Not all inflation is created equal. Peter Boockvar, CIO at Bleakley Advisory Group, has his finger on the economy’s pulse. And for the last year or so, he’s felt an inflationary heartbeat.

Peter, who is the author of The Boock Report, in which he flash-analyzes the latest economic data in handy bite-size multiple emails per day, makes an important distinction between goods inflation and services inflation.

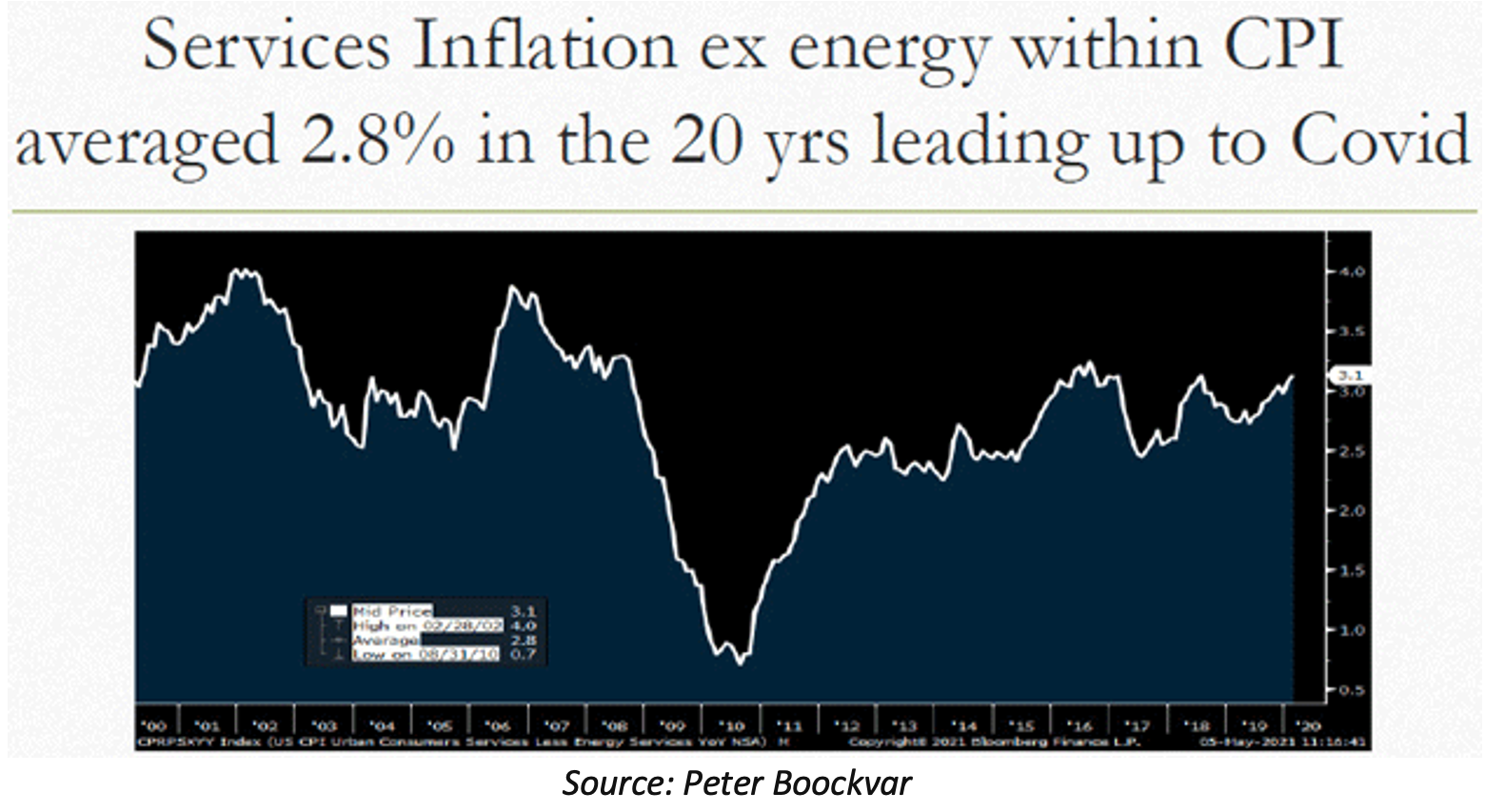

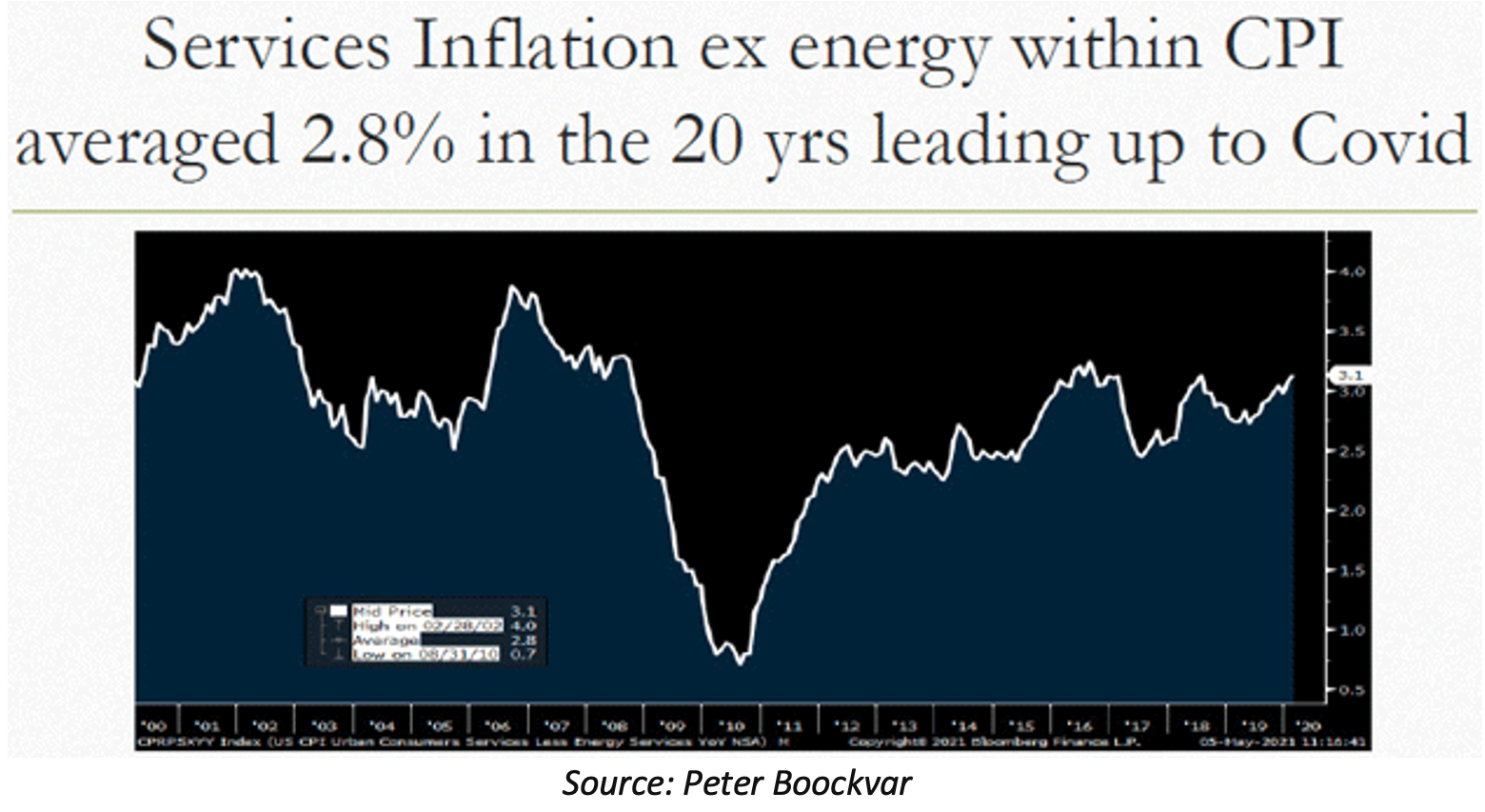

At Mauldin Economics' 2021 Strategic Investment Conference in May, Peter explained that they have been behaving differently. Looking at services inflation (ex-energy) within the Consumer Price Index, he showed that it averaged around 2.8% in the 20-year period leading up to the pandemic.

These services are the non-tangible things you can’t put in your pocket but are nonetheless valuable: rent, healthcare, college tuition, insurance, entertainment, etc.

Usually, we expect their price to rise every year. Our only question is, by how much.

Peter’s data says the answer has been around 2.8% a year. Sometimes a bit more or less, but rarely flat and never negative.

Take away the Great Recession, and the average is much higher. (Of course, your mileage may vary, depending on where you live.)

Goods, on the other hand, are the material objects and substances we buy in stores or have shipped to us: food, energy, cars, furniture, toys, lawnmowers, and so on. These prices have more variation than we usually see in services and often even go down.

If you never expected to see 0% inflation, now you have. But that’s only in goods—inflation in services pulled the full CPI higher.

How do we explain this discrepancy?

Two key factors are China and globalization. Goods inflation turned into stability, and often deflation, right about the time China joined the World Trade Organization (2001) and began exporting low-priced goods. But it wasn’t just China; globalized goods production really took off at that point.

The reversal of this strong disinflationary influence is one reason Peter expects inflation. It’s not entirely virus-driven; globalization has been slowing for other reasons. But the pandemic stepped on the brakes even harder.

In early 2020, when China basically shut down, we saw how vulnerable these ocean-spanning supply chains can be to events on the other side.

Meanwhile, staying home renewed our demand for various physical stuff. If you can’t go to concerts anymore, maybe you buy better home electronics—or a bigger home, which means you (or your contractor) buy more construction material, tools, etc.

Now we see shipping rates and container traffic rising sharply. This isn’t coincidence.

The global economy was optimized to deliver something else. Now has to suddenly satisfy new consumer preferences. That drives prices up.

Throw in the fact that many transportation companies went bankrupt over the past few years, and the supply of transportation companies all along the supply chain was reduced, and thus the prices paid to the survivors have increased.

If services inflation simply continues as it has, and goods inflation rises above the 0% level where it’s been for years, we should expect higher total inflation. But there’s reason to think services inflation will accelerate even more.

Buying services really means you’re buying some type of labor.

- In a restaurant, the food itself costs something, as does the building. But a large part of the bill, maybe most of it, is wages and tips for the cooks, bartenders, and waitstaff.

- In a hair salon or physician’s office, you pay mostly for professional time and skill. There is a close connection between services inflation and wage inflation.

Now look at what happened since last year.

The pandemic and its associated restrictions hit the service sector like a neutron bomb. The US government acted, appropriately, to help the millions rendered suddenly jobless. But as often happens, their methods weren’t targeted well. This, combined with the new hazards and hassles of in-person work during a pandemic, reduced the labor supply.

With the recovery now underway, employers need workers again and often have to pay higher wages to get them. That means even more service inflation, on top of the prior 2.8%+ annual growth.

Add in new goods inflation, and Peter doesn’t see how we could avoid a new inflationary cycle. The question is, how long will it last?

It looks like we are about to find out.

The Great Reset: The Collapse of the Biggest Bubble in History

New York Times best seller and renowned financial expert John Mauldin predicts an unprecedented financial crisis that could be triggered in the next five years. Most investors seem completely unaware of the relentless pressure that’s building right now. Learn more here.

Related: We Need Infrastructure Spending to Avoid Another Texas-Sized Mess