Written by: Tiffany Wilding and Andrew Balls | PIMCO

The steepest interest-rate-hiking cycle in decades has set global economic activity on a course that remains difficult to map, making it especially important to respect risks and to look to build portfolios capable of performing well in a variety of conditions.

After major economies showed surprising resilience in 2023, we anticipate a downshift toward stagnation or mild contraction in 2024. The standout strength of the U.S. is likely to fade over our six- to 12-month cyclical horizon. Countries with more rate-sensitive markets will likely slow more markedly.

With inflation easing, developed market (DM) central banks have likely reached the end of their hiking cycles. That has shifted attention to the timing and pace of eventual rate cuts.

Historically, central banks do not tend to cut rates ahead of downturns, instead easing only after recessionary conditions appear and then delivering more cuts than markets anticipate. In the longer term, we continue to expect neutral policy rates to decline to levels similar to, or slightly above, those seen before the pandemic.

Echoing comments by Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell, we believe upside risks around inflation and downside risks to growth have become more symmetrical. However, recession risks remain elevated, in our view, due to stagnant supply and demand growth across DM. After a rally across many financial markets in late 2023, riskier assets appear priced for an economic soft landing and may be underestimating both upside and downside risks.

With attractive valuations and yields still near 15-year highs, fixed income markets can offer an array of opportunities with the potential to weather multiple macroeconomic scenarios.

In credit markets, we continue to favor U.S. agency mortgage-backed securities and other high quality assets backed by collateral, which offer both attractive yields and downside resiliency. The trend of banks stepping away from certain types of lending will likely persist and afford opportunities in asset-based and specialty finance in private markets.

We also see unusually appealing opportunities globally, with potential to outperform U.S. bonds based on greater downside economic risks. We are focused on more liquid DM markets given attractive yields, but will also look to find value in emerging market (EM) debt.

Cash yields remain elevated, but investors can miss out by sitting in cash too long. The bond market rally in late 2023 highlighted how investors can achieve more attractive total return in high quality, medium-term bonds – through the combination of yield and price appreciation – without taking on greater interest rate risk in long-dated bonds.

Economic outlook: Resilience in 2023 giving way to stagnation in 2024

Economic activity held up better than expected in 2023 despite aggressive central bank tightening, banking sector turmoil, and geopolitical stress.

Several factors contributed: Restrictive monetary policy raised borrowing costs but didn’t kick off a tightening in broader financial conditions. Swift government intervention helped contain the stress stemming from regional bank failures. Corporate margins were generally healthy, consumption was resilient, an easing in global supply chain bottlenecks helped cool inflation, and labor supply recovered.

This year, however, U.S. growth is likely to move more in line with the rest of DM into stagnation or mild contraction. Real savings buffers should soon return to pre-pandemic levels, as inflation has eroded the nominal value of households’ total wealth. Fiscal policy will likely be contractionary across DM, with the economic drag from higher borrowing costs continuing to build.

Additional improvements in labor force participation rates also look more difficult to achieve. Implementation lags mean the productivity benefits from new technologies, such as generative artificial intelligence, are likely only to accrue over a longer time horizon.

Economies with more interest-rate-sensitive, variable-rate debt markets are likely to slow at a faster rate (e.g., Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and Sweden), led by weaker consumption growth. The U.K. and Europe are also more interest-rate-sensitive than the U.S. and, in addition, look vulnerable due to Europe’s trade links to China, where growth also remains weak; the lingering effects of the energy shock from Russia’s invasion of Ukraine on terms of trade and investment; and the outlook for somewhat greater fiscal tightening.

Monetary policy outlook: Expect a lag before easing begins

DM central banks have likely now reached the end of their respective hiking cycles. Investors’ attention has turned to easing, including when and how many rate cuts could eventually come.

Historically, central banks haven’t cut rates ahead of recessions. Instead, cuts tend to coincide with rising unemployment and a falling output gap, when an economy is already in recession. Even in a handful of cases when a central bank did cut in the absence of recession, inflation had clearly peaked, while the unemployment rate rose back toward its longer-term average from a notably low level.

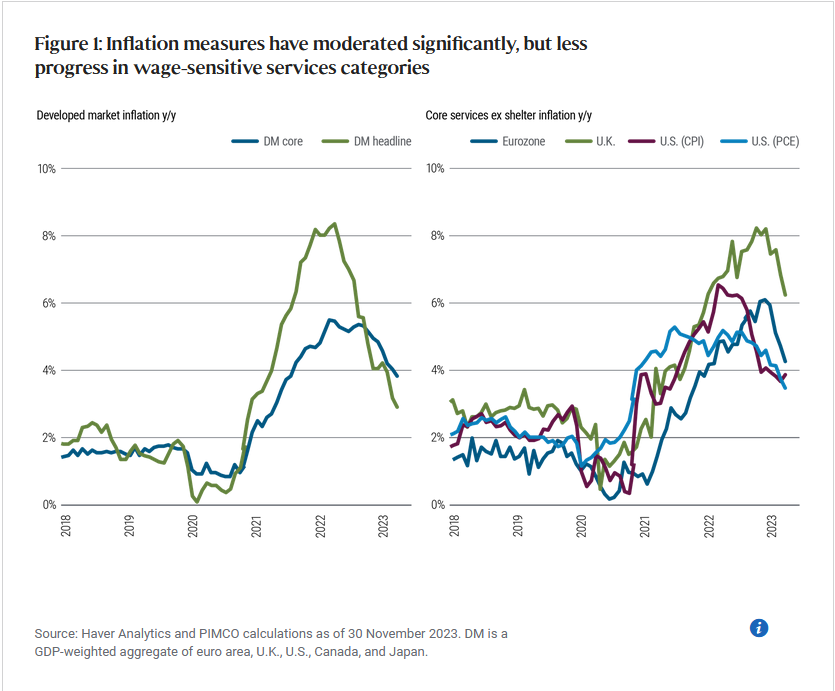

Today, measures of headline and core inflation have clearly peaked (see Figure 1), while unemployment rates have started to edge higher as labor market imbalances have generally eased. Nevertheless, labor markets remain tight, with less progress made in moderating inflation in wage-sensitive core services.

A DM immigration boom, spurred by post-pandemic border reopenings and geopolitical conflicts, has also complicated the task of monetary policy, since job-skills mismatch and supply-constrained housing markets may be limiting the disinflationary effects from higher potential labor supply. A fear of inflation reaccelerating, similar to the 1970s period under then-Fed Chair Arthur Burns, could also keep central banks waiting longer to ease than in the past.

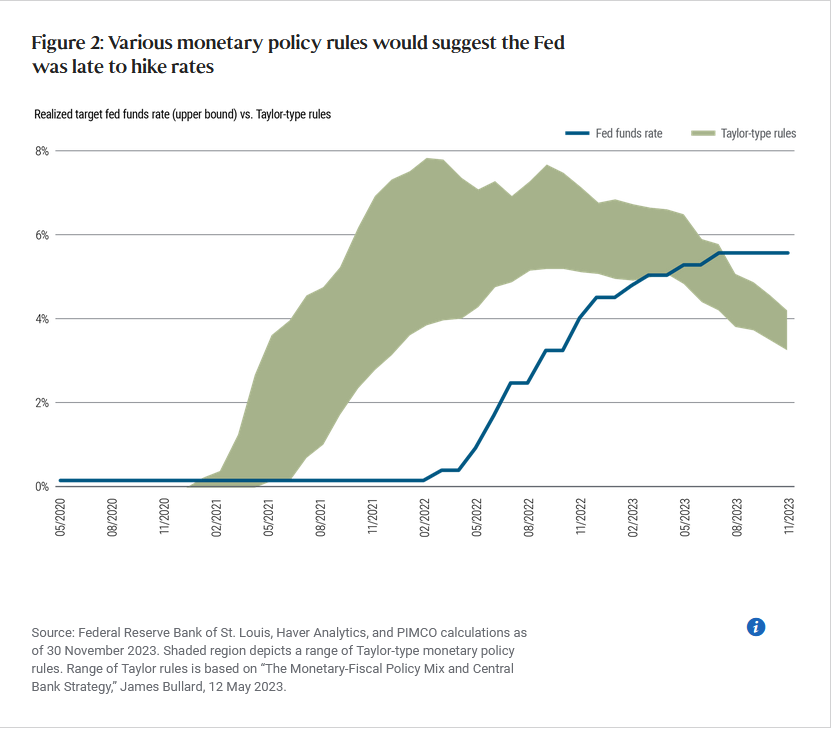

Estimating just how much central banks will lag is more art than science, even using established economic tools. For example, the Taylor rule – named after economist John Taylor – and related offshoots are widely used to gauge the relationship between policy rates, inflation, and growth.

Simple Taylor-type rules implied the Fed was nine months late to start raising rates in 2022. Using those same rules today would imply the Fed is already late to cut (see Figure 2). Yet these rules aren’t well-suited to prescribing policy in the face of supply shocks, and it’s uncertain where inflation will gravitate once pandemic-related effects more fully fade.

Overall, we expect DM central banks to start rate cuts closer to the middle of 2024 (potentially a bit earlier for the Fed), with the exclusion of the Bank of Japan, which we think will continue with its plans for modest rate hikes this year.

The implication of lagged monetary easing is that when central banks do start cutting, cuts can be more aggressive than markets anticipate. To be sure, this partly reflects the difficulty forecasters have in anticipating recessions – and the tendency of central banks not to cut until they are pretty confident the economy has entered recession with unemployment rising.

Based on a sample of 140 rate-hiking cycles across 14 developed markets from the 1960s to today, central banks have tended to cut their respective policy rate by 500 basis points (bps), on average, when their economies are entering recession. During cutting cycles that didn’t coincide with recession, the central banks still cut by 200 bps on average in the first year of easing. This is twice the every-other-meeting pace of 25-bp cuts embedded in the Federal Open Market Committee’s (FOMC) latest Summary of Economic Projections.

Overall, the magnitude of the hiking cycle that came directly before has been a good indicator of the magnitude of an easing cycle. Additionally, we continue to anticipate a return to an environment similar to The New Neutral period before the COVID-19 shock, with neutral policy rates expected to be similar to, or slightly above, levels before the pandemic, which would be consistent with more extensive rate cuts. (For more, see our latest Secular Outlook, “The Aftershock Economy.”)

A path toward a soft landing is not the only possible path

One of our main arguments for elevated recession risks is that the tighter-for-longer strategy that central banks have been communicating has historically not often coincided with economic soft landings. In instances when hiking cycles did not precede recessions – in the mid-1960s, mid-1980s, and 1990s – the central bank usually moved relatively quickly to cut rates, as a coinciding positive supply shock (global trade expansions, productivity booms, and OPEC production accelerations) contributed to falling inflation.

Post-pandemic supply chain normalization has already eased inflation measures off their peak in 2022. We expect this disinflation to continue in 2024, with headline and core measures dipping into the 2%–3% range year-over-year across DM. This, plus the potential for a faster cutting cycle, should raise the prospects for a soft landing.

However, with less room for further supply-side gains from a post-pandemic normalization, at the same time that demand is waning, we would hesitate to declare victory over either inflation or recession risks. With both supply and demand growth expected to be stagnant across DM in 2024, we think recession risks remain more pronounced than usual.

Inflation risks still look most pronounced in the U.S., where growth could remain somewhat more resilient relative to other DM economies. That’s due to the relatively slow pass-through of higher market rates into outstanding debt service payments; higher real excess savings due to larger pandemic-related fiscal stimulus; and growing support from previously enacted legislation aimed at supporting infrastructure, renewable energy, and supply chain investments, which could boost demand in the near term before supply-side benefits offset inflationary pressures.

Investment implications: Position for a broad range of opportunities

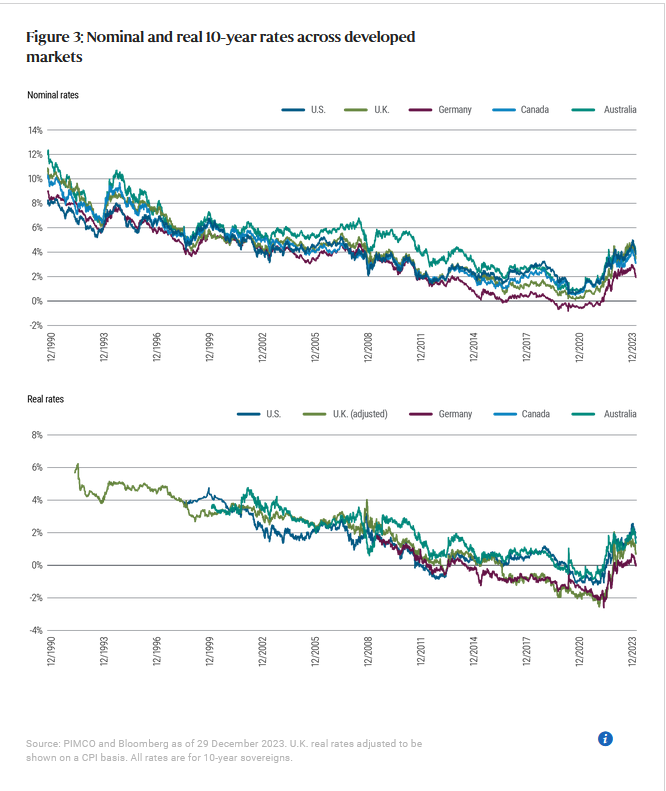

We view fixed income investments as broadly appealing over our cyclical horizon, given attractive yields and valuations as well as the potential for resilience across multiple economic scenarios. Such resilience is especially important in the wake of the increase in geopolitical risk and market volatility over the past two years. Because attractive yields can be found in high quality bonds, investors do not need to step down in credit quality.

Starting yields, which historically are highly correlated with returns, are still near the highest levels in 15 years, offering both attractive income and potential downside cushion. Inflation-adjusted yields also remain elevated as inflation continues to abate (see Figure 3). We continue to see Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities (TIPS) as a reasonably priced source of inflation protection, should upside inflation risks materialize.

Cash yields remain high but can only be locked in overnight, and they could decline quickly, especially if central banks start cutting policy rates. Investors risk missing out by holding cash too long while trying to time a re-entry into markets.

Because yield curves are unusually flat today, investors don’t need to greatly extend duration – a gauge of sensitivity to changes in interest rates, which is most pronounced in long-dated bonds – to unlock potential value. Intermediate bond maturities can help investors pursue attractive yield along with potential price appreciation should bonds rally, as occurred in late 2023 and as often happens in an economic slowdown.

More symmetrical risks

In our October Cyclical Outlook, “Post Peak,” we argued that global fixed income yields looked both attractive and high relative to the levels we expected to prevail over the cyclical horizon and beyond. After the U.S. had led a third-quarter rise in global yields, we said we expected to maintain overweight duration positions and to increase those with any further rise in yields.

At this point, we don’t see duration extension as a compelling tactical trade. We expect to be broadly neutral on duration after the most recent bond-market rally, which has brought global yields back in line with our expected ranges, and amid the shifting balance of inflation and growth risks. We see those risks as more symmetrical today.

We believe the Fed and other central banks have scope to cut rates aggressively if growth slows. Yet there are also scenarios in which the recent market-based easing of financial conditions has done much of the work for central banks. That easing, alongside continued consumer and corporate-sector strength, could even prompt inflation to flare up again.

This loop between central bank communication, financial conditions, and real economic performance will likely continue. We use scenario planning as part of our risk management process to position for a broad set of macro and market outcomes.

Opportunities across outcomes

We expect fiscal concerns will continue, both in the U.S. and globally. We see potential for further bouts of long-end curve weakness amid anxiety about elevated supply, as occurred in late summer, stemming from the increased bond issuance needed to fund large fiscal deficits. We therefore expect to have a curve-steepening bias in our portfolios, with overweight positions in the 5- to 10-year part of the curve globally, and underweights in the 30-year area.

At current valuations, we continue to find bonds attractive relative to equities (for more, see our latest Asset Allocation Outlook, “Prime Time for Bonds”), while fixed income can continue to offer correlation and diversification benefits in portfolios. Bond returns also tend to be less dependent on a positive economic outcome.

For example, if current economic conditions persist, bonds have the potential to earn equity-like returns based on today’s starting yield levels. If the economy enters recession, bonds will likely outperform stocks. If inflation revives and central banks need to hike again, both bonds and stocks would likely be challenged, but high starting yields can provide a potential cushion for bonds.

Maintaining a focus on liquidity and portfolio flexibility can allow us to respond to events as the balance between growth and inflation risks evolves. Active management allows us to more nimbly seize upon relative value opportunities as they arise.

Global markets may outperform

After central banks globally raised rates in relative synchrony, their paths ahead are likely to be more differentiated. We continue to see the potential for outperformance of global duration versus the U.S. Our view is based on the relatively higher chance of U.S. economic resilience and the greater downside risks in more rate-sensitive markets, notably, Australia, the U.K., and the eurozone.

We believe opportunities in global bond markets are more attractive than they have been over the past decade. Investors with broad, global platforms can access a diversified set of bond exposures and a variety of sources of potential return.

We expect to focus on more liquid DM overall, given attractive yield levels. We also expect to find good opportunities in emerging markets (EM), both in terms of local and external debt. We expect to be overweight EM foreign exchange, with diversified funding currencies to reduce the correlation between higher-carry EM currencies and global risk assets.

Focus on credit quality

In more credit-oriented markets, we continue to favor U.S. agency mortgage-backed securities as a high quality, liquid form of credit spread in portfolios. We also favor high quality non-agency mortgages, commercial mortgage-backed securities, and asset-backed securities, based on both current valuations and the default-remote properties of these securities given the collateral backing them.

In corporate credit, we favor liquid credit indices, senior financial sector debt, and high quality positions in investment grade and high yield bonds, while exercising greater caution with lower-quality credit and more economically sensitive sectors such as floating-rate bank loans.

The attractive opportunities we see in public markets today contrast with a more nuanced outlook for private credit amid the need to refinance loans in a tougher borrowing environment. Banks are retrenching in the face of liquidity constraints, regulatory restrictions, and cost-structure challenges, as we outlined in our recent publication, “Opportunities in Private Credit: Stepping In as Banks Step Out.”

In areas such as private credit, commercial real estate, and bank loans, we believe there is an important distinction between the stock of existing assets and the flow of new investment opportunities. The existing stock faces real challenges from higher interest rates and a slowing economy, with a substantial distance remaining to mark private assets to more realistic, market-based price levels, especially in areas with fundamental weakness.

At the same time, the opportunity for flexible capital has become more attractive, as borrowers are in need of creative solutions given a more constrained lending community. Asset-based lending is perhaps the best example of this, where we are seeing bank retrenchment create large-scale liquidity gaps in a variety of forms of consumer and non-consumer lending. This is particularly true in the U.S., as banks seek to sell assets, offload future lending obligations, or exit certain business lines entirely.

Over time, this painful period of adjustment may lead to further opportunities for well-positioned lending platforms to earn proper premiums for less-liquid investments. In turn, we anticipate what could be some of the best lending vintages across private markets since the global financial crisis. Even amid robust activity in corporate direct lending, which has recovered from most of the spread widening that happened since mid-2022, there is still significant need for flexible solutions to complex capital structure problems, many of which could offer equity-like returns in the near- to intermediate-term, in our view.

Download PIMCO's Cyclical Outlook

Download PDF

Related: Managing Return Expectations for 2024, Under Any “Landing” Scenario