Chinese President Xi Jinping is about to tell millions of government workers: “You’re fired.”

Reuters reported last week that China plans to lay off between five and six million state workers over the next two to three years, in an effort to curb overcapacity in what’s being described as “zombie companies”: those that are being kept alive on bank loans despite bleeding revenue. Close to two million of these layoffs will come from the coal industry alone.

The layoffs are part of a series of sweeping reforms that were announced ahead of the National People’s Congress (NPC) meeting. Every year, close to 3,000 Chinese officials and executives from all over the country convene in Beijing to develop and assess the status of the country’s Five-Year Plan. In response to worldwide demands that China manage its slowing economy better, President Xi Jinping this year has proposed what he calls “supply-side structural reform.”

And if that sounds a little like Reaganomics, that’s kind of the point.

Besides layoffs, Xi’s plan includes tax cuts, deregulation and reductions in state spending—economic policies you might expect to come from the desk of Reagan or Thatcher. We might also expect the results of these policies to be the same in China as in the U.S. and United Kingdom in the 1980s: a boom in entrepreneurship and innovation.

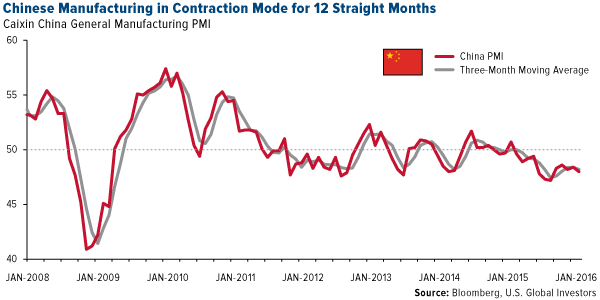

These reforms come at a crucial time for China, whose manufacturing sector has been in contraction mode for a year now as the country’s economy shifts toward domestic consumption. In February, China’s purchasing manager’s index (PMI) fell to 48.0 from 48.4 in January.

We closely follow government policy changes in China for a number of reasons. For one, its economy is the second largest in the world, and when based on purchasing power parity (PPP), its GDP is actuallythe largest, followed by the U.S., India and Japan. China’s economy, then, has a huge effect on the rest of the world, touching everything from commodities demand to consumption.

In 2015, total retail sales in China touched a record, surpassing 30 trillion renminbi, or about $4.2 trillion. By 2020, sales are expected to climb to $6.4 trillion, representing 50 percent growth in as little as five years. This growth will “roughly equal a market 1.3 times the size of Germany or the United Kingdom,” according to the World Economic Forum (WEF).

One of the main reasons for this surge in consumption is the staggering expansion of the country’s middle class. In October, Credit Suisse reported that, for the first time, the size of China’s middle class had exceeded that of America’s middle class, 109 million to 92 million. As incomes rise, so too does demand for durable and luxury goods, vehicles, air travel, energy and more.

But middle-income families aren’t the only ones growing in number. The WEF estimates that by 2020, upper-middle-income and affluent households will account for 30 percent of China’s urban households, up from only 7 percent in 2010.