Written by: Bryce Coward | Knowledge Leaders Capital

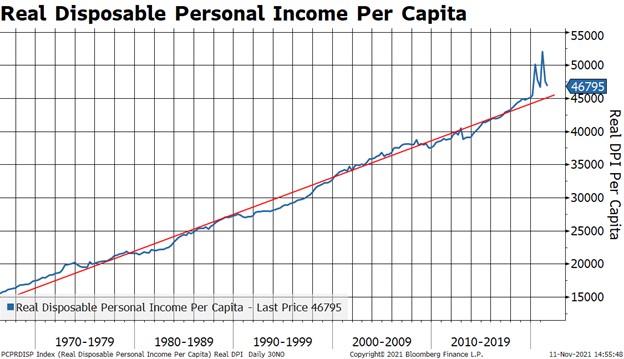

It’s no secret that pandemic-related government policy is driving at least some of the inflation currently being experienced in the United States. Indeed, real disposable income per capita has deviated from a linear trend in a meaningful way since 2020. The recent “breakout” in real disposable income was on top of the (much smaller) juicing provided by the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act in 2018, so it’s fair to say households have been feeling flush for some time now. As we will get to shortly, flush households mean more consumer spending. More consumer spending drives prices higher, especially when supply is limited.

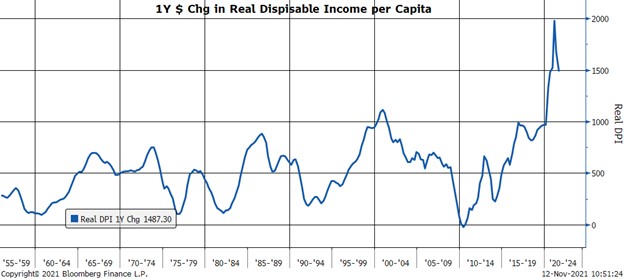

In this next chart we show the 1-year change in real disposable income per capita. In early 2020, it exceeded the highest level in the history of the dataset, and it continued making new highs through the early part of this year. If we just count the extra disposable income on a per capita since the pandemic started – that is, the cumulative amount of disposable income that exceeded the pre-covid trend – it amounts to about $10,500 per person. Multiply this by the population of the country (about 330m), and we get to a figure of $3.5tn. It is thus no wonder inflation has accelerated to 30-year highs, especially when we consider shortages in the supply chain.

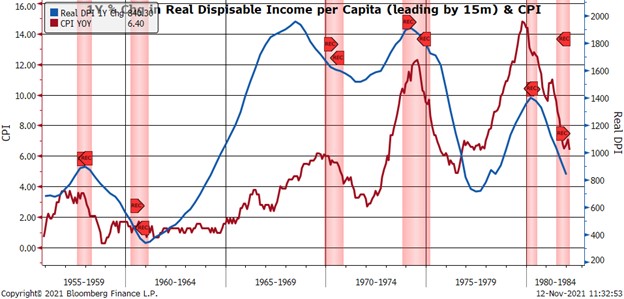

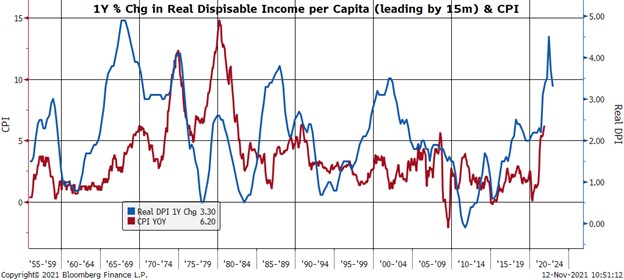

But, much of the inflation has already happened. The question now is when will it peak out? If we compare the 1-year percent change in real disposable income to CPI, we find that CPI lags changes in disposable Income by about 15 months, or 5 quarters. The good news (for inflation) is that disposable income stopped accelerating in March of 2021. The bad news is that this implies inflation will remain stubbornly hot through the first half of next year.

Of course, leads and lags between economic variables are unstable, so it’s quite possible that inflation could peak out before the second quarter of next year. The supply shock that is underway adds complexity and supports the “inflation for longer” story. Nevertheless, the 15 month lag between changes in disposable income and inflation may prove accurate. If we examine the last time the country dealt with an inflation spiral due in part to supply shortages (the 1965-1982 period) we do observe a fairly consistent lag of 15 months. The only problem was that each cyclical peak in inflation also coincided with a recession.