We have plenty of evidence that US debt will balloon to $50 trillion by 2030, maybe more. Many smart people conclude that, in the meantime, the federal debt isn’t a problem.

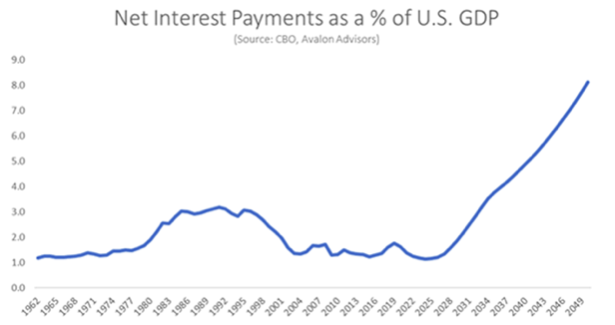

Looking at the numbers as a percent of GDP—and considering the CBO long-term forecasts out to 2050—Sam Rines, whom I greatly respect, writes this:

"In its latest round of projections, by far the most intriguing portion of the analysis related to the dynamics around the US federal debt load. The US debt load has increased dramatically due to the response to COVID, but the ability to service the US debt load is actually improving.

"Measured by interest payments on the debt relative to GDP, the US's fiscal situation is set to improve for the better part of the next decade. In fact, the figure is set to hit 1.1% in 2024. That is the lowest level of interest payments to GDP since at least the early 1960s.

"But that is where the projections become a bit less sanguine. Instead of going lower and remaining lower, interest payments then begin to rise, and continue to do so until the end of the projections in 2050.

"At 8.1%, the CBO is projecting interest payments on debt will grow to be more burdensome than Social Security as a percent of GDP. That is quite the assertion.

"But that is not the entirety of the story. There are a few assumptions made by the CBO that are rather suspect."

“Net Interest” is a significant and growing slice of federal spending. When your debt balance is measured in trillions, even tiny interest rate differences matter.

The obvious reason for increasing interest payments is a projection of rising borrowing costs. And that is where the CBO's analysis begins to show a few potential holes.

Sam thinks the federal debt will become a bigger problem when the economy improves and interest rates rise. I would argue much of that rise is already built into CBO’s high-side rate projections.

But there’s another wrinkle …

Based on CBO’s past record, their forecast for 3% ten-year yields in 2029 looks dubious to me. It has been well below that level for most of the last decade.

What would make rates rise that much? The only answer is some combination of a stronger economy and higher inflation.

The Fed recently revised its policy framework to “let” inflation run higher for longer. That’s the same Fed that's targeted 2% inflation for years now without success, at least on its own preferred benchmark. There is good reason for this.

The kind of broad inflation the Fed says it wants can’t happen unless the economy outstrips productive capacity for key goods and services.

Without that, general price levels simply can’t rise. Certain prices (rent and healthcare, for example) can rise enough to cause significant discomfort, but price weakness elsewhere keeps it from affecting the benchmarks too much.

Rising debt actively suppresses economic growth. Debt service prevents everyone (government, businesses, and households) from investing enough capital to generate long-term growth. This is why each new dollar of debt is producing less additional GDP.

We are borrowing to fund consumption instead of production.

It gets worse. The Fed thinks it can encourage growth by keeping interest rates low. But in fact, its “forward guidance” (pledging low rates long into the future) gives no one any reason to act now.

With no fear of rising rates as motivation, you might as well wait. Add our aging population and other demographic challenges, and there’s no reason to expect substantially higher GDP growth by 2030.

Some sectors will prosper, of course, as technology has in recent years. But others will suffer, leaving the macro growth outlook no better than it has been.

Even the CBO’s rosy scenarios show the economy spending the next two years digging out of the 2020 hole, then returning to the same sluggish growth as almost every year since 2005.

But if that’s what happens, we should be grateful.

The Great Reset: The Collapse of the Biggest Bubble in History

New York Times best seller and renowned financial expert John Mauldin predicts an unprecedented financial crisis that could be triggered in the next five years. Most investors seem completely unaware of the relentless pressure that’s building right now. Learn more here.

Related: What Happens When the Stumble-Through Economy Stalls?