Over the last eight months, I have written a series of posts on the market and how it has adapted and adjusted to COVID. The very first of these posts, on February 26, 2020, was about two weeks into the meltdown and it is indicative of how little we knew about the virus then, and what effects it would have on the economy and the market. More than seven months later, there is still much that we still do not know about COVID, as it continues to wreak havoc on global economies and businesses. In this post, I intend to wrap up this series with a final post, reviewing how value has been reallocated across companies during the months, and providing an updated valuation of the S&P 500. Given that much of Europe is going into lockdown, and that there is no vaccine in sight, this may seem premature, but I have a feeling that there will be other uncertainties that will vie for market attention over the coming weeks, especially as the US election results play out in legal and legislative arenas.

A Market Overview

For those of you who have read my prior posts on COVID's market effects, I will follow a familiar script. I will start by noting that this crisis has played out in markets in three acts, captured in the graph below where I look at the S&P 500 and the NASDAQ, since the start of this year:

The year began auspiciously for US equities, as stocks built on positive performance in 2019 (when it was up more than 30%) and continued to rise. In fact, on February 14, US equities were are at all time highs, when news of the virus encroaching into Europe and then rapidly expanding across the world caused stocks to go into a tailspin that lasted just over five weeks. On March 23, 2020, amidst talk of doomsday for stocks, momentum shifted, with some credit to the Fed, and stocks went on a run that extended through the end of August, recovering almost all of the ground lost during the meltdown. In September and October, stocks were choppy with more bad days than good, as investors recalibrated. While the graph is US-centric, this was a global crisis, and equities around the global moved through the same three phases, as you can see in the table below, where I look at selected equity indices from around the world:

|

| Download data |

Note that the pattern is very similar, across indices, with steep drops in the first phase (2/14-3/20), followed by steep increases in the following months (3/20-9/1) before settling down in the last two months (9/1-11/1). As equities went on a turbulent ride, other asset classes were also affected, with US treasuries benefiting from a flight to safety in the first five weeks:

|

| Download data |

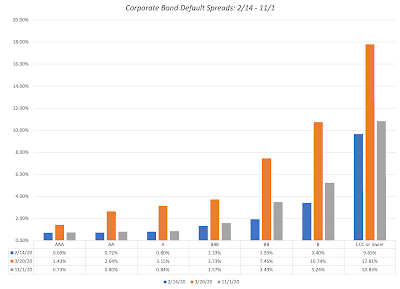

US treasury yields dropped across all maturity classes between February 14 and March 20, with short term rates dropping close to zero and 10-year T.Bond rates dropping fro 1.7% to 0.7%. I know it is fashionable now to attribute all things related to interest rates to the Fed's actions, but the bulk of the decline in treasury rates occurred before the Fed finally acted in mid-March, and it is surprising how little movement there has been in treasury rates in the months since. Though treasury yields have stayed at their mid-March levels, the rise and fall of the fear factor in the equity markets also played out in the corporate bonds, in the form of movements in corporate default spreads:

|

| Download data |

When stocks were melting down between February 14 and March 20, corporate bond spreads were also widening dramatically, but those spreads have fallen back almost to pre-crisis levels for the higher ratings, and mostly recovered even for the lower ratings.

Looking at oil and copper, two economically sensitive commodities, you see reflections of the turbulence that affected equities and corporate bond markets:

|

| Download data |

Both oil and copper prices dropped significantly between February 14 and March 20, with oil showing a much larger decline (down more than 50%) than copper (about 15%), but both commodities have recovered, with copper now up almost 17% from pre-crisis levels. Oil, in spite of its comeback in the last few months, is still down more than 30% from pre-crisis levels. Finally, I look at gold and bitcoin, an odd pair, but both touted by their advocates as crisis assets:

|

| Download data |

While bitcoin is now up more than gold over the period, gold has performed better as a crisis asset, holding its own when equities were melting down between February 14 and March 20. In contrast, the crypto currencies (Bitcoin and Ethereum) have behaved like very risky equities, going down more than equities, when stocks were going down, and rising more, when they rose.

Equity Markets: A Wealth Transfer

The quick recovery in equity markets has led some to believe that the market has ignored the crisis, but that is not true. While equity values have recovered globally, there has been a significant shift in value across regions, sectors and company types. While I have talked about this value reallocation in previous posts, I will update the numbers and provide a summary of what the data is showing as of November 1. First, this crisis has played out very differently in different parts of the world, as you can see below, where I break down the market capitalizations of all publicly traded companies, by region, on February 14, 2020 and on November 1, 2020, with a table showing the percentage changes over the period:

|

| Download data |

The markets that are showing the most residual damage are Africa, Eastern Europe & Russia and Latin America. While the easy explanation is that they are all emerging markets, note that Asia has emerged not just unscathed, but as one of the best performing regions of the world. Among the developed markets, the UK is the worst performer, perhaps dragged down by the continued uncertainty of how Brexit will play out. A better explanation would be that these are regions heavily dependent on natural resource and infrastructure businesses, and as we will see in the next section, those have been adversely affected by this crisis. In addition, since these returns are in US dollars, currency movements add to the effect, with depreciating (appreciating) currencies, against the dollar, worsening (improving) returns. Building on the theme that damage has varied across sections, I break down aggregate market cap by sectors, on February 14 and November 20, in the graph below (also with percent changes over the period:

|

| Download data |

Again, the shift in value is clear and decisive, with consumer discretionary, technology and health care gaining at the expense of energy, real estate, utilities and financials. Put simply, capital light businesses have gained at the expense of capital intensive ones, and breaking down sectors into finer industry detail, emphasizes this shift, with the ten best and worst performing industries below:

|

| Download data |

In an earlier post, I connected this value shift across industries to corporate life cycles, noting that younger, higher growth companies have gained value at the expense of older, more mature businesses, as can be seen in the tables below, where I break down the value change across companies, first by age, and then by expected revenue growth rate, into deciles:

|

| Download corporate age data & revenue growth data |

The youngest companies have gained value over this crisis, whereas the oldest companies have lost value, and high growth companies have benefited at the expense of low growth firms. As this shift has occurred, it is not surprising that the stocks most favored by value investors (low PE/PBV, high dividends) have underperformed the stocks that are most favored by growth investors. I capture this in the table below, where I first look at value changes across companies, first classified across PE ratios and then across dividend yields:

|

| Download PE decile data & Dividend decile data |

Value investors have also warned us over the last decade about two trends in corporate behavior, an increase in debt loads at some companies and a surge in stock buybacks. To evaluate whether those warnings were justified, I looked at companies classified by debt load (net debt to EBITDA) into deciles and computed value changes between February 14 and November 1.

|

| Download data |

On this front, I think that the message is clear that the more indebted a company, the more exposed it was to damage during this crisis. On the buyback front, the results are a little murkier. In the graph below, I look at value changes for four groups of companies, (1) those that returned no cash at all in 2019 (no dividends or buybacks), (2) those that paid only dividends, (3) those that returned cash in the form of buybacks and (4) those that did both:

There is a muddled message in this graph. While companies that returned no cash to their shareholders in 2019 fared better overall than companies that returned cash (either in dividends or in buybacks) in 2019, companies that returned cash only in the form of buybacks recovered faster and more completely the companies that paid only dividends. Companies that both paid dividends and bought back stock did worst of all. If flexibility is key to surviving a crisis, it is possible that this crisis will make companies more reluctant to return cash, in general, and when they do, it is also more likely that you will see that cash returned in the form of buybacks than dividends, since the former are easily retracted but the latter are sticky.

Finally, no post on US equities is complete without a mention of the FANGAM stocks, a topic that I focused on in my last post. Updating the numbers through November 1, here is how these six companies have performed over the crisis, relative to the rest of the market:

|

| Download data |

As you can see, the FANGAM stocks have added $1.25 trillion in aggregate market cap since February 14, while all other US equities have shed $1.32 trillion over that period. If the market has almost fully recovered from its early swoon, the credit has to go almost entirely to these six companies.

The Resilient Risk Capital Thesis

The best way to summarize how this crisis has affected companies is to summarize the value transfer from what would be consider "risk on" categories (young, high growth, high PE, low or no dividends and high debt) to "risk off" categories (old, low growth, low PE, high dividends and low debt), looking at the top and bottom deciles of each grouping:

Note that in almost every category, other than debt, the "risk on" group gained value at the expense of the "risk off" group. One explanation that I offered in my post from a few weeks ago was that, unlike prior crises, risk capital (defined as capital invested in the highest risk assets, such as venture capital and investments in below investment grade bonds) has stayed in the game, as can be seen in the behavior of VC fund flows and issuances of high yield bonds (updated to include the third quarter of 2020):

In fact, it is this resilience of risk capital that explains why the equity risk premium for the S&P 500, which soared in the first five weeks of this crisis, has reverted back to pre-crisis levels:

|

| Download data |

Put simply, markets, for better or worse, seem to be sending the message that the fear factor of the crisis has passed, though earnings and cash flows will need to be tweaked.

Market Assessment: Predictive Mechanism or Animal Spirits

As markets have risen over the last few months, there has been a fair amount of hand wringing about animal spirits and irrational exuberance driving markets higher. Some of this concern has come from the clear disconnect between stocks going up and economic malaise, but I noted that this is neither unusual nor unexpected, using this graph of stock returns and real GDP growth, by quarter:

|

| Download data |

Looking at the quarterly data over the last 60 years, there has been little to no relationship between stock returns in a quarter and the GDP change in that quarter, and if there is one, it is mildly negative, i.e., stocks are slightly more likely to go up (down) in a quarter when GDP is down (up). While that may surprise some people, it is entirely understandable, when you recognize that stock markets are predictive mechanisms, and that is borne out by the data, with stock returns becoming positively correlated with GDP growth in future quarters. Note that while the correlation increases as you look three or four quarters ahead, it flattens out at about 0.26 indicating that markets are noisy predictors; they are wrong as often as they are right, but given a choice between trusting markets and going with market gurus, I will take the former every single time.

There is a debate to be had about whether markets have over adjusted to the possibility of a vaccine and the economy reopening, and to address that question, I decided to value the S&P 500 again; I did value it on June 1, 2020 and found it to be close to fairly valued. I revisited my assumptions, updating my estimates of earnings for the index in the near years (2020, 2021 and 2022), where the bulk of the damage from this crisis will be done.

Note that in the intervening five months, since my last valuation, analysts tracking the index have become more optimistic about earnings in 2020 and 2021. The resulting valuation reflects these improved estimates:

|

| Download spreadsheet |

Based upon my inputs, I arrive at a value for the index of just over 3100, which would make stocks mildly over valued. I also followed up with a simulation of this valuation, based upon distributions for my key inputs, and the results are below:

|

| Download spreadsheet with simulation results |

The simulation reinforces the findings in the base case valuation. You could make a case that stocks are over valued, and that case will be built on the premise that the economic damage from this crisis will be much greater and long lasting that analysts believe. However, if your argument is that markets have gone crazy and that nothing explains stock prices, you may want to evaluate that view, and consider at least the possibility that your world view (about how the economy will recover and the virus will play out) is wildly at odds with the market consensus. That leaves open the unpleasant possibility that it is you that is being irrational and wrong, not the market.

Crisis as Crucible: Lessons learned, unlearned and relearned

Every crisis is a crucible, exposing what we don't know and putting our faith to the test. This one has been no different, and while I will not tell you that I have enjoyed it, I have learned some lessons from it.

- Respect markets, even if you disagree with them: Markets are not all knowing and they are definitely not efficient, but they are extraordinary platforms for conveying a consensus view of the future. While you and I may disagree with the market view, and markets can be wrong, it behooves us all to at least try and understand the message that it delivers.

- Time to move on: For many managers and investors, the COVID crisis is a reminder, sometimes in painful terms, that we are now well into the 21st century and continuing to use tools, techniques and metrics that were developed and tested on 20th century data is a recipe for disaster. That was the underlying message in my posts on value investing from last month.

- Importance of Flexibility: If you look across what companies that have done well during this crisis share in common, it is flexibility, with companies that can adapt quickly to new circumstances improving their odds of winning. In the same vein, it seems self defeating for companies to borrow too much or lock themselves into paying large dividends, since both reduce their capacity to respond quickly to changed circumstances.

All in all, it has been an interesting roller coaster ride over these last few months, and I am glad that you were able to join me for at least some of the ride. It is definitely not over, but I have a feeling it is time for me to move on. There are other attractions at this fair!