese producers estimate that the cost to meet lower CO2 emission standards adds between RMB400 and RMB600 per ton. Chinese aluminum producers also face the prospects of higher costs should international carbon pricing standards go into effect.

Despite constituting only 5% of carbon emission in China, aluminum smelting is the most carbon-intensive process among industrial metals. As a comparison, steel production in China generates 1.5 to 1.8 tons of CO2 per ton of blast furnace-based production, while coal-based aluminum smelting emits 13 tons of CO2 per ton of aluminum ingot.

With a carbon-credit policy likely to take effect in 2022 for China’s aluminum industry, meeting local carbon pricing standards could add upward of RMB1,300 per ton to the aluminum cost base—about a 10% increase, and four times higher under a proposed carbon border tax in Europe where carbon credits are currently priced at €55 per ton.

Given the higher cost structures, we believe smaller producers will likely struggle, creating an opportunity for larger steel and aluminum producers to build out their market share. China’s four largest steelmakers together command 22% of the national market, a fraction of its Asian neighbors and western counterparts, and we believe that the opportunity to capture incremental market share will serve as an immediate earnings catalyst.

China’s 2060 carbon neutral agenda is unfolding as investors become more ESG-minded. We believe that growing investor engagement with company management could help push dirtier companies to promote cleaner and more cost-efficient ways of doing business. In our view, China’s carbon-neutral plan will be an important impetus for steel companies to set aggressive carbon emission reduction targets and invest in more renewable energy sources to lower green energy costs.

While curbing industrial production will be a key feature of China’s Supply-Side Reform 2.0, we expect an uneven policy implementation, as Beijing balances the economic recovery with its environmental needs. Central bankers will closely monitor the progress, as the potential increase in commodity prices would likely boost inflation pressure.

The ongoing cycle of manufacturing upgrades will feed demand for renewable and clean energy infrastructure, particularly in solar and wind generation. But active fund managers can develop green investment strategies that go beyond the obvious, deploying capital earlier in the policy cycle by targeting traditionally heavy carbon polluters where the initial cleanup will take place.

This might sound like an unorthodox approach to environmentally focused investing. But in our view, attractively valued companies poised to improve business fundamentals and minimize their carbon footprints can be a surprising source of return potential as China’s carbon-neutral plan gains traction.