Fixed-income isn’t what it used to be.

As the Wall Street Journal reports, the total amount of global government bonds that bear negative yields—meaning it costs you to have the government hold your money—has now climbed to a massive $13 trillion.

This figure is likely to grow as yields continue to plumb the depths of negative territory, giving global investors little choice but to seek income elsewhere.

For some, it’s corporate debt. But even these securities have fallen significantly since the start of the year, many below zero. Bloomberg reports that roughly $512 billion worth of European, investment-grade corporate bonds now offer a negative yield.

It’s not much better in the U.S. Blue chip Walt Disney just issued a 10-year bond with the low, low yield of 1.85 percent.

For other investors, it’s American municipal bonds, which still offer attractive, tax-free income, not to mention low volatility and low default rates. Back in May, I shared with you how yield-starved foreign investors were piling into munis at an impressive clip, even though they’re ineligible to take advantage of the tax benefit. But no matter—at least it’s not costing them to participate, unlike a growing percentage of negative-yielding government debt.

##TRENDING##

Negative bond yields have also boosted demand for gold, which has had two of the most spectacular quarters in modern history. Although it doesn’t provide any income, the yellow metal has been treasured as an exceptional store of value, especially in times of political and macroeconomic uncertainty. Gold stocks are up more than 115 percent year-to-date, as measured by the NYSE Arca Gold Miners Index and Swiss financial services firm UBS puts gold prices near $1,400 by year’s end.

(Gold prices are also being supported right now by the likelihood that we’ve reached “peak gold.” According to my friend Pierre Lassonde, cofounder of Franco-Nevada, new discoveries have fallen steadily since the 1980s, while current mine production has not kept up with demand.)

Are Stocks the New Bonds?

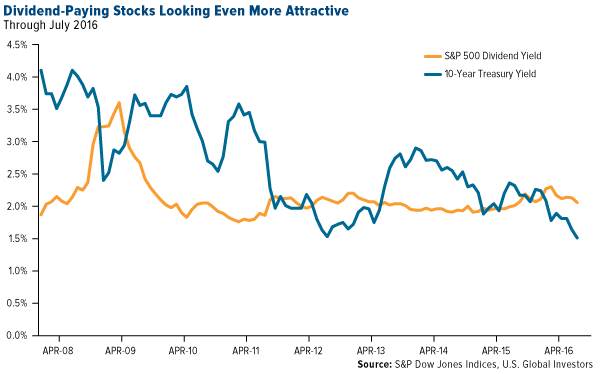

The hunt for yield has also inevitably landed many income investors in dividend-paying stocks. According to Reuters, about 60 percent of S&P 500 Index stocks now offer dividend yields that exceed the 10-year Treasury yield, which hit an all-time low of 1.36 percent earlier this month.

This is one of the main reasons why recent cash flows into U.S.-based stock funds have been so strong. Money goes where it’s most respected. In the week ended July 13, ETF and mutual fund equity funds took in a whopping $33.5 billion in net new money, the largest positive weekly net inflow of the year.

Meanwhile, Treasury bond funds have been witness to some huge outflows this year. For the week ended July 25, the iShares 7-10 Year Treasury Bond ETF lost $90.5 million. Back in April, foreign investors unloaded nearly $75 billion in U.S. Treasuries, the single largest monthly amount since transactional recordkeeping began in 1978.

Increasing Dividends over the Past Three Years

In selecting the best dividend-paying stocks, we like to identify those that have grown their payments the most over the past three years. Using that metric, the leader by far right now is Alabama-based Vulcan Materials, which has increased its dividend a jaw-dropping 1,900 percent, according to FactSet data. Many financial groups, including Regions Financial and Zions Bancorporation, have also been very generous in rewarding shareholders.

The challenge going forward has to do with corporate earnings. Dividend growth is largely driven by earnings, which are expected to be down 3.7 percent in the second quarter once all companies have reported. This will mark the sixth consecutive quarter of declines.

Energy stocks lead the way down, with crude oil prices at nearly three-month lows after falling over 20 percent since early June.

Apple is perhaps the largest contributor to declines this quarter. The iPhone-maker posted net income of $7.8 billion, a massive 27 percent drop from the $10.7 billion it recorded during the same period last year.

But let’s give the tech giant a break—it just sold its one billionth iPhone last week, despite a decrease in sales for the second straight quarter. I must also add here that Apple is the undisputed dividend king, having paid out $2.9 billion in the first quarter alone.

Standouts this earnings season included Facebook, Amazon and Alphabet (Google)—three-quarters of the FANG tech stocks—all of which crushed expectations. Mark Zuckerberg’s social media giant handily beat analysts’ estimates on the top and bottom lines as well as ad revenue, which totaled $6.2 billion during the quarter. This helped add $5 billion to Facebook’s market capitalization, pushing it ahead of Warren Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway.

Buffett was also surpassed last week by Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos, whose wealth leaped $2.6 billion after an extraordinary earnings report. He’s now the world’s third-richest man, ahead of the Oracle of Omaha.

Netflix, on the other hand, reported a disappointing 59 percent loss in profits, from $40.5 million in the first quarter to $16.7 million. The popular streaming service added only 1.7 million subscribers during the quarter, far below its guidance of 2.5 million.

##PAGE_BREAK##

Banks on the Chopping Block?

Well, there’s no questioning it now: Donald Trump and Hillary Clinton have both been anointed as our presidential candidates. Many wondered if Bernie Sanders would try to disrupt the nomination process and insist on a brokered convention, similar to what Franklin Roosevelt did in 1932. Sanders’ supporters certainly put up a fight, but in the end, Clinton prevailed.

This week before last, I suggested that the only thing Trump and Clinton have in common with each other is they’re both in favor of increasing infrastructure spending. It’s now come to my attention that no matter who wins, there could be an effort to break up the big banks, as both parties’ platforms include an interest in reviving the Glass-Steagall Act of 1933. The goal, of course, would be to prevent another financial crisis, but whether the banking act would actually work is up for debate.

Another solution might be to break up the regulatory bodies into two separate branches—one overseeing banks, the other overseeing all other financial and investment institutions, from brokers to insurance companies to mutual fund companies. Each side would have its own unique set of rules and regulations. What’s good for banks isn’t necessarily good for investment firms, and vice versa, because they’re often playing very different games.

Think of it this way: We expect referees to be experts in their particular sport. That only makes sense. But imagine if all competitive sports, from basketball to hockey to softball, suddenly drew from the same pool of referees. Games would be conducted a lot less efficiently. Officials would constantly be putting on and taking off different hats. One game’s set of rules might mistakenly (and awkwardly) be applied to a completely different game.

This is what’s happening in the financials industry as a whole.

As I always say, regulations are often well-intentioned. There’s a reason why they exist. We need them to maintain a level and fair playing field.

At the same time, it’s important that they be common sense and not hinder or prohibit everyday, lawful business activity.