A single line chart is keeping an awful lot of investors up at night: the US Treasury yield curve. It’s been flattening steadily since the end of 2016 and is nearly the flattest it’s been since 2007. We all remember what happened after that.What investors really worry about is the yield curve going beyond flat to inverted, with short-term rates higher than long-term rates. It hasn’t been lost on investors that inverted curves have correctly signaled the past seven US recessions.We don’t think a flattening curve should trigger insomnia. In fact, it could be a positive sign for stocks.

The Fed Isn’t Jamming On the Brakes….It’s Tapping Them

The gap between the 10-year US Treasury yield and the fed funds rate has fallen nearly a full percentage point, from 1.97% at the end of November 2016 to 1.04% as of June 30. But looking at why the yield curve is flattening is just as important as knowing that it is flattening.Typically, the curve pancakes when the Fed is trying to put the brakes on a runaway economy with inflation heating up. When that happens, investors worry that growth and inflation are about to slow, prompting them to flock to safe havens, like long-term bonds.That isn’t what’s happening this time. Sure, growth is strong and even topped 4% in the second quarter. But even though inflation is slowly rising, it doesn’t point to an overheated economy. In our view, the Fed isn’t trying to throw water on runaway growth—it’s taking advantage of a strong economy to return the fed funds rate to a more typical pre-crisis level.So, at the Fed-controlled short end of the curve, short-term rates are rising and are likely to continue going up. Just how much will likely depend on the economic data.The Long End of the Curve Is Key

Long-term rates are controlled by market forces, not central bankers. That’s why we try to be somewhat agnostic about where long-term rates are heading. A few months ago, the 10-year US Treasury yield was at 3.11% and the curve was relatively steep, leading many investors to think rates were on an express train to 3.50%. That didn’t happen.No one knows exactly why long-term rates aren’t rising along with the strong economy. Some believe ultralow rates in other developed markets are pushing investors into relatively high-yielding US Treasuries. Others blame the so-called Amazon effect— the growth of online salesmakes comparison shopping easier, helping push down prices. Or maybe it’s the heavy debt in the economy. Or the aging population. The bottom line: many investors seem to think long-term rates can’t rise very far.Related: A Flattening Yield Curve Gives Investors Another Trend to Worry AboutCould a Flat Curve Be Good?

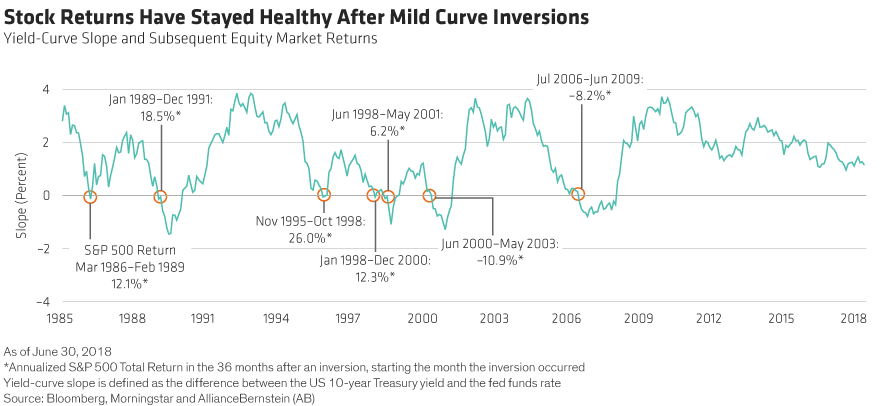

Whether long-term rates are stuck or not, we’re not convinced that the curve spells trouble for stocks.First, low long-term interest rates are good for stocks. They make earnings yields more attractive than government bond yields by comparison and allow companies to access very cheap debt to buy back stock and take other steps to enhance shareholder value.Second, the Fed has no interest in risking a recession by turning the yield curve upside down, so we think policymakers will be watching the 10-year yield closely. Some believe the Federal Reserve will hike six more times between now and the end of 2019. We believe that’s certainly possible, but only if growth stays strong and the 10-year yield rises appreciably as well.We believe the stock market can perform just fine with rates that high as long as growth stays steady. But all things equal, as equity investors, we’d rather see lower long-term rates. For us, the current aggressive flattening is a positive development for stock markets—not something to fear.Finally, even if the worst comes to pass and the curve rolls over, history shows that stocks can perform quite well for quite some time after this flip happens. During five mild inversions between 1986 and 2001, the stock market returned an average of 15% in the three years following the flip, starting the month the inversion occurred ( Display). The story could be different if a more dramatic inversion happens—think dot-com crisis and global financialcrisis. In these cases, stocks lost ground. But unless a 2008-style catastrophe is in the offing, a mild inversion isn’t likely to put a dent in equity portfoliosfor several years to come—if an inversion happens at all.

The story could be different if a more dramatic inversion happens—think dot-com crisis and global financialcrisis. In these cases, stocks lost ground. But unless a 2008-style catastrophe is in the offing, a mild inversion isn’t likely to put a dent in equity portfoliosfor several years to come—if an inversion happens at all.