Written by: Richard Brink and Inigo Fraser Jenkins

For decades, globalization has been on an inexorable rise, a key pillar fueling economic growth, driving inflation and yields down, bolstering corporate profit margins and supporting an upward climb in market valuations. Over the past few years, though, cracks have started to develop in globalization, as populism has seen a resurgence and trade wars have erupted.

As part of AB’s Disruptor Series, we’ll explore changes in this and other secular trends that have supported returns for decades—and its implications for portfolio construction.

The COVID-19 pandemic and war in Ukraine have shown global supply chains to be fragile—with firms scrambling to address gaps. And because the gains from soaring markets have fallen more to capital than labor, unsettling income inequality has stoked a reaction against globalization. Collectively, these developments have led some to ask if globalization has peaked—and might give way to deglobalization, with big implications for economic growth, inflation and markets.

The Rise and Decline of the Fundamental Super-Cocktail

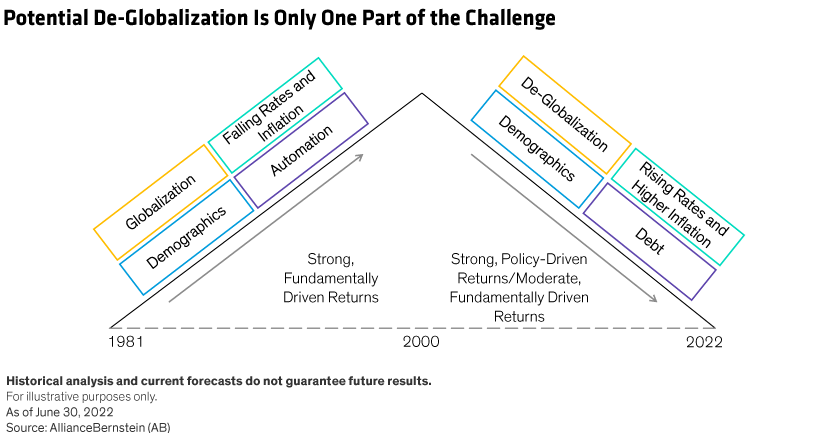

The bonanza for capital markets since 1980 hasn’t been all about globalization. That’s just one ingredient in a fundamental super-cocktail that also included powerful forces such as automation and technology, as well as what was then the largest labor force in human history. Meanwhile, falling—and low—inflation became a huge catalyst for valuation multiples and markets.

The results were spectacular. Since 1980, the S&P 500 has delivered an annualized return of 12.2%, well above the 7.9% for the three decades or so pre-1980. Since 1980, the traditional 60/40 portfolio of stocks and bonds returned a whopping 10.5% annualized.

The super-cocktail actually began to fade around 2000, as the Baby Boomer generation began to exit its peak earnings years. Interest rates had largely reached their natural bottoms, too, and productivity gains started to slow in developed economies—moderating the growth in gross domestic product (GDP). As relative household wealth continued to soar, heady markets endured a series of crises—the tech bubble, global financial crisis and the COVID-19 pandemic—and subsequent recoveries supported by extraordinarily accommodative fiscal and monetary policy.

The (Harder) Road Ahead for Investors

With the super-cocktail weakening, we think investors face a very different landscape as we move forward (Display). Economic growth rates are moderating and will likely be lower in the years ahead, amplified by increasingly unfavorable demographics. Inflation, though not likely to stay at its current highs, will probably be structurally higher from here.

With lower growth and labor flexing its strengthening muscles, corporate profit margins will be under more pressure, so market returns are highly unlikely to rival those of decades past. Lower nominal returns eroded by higher inflation will squeeze investors at both ends, translating into substantially lower real returns. Even if inflation declines to a 2.5% rate over the longer run, it will likely leave US Treasury returns with negative real yields. Even with yields having recently surged, the current environment poses significant challenges to the venerable 60/40.

Seeking Real Returns—and a Favorable Return Sequence

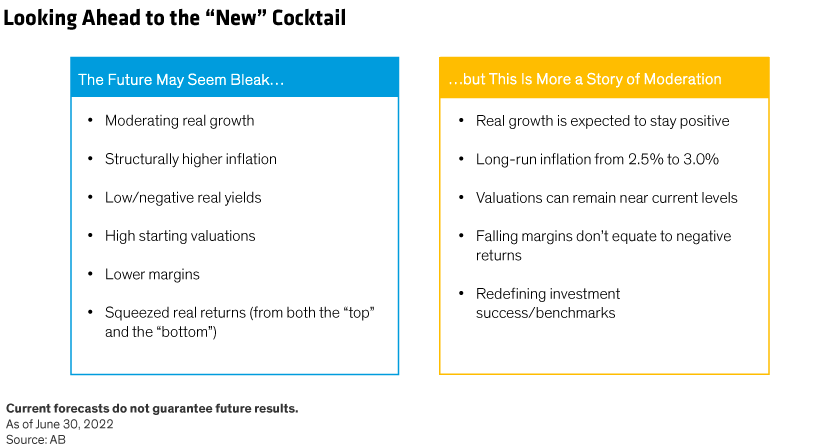

The new cocktail investors face in the years ahead sounds bleak, but a bit of perspective is important. The forward picture isn’t so much the story of falling off a cliff—it’s really a moderation from what had been a historically generous period for capital markets (Display).

In our view, the name of the game in the years ahead will be the ability to generate higher levels of real returns—and be flexible enough to tap into diverse return sources wherever they are. The key to long-term retirement wealth building is designing portfolios that produce a more favorable return sequence.

For the classic 60/40 model that has served investors for so many decades, at a high level, this will likely mean higher exposure to equities, given their ability to produce positive real returns when inflation is higher but not unanchored. Bear in mind that the link between inflation and equity valuations isn’t linear: very high inflation and deflation are typically damaging, but inflation in a range of 2.5%–3% is still consistent with positive real equity returns.

Allocations to traditional high-grade bonds might be pared back, given potential negative real returns and a modestly higher correlation with stocks—though certainly still diversifying. Within that bond allocation, it makes sense to pursue opportunities across a broader universe and assemble them in effective combinations. High-yield bonds can also be an effective portfolio-construction tool for de-risking part of that higher equity allocation.

Beyond that, it’s imperative for investors to consider other ways to find and integrate real return streams and premiums. Real assets come immediately to mind. Many investors have been substantially underinvested in real assets, given the secular low-inflation environment that prevailed. In a world of moderately higher inflation, real assets become vital, though investors need to be selective—not all real assets are created equal.

Certain factor exposures may be worth considering, too. Value has faced headwinds but has historically demonstrated a fairly close relationship with inflation, leaving a role for value in a sustained higher-inflation world. And if real yields remain low over the long run, some segments of growth stocks could be valuable—notably those that can deliver persistent growth.

Assembling these exposures efficiently is vital—as is finding ways to add alpha through active management. Even 20 or 30 basis points of alpha annually can be a big benefit in ultimate wealth accumulation. The good news from the fading of the super-cocktail and globalization? The related disruptions will likely create more variation in return patterns among regions, asset classes and sectors, offering skilled investors new avenues for adding alpha and diversification.

Benchmarks are another critical component of portfolio construction—how do we measure success? Rather than measuring a portfolio’s ability to beat the traditional 60/40 benchmark, perhaps it’s time to shift the lens, focusing instead on outcome-based measures, such as improving the measured probabilities of retirement success.

The bottom line is that investors must use every item in their toolkits to produce positive real returns over time, with some level of downside protection or volatility reduction.