Target date funds may be riskier than you think.

This is especially true as you get closer to retirement . But even if you are decades away from retirement, these funds may be taking on more risk than you are comfortable with.

There is a lot of misconception about target date funds. In a survey by the Securities and Exchange Commission , about 40% of respondents thought these funds were a safe investment for retirement. More alarmingly, 52% of target-date fund investors in the survey thought that target date funds guarantee retirement income.

They do nothing of the sort. The reality is that they simply offer a convenient way to invest in a diversified mix of stocks and bonds. And these investments can rise or fall, like any other investment in stocks and/or bonds.

What is the target date fund?

First a quick recap. A target date fund is basically a one-stop fund that individuals can invest in, and is most common in employer retirement plans like 401(k)s.

The key variable is your age, or rather, the year in which you want to retire — that’s your target date. Say you’re 40 years old now and anticipate retiring in about 25 years, i.e. in 2045. The target date fund you select for your plan would simply be the one with 2045 in its name. Or if you don’t make the selection, your employer may default you into the ‘appropriate’ target date fund.

That’s just about as much work you have to do with these things.

The fund then follows what is called a ‘glide path’, changing its mix of stocks and bonds every year until it hits the retirement target year. The idea is that bonds are less risky than stocks, and so the closer you get to retirement, larger the allocation to bonds.

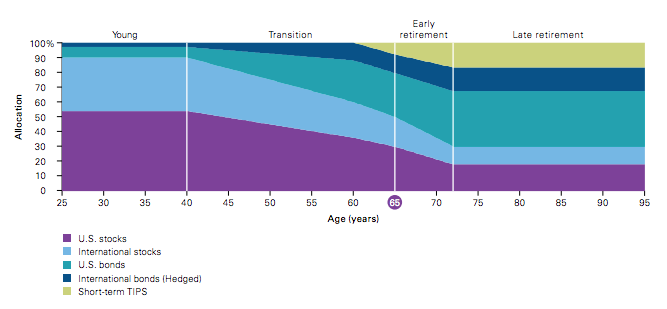

For example, here is Vanguard’s target date glide path:

Source: Vanguard

Source: VanguardWhat it shows is that up to age 40, your portfolio will have 90% stocks (domestic + international) and 10% bonds. Then it glides down, and at the retirement age of 65, the portfolio is about 52% stocks and 48% bonds.

The graph also shows that the allocation mix continues to glide even after retirement, whereas a lot of people believe it stops changing. At age 72 (the onset of ‘late retirement’) the Vanguard target date portfolio comprises 30% stocks and 70% bonds.

The advantage of using target-date funds is that you don’t have to worry about your stock-bond allocation and rebalancing to a new mix each year. The fund managers do all that work for you.

No wonder that target date funds have become increasingly popular. 2018 was the first year in which more than half of 401(k) participants put all their assets in a single target-date fund .

Note that this does not mean all these people don’t have diversified portfolios simply because 100 percent of their assets are in a single fund. On the contrary, as we saw above, each target date fund is fairly diversified across domestic/international stocks and bonds.

So what’s the problem?

Fees matter

The first thing is the fees.

If you’re lucky enough, the retirement plan offered by your employer offers Vanguard target date funds, which cost only about 0.12% per year i.e. $12 per year for every $10,000 invested.

The next largest providers are Fidelity and T. Rowe Price, and they charge more than four times what Vanguard charges. Fidelity’s and T. Rowe Prices’ target date funds have an average expense ratio of 0.61% and 0.72% , respectively. These are much closer to the industry average.

Fees can make a big difference to your eventual nest egg, as I wrote in a previous post .

However, the larger issue with target date funds is a risk.

How much risk do target date funds actually take?

Rather than showing you commonly used risk statistics (like volatility) I’ll do this differently.

I’ll illustrate the impact of recessions and crises on a portfolio that is similar to a target date fund. That way you get an idea of how these funds may have performed when trouble hit in the past.

With the obvious caveat that past performance is not indicative of future results.

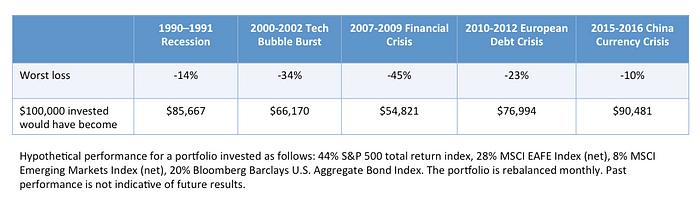

Let’s take the pre-retirement case first: an aggressive allocation, 80% stocks/20% bonds, mimicking the target date allocation mix when one is 15 or more years from retirement.

The table below shows the worst loss both as a percentage and in dollar terms (for a $100,000 investment portfolio) amid recessions and crises that occurred over the past 30 years*.

As you can see, an 80–20 stock-bond portfolios saw steep losses during several periods over the past thirty years. The portfolio would have lost almost half its value amid the Financial Crisis of 2007–2009. More recently during the European debt crisis — which seemed quite far away for American investors —the portfolio would have lost more than 20% of its value.

Even if you are decades away from retirement you have to ask yourself whether you are comfortable dealing with those kinds of losses.

In each case shown above, the market rebounded but that is hindsight knowledge. The question is whether you could have stuck with the investment during the crisis. Throwing in the towel at that moment and going to a more conservative portfolio would not be ideal.

Ultimately, the best investment portfolio is the one you can stick with rather than the one that is mathematically optimal.

Allocation mix can be critical close to or in retirement

The survey I quoted at the top of this piece was commissioned after the Financial Crisis of 2008. This was in response to the large drop in the value of several target-date funds that were close to their target year during that time.

Here’s the thing: a majority of target date fund owners in that survey believed less than 40% of the fund was invested in stocks at retirement. Numerous investors believe 100% of a target date fund is invested in cash at retirement.

This makes sense. Investors have the correct intuition that their portfolios should contain minimal risk at retirement, thus avoiding the possibility of a huge loss exactly when they need the money.

But that is far from reality.

As we saw from the Vanguard glide path, the allocation is closer to 50% stocks/50% bonds at retirement. Target date funds offered by Fidelity and T Rowe Price actually have a slightly higher allocation to stocks at the target year (about 55%).

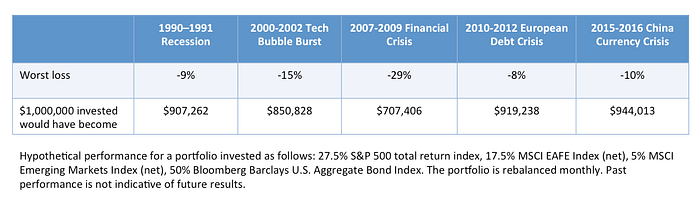

The table below illustrates the past performance of a hypothetical 50% stock, 50% bond portfolio amid the various crises. Instead of losses on a $100,000 investment, I use a $1,000,000 portfolio since we’re considering the retirement target year now.

The percentage losses are clearly less than what we saw earlier with a more aggressive portfolio. Yet the dollar losses on a large retirement portfolio are significant, and painful.

You‘d hardly want to see your $1 million nest egg fall to $919,000 (the European debt crisis) just as you are getting ready to retire. Let alone fall by almost $300,000 amid the Financial Crisis of 2007–2009.

That could easily translate into working a bunch of more years to make up for the losses. Something many soon-to-be retirees did over the past decade.

In summary:

Target-date funds can be a very convenient way to invest in a diversified portfolio without having to do too much work.

However, it is important to be aware of how these funds actually work, especially with respect to the amount of risk present in them.

Footnotes*Crisis Periods1990–1991 Recession: Jan 1990 to March 19912000–2002 Tech bubble burst: April 2000 to March 20032007–2009 Financial crisis: November 2007 to February 20092010–2012 European debt crisis: May 2010 to May 20122015–2016 China currency crisis: August 2015 to February 2016