This is an exciting time for gold.

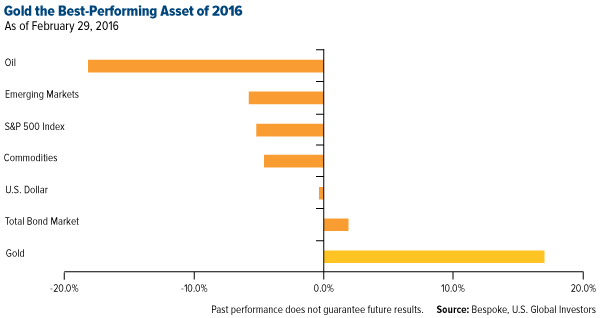

After another annual loss in 2015, its fourth year in a row, the precious metal has plotted a new course, one that has ferried it to the lead position among all other major asset classes in 2016.

I already shared with you that on Friday, gold signaled a “golden cross,” a bullish indicator that occurs when the 50-day moving average crosses above the 200-day moving average. As of February 29, just a day after gold Oscar statuettes were handed out in Hollywood, gold bullion has gained close to a phenomenal 17 percent year-to-date.

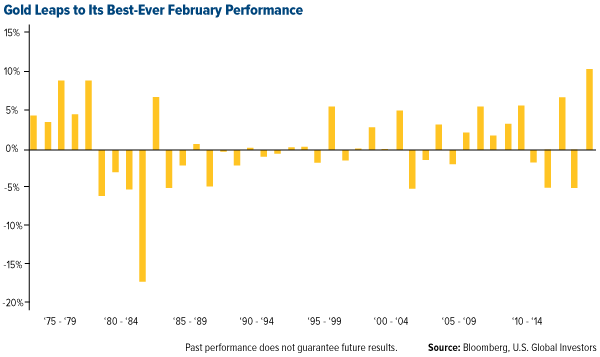

What’s more, this past month was its most impressive February performance since futures trading data began in 1975.

Many analysts now believe we’ve seen the final days of the gold bear market, which began after the metal touched its all-time high of $1,900 per ounce in 2011, with one analyst saying that “buying gold today may be comparable to buying stocks in April 2009.” (Between then and November 2015, the S&P 500 Index rose 145 percent.)

The metal’s surge is largely reflective of investors’ lack of faith in G20 central bankers and finance ministers’ ability to jumpstart global growth. The meeting held this past weekend in Shanghai was considered a major disappointment, with no clear resolution reached on how to address slow growth. But this is to be expected. As I’ve said before, G20 bankers seem more interested today in synchronizing global taxation and regulation than in balancing monetary and fiscal policies.

Ironically, though, one of the latest monetary tools—negative interest rates—has been a boon to gold prices. As rates have dropped below zero in Japan, Sweden, Switzerland and elsewhere, and with speculation they could be introduced here in the U.S., many investors have moved into, or increased their exposure to, gold. The metal has historically served as a dependable store of value.

Another driver of prices is the weak economic data that was released this Tuesday. China’s purchasing manager’s index (PMI) contracted even further in February, falling from 49.4 to 49.0. Meanwhile, the global PMI had a dramatic pullback, dropping to a neutral 50.0, which is its lowest possible reading before manufacturing begins to stagnate. We haven’t seen this level since 2012.