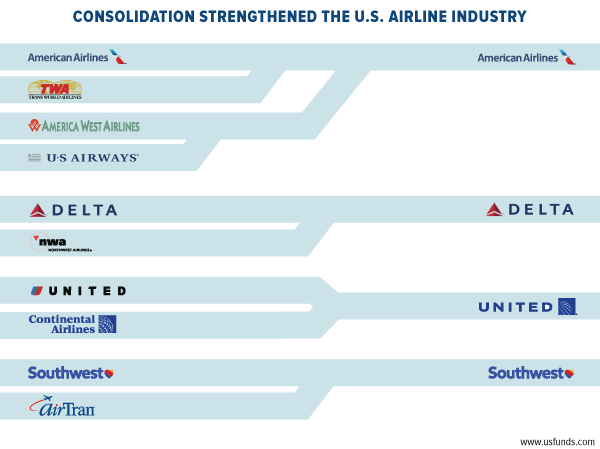

A little over 10 years ago, there were a dozen major domestic airlines. Following a wave of bankruptcies, the industry consolidated, and today four remain—American, Delta, United and Southwest.

For the past couple of years, these newly-strengthened carriers, along with a full roster of regional and low-cost carriers, have been beating expectations, generating record profits and free cash flow and rewarding shareholders with dividend growth and stock buybacks. Low fuel costs have served as an additional windfall.

That doesn’t mean the industry now lacks the room to change (and improve), however. In February, the short-haul regional carrier Republic Airlines filed for bankruptcy—the first such filing in the industry since American’s in 2011—after losing a number of unionized pilots in a drawn-out salary dispute. (More on that later.)

And just this past weekend, 84-year-old Alaska Airlines announced it would be buying Virgin America, billionaire Richard Branson’s young, hip carrier.

Alaska to Become the Premiere West Coast Carrier?

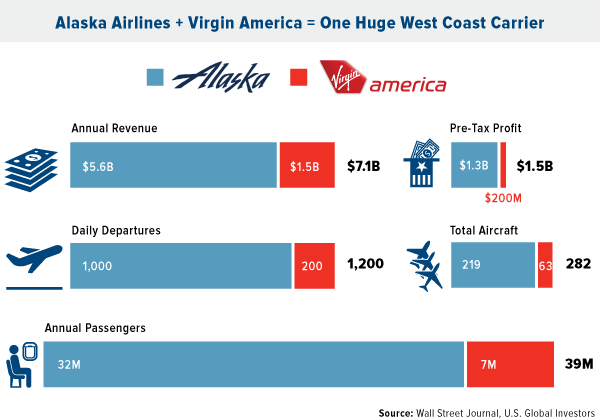

The $2.6 billion deal, awaiting shareholder approval in June, would create the fifth-largest U.S. airline by traffic and result in a much more competitive player, especially on the West Coast. (Alaska is based in Seattle, Virgin in San Francisco.) According to the Wall Street Journal, Alaska’s annual revenue could grow 27 percent because of the deal.

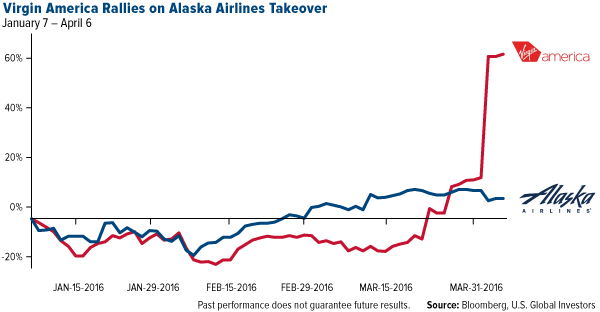

As I’ve pointed out in the past, the acquiree in deals such as this normally sees a short-term bump in share price, while the buyer’s stock might fall because, among other reasons, it must pay a premium for the acquisition. For the three-month period as of April 6, Virgin was up nearly 66 percent.

Integration can sometimes be tricky for airlines—more so than for other industries—because they involve not just employees and aircrafts but also information technology systems, booking procedures, rewards programs and flight schedules. All of this must be accomplished while the carriers remain fully operational.

Airlines that have gone through this often-messy process have seen their quality ratings drop off. This was certainly the case with American as it slowly integrated and digested US Airways, a two-year endeavor that concluded in October 2015.

The Alaska-Virgin deal could end up being very different, though. Both carriers have an exceptionally firm handle on their operations and provide sterling customer service. Alaska has received the highest rating in J.D. Powers’ North America Satisfaction Survey for eight consecutive years. For the fourth straight year, Virgin has held the top spot in the annual Airline Quality Rating (AQR) system, developed to rank airlines based on 15 “elements” such as on-time arrivals, mishandled baggage and the like.

Aircraft integration between the two companies poses arguably the most significant challenge—not just for Alaska and Virgin but also for jet manufacturer Boeing. Alaska exclusively flies the Boeing 737 while Virgin operates the Airbus A320, almost all of them leased. Once the Airbus leases are up in 2020, Alaska could choose to let them go, or it might decide to keep or even expand the fleet. At some point, this could be a concern for Boeing.

Pilot Shortage Intensifies While Demand Soars

Nevertheless, Boeing has an unprecedented seven-year order backlog of 5,800 commercial jets. To put that number in perspective, the U.S. airline industry collectively has 6,871 jets in its commercial fleet right now, according to the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA). Because of increased passenger and cargo demand, this number is expected to reach at least 8,400 by 2036.

This raises the question of who will be flying these additional aircrafts.

I’ve previously written about the imminent pilot shortage , which was spurred on by new FAA rules that tightened pilot training and service. Pilots must now retire when they reach 65, and they must have at least 1,500 hours of flight time before they can be considered for a position—usually with a regional carrier such as Republic for a starting salary close to $20,000. While Republic was trying to negotiate a new labor contract, it was losing about 40 pilots a month, according to Bloomberg.

This has contributed to an industrywide pilot shortage that could intensify as more and more pilots retire, with fewer and fewer new pilots to replace them. It also has the effect of encouraging capacity growth discipline.

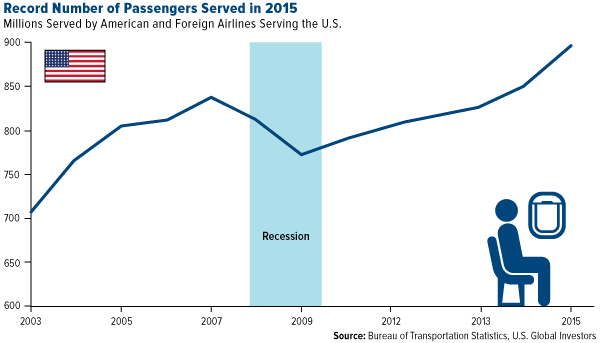

Meanwhile, commercial flight demand, both here and abroad, continues to climb. According to the Transportation Department, the number of passengers carried by U.S. airlines and foreign airlines serving the U.S. reached an all-time high of 895.5 million in 2015, a 5 percent increase from the previous year.

Passenger traffic in the world’s busiest airport , Hartsfield-Jackson in Atlanta, also grew 5.5 percent year-over-year in 2015 to reach a record-breaking 100 million passengers, according to Airports Council International (ACI).

By the way, I want to congratulate Brussels Airport for (partially) reopening following the devastating attacks last month. The repairs will no doubt take a long time and cost millions of dollars, but this is the first step among many toward normalcy.

The role airports play in the U.S. economy is hard to exaggerate. They contribute a jaw-dropping $768.4 billion per year to the national economy, or nearly 5 percent of GDP, according to the Transportation Research Board’s Airport Cooperative Research Program (ACRP). What’s more, they generate $1.6 trillion in goods and services and provide 7.6 million jobs—4.3 percent of all U.S. jobs—that pay workers a combined total of $453 billion.

Clearly we depend on airports, but how are they funded? In a word: munis.

American airports as a whole have capital needs that average $14.3 billion per year, according to ACI estimates. The FAA annually provides $3.35 billion, leaving a difference of $10.95 billion. About 54 percent of that amount is typically funded with general obligation (GO) bonds and other municipal bonds that are tax-free at the federal level and often at the state and local levels.