In the weeks since my first update on the crisis on February 26, 2020, the markets have been on a roller coaster ride, as equity markets around the world collectively lost $30 trillion in market cap between February 14, 2020 and March 20, 2020, and then clawed back more than half of the loss in the following month. Having lived through market crises in the past, I know that this one is not quite done, but I believe we now have lived through enough of it to be able to start separating winners from losers, and use this winnowing process to address three big questions that have dominated investing for the last decade:

- Has this crisis allowed active investors to shine, and use that performance to stop or even reverse the loss of market share to passive vehicles (ETFs and index funds) that has occurred over the last decade?

- Will this market correction lead to growth/momentum investing losing its mojo and allow value investors to reclaim what they believe is their rightful place on top of the investing food chain?

- Will the small cap premium, missing for so many decades, be rediscovered after this market shock?

I know each of these is a hot button issue, and I welcome disagreement, but I will try to set my biases aside and let the data speak for itself.

Market Action

As with my prior updates, I will begin by surveying the market action, first over the two weeks (4/17-5/1), following my last update, and then looking at the returns since February 14, the date that I started my crisis clock. First up, I look at returns on stock indices around the world, breaking them up into two periods, from February 14 to March 20, roughly the low point for markets during this crisis and from March 20 to May 1, as they mounted a comeback.

The divide in the two periods is clear. Consider the S&P 500, down 28.28% between 2/14 and 3/20, but up 22.82% from March 20 and May 1, resulting in an overall return of -11.92% over the period. While the magnitudes vary across the indices, the pattern repeats, with the Shanghai 50 close to breaking even over the entire period, and the Bovespa (Brazil) and the ASX 200 (Australia) delivering the worst cumulative returns between 2/14 and 5/1. As stock markets have swooned and partially recovered, the yields on US treasuries dropped sharply early in the crisis and have stayed low since.

The 3-month treasury bill rate, which was 1.58% on February 14, has dropped close to zero on May 1, and the treasury bond rate has declined from 1.59% to 0.64% over the same period. The much talked about inverted yield curve late last year, that led to so many prognostications of gloom and doom, has become upward sloping, and staying consistent with my argument that too much was being made of the former as a predictor of recession, I will not read too much into its slope now. Moving to the corporate bond market, I focused on 10-year corporates in different ratings classes:

Early in this crisis, the corporate bond markets did not reflect the worry and fear that equity investors were exhibiting, but they caught on with a vengeance a couple of weeks in, and the damage was clearly visible by April 3, 2020, with default spreads almost tripling across the board for all ratings classes. Since April 3, the spreads have declined, but remain well above pre-crisis levels. There should be no surprise that the price of risk in the bond market has risen, and as the crisis has taken hold, I have been updating equity risk premiums daily for the S&P 500 since February 14, 2020:

The equity risk premium surged early in the crisis, hitting a high of 7.75% on March 23, but that number has been dropping back over the last weeks, as the market recovers. By May 1, 2020, the premium was back down to 6.03%, with pre-crisis earnings and cash flows left intact, and building in a 30% drop in earnings and a 50% decline in buybacks yields an equity risk premium of 5.39%. For good reasons or bad, the price of risk in the equity market seems to be moving back to pre-crisis levels. I don’t track commodity prices on a regular basis, but I chose to track oil and copper prices since February 14:

At the risk of repeating what I have said in prior weeks, the drop in copper prices is consistent with an expectation of a global economic showdown but the drop in oil prices reflects something more. In fact, a comparison of Brent and West Texas crude oil prices highlights one of the more jaw-dropping occurrences during this crisis, when the price of the latter dropped below zero on April 19. The oil business deserves a deeper look and I plan to turn to that in the next few weeks. Finally, I look at gold and bitcoin prices during the crisis, with the intent of examining their performance as crisis assets:

Gold has held its own, but I think that the fact that it is up only 7.4% must be disappointing to true believers, and Bitcoin has behave more like equities than a crisis asset, and very risky equities at that, dropping more than 50% during the weeks when stocks were down, and rising in the next few weeks, as stocks rose, to end the period with a loss of 16.37% between February 14 and May 1.

Equities: A Breakdown

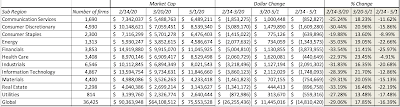

Starting with the market capitalizations of individual companies, I measured the change in market capitalization on a week to week basis, allowing me to slice and dice the data to chronicle where the damage has been greatest and where it has been the least. Breaking down companies by region, here is what the numbers updated through May 1 look like:

Latin America has been the worst performing region in the world, with Africa, Australia and Russia right behind and China and the Middle East have been the best performing regions between February 14 and May 1. I continue the breakdown on a sector-basis in the table below:

Health care, consumer staples and technology have been the best performing sectors and financials are now the biggest losers. Extending the analysis to industries and looking at the updated list of worst and best performing industries:

Repeating a refrain from my updates in earlier weeks, this has been, as crises go, about as orderly a retreat as any that I have seen. The selling has been more focused on sectors that have heavy capital investment and oil-focused, burdened with debt, and has been much more muted in sectors that have low capital intensity and less debt.

Value versus Growth Investing

In the tussle between value and growth investing, value investors have held the upper hand for a long time. In addition to laying claim to being the custodians of value, they also seemed to have all the numbers on their side of the argument, as they pointed to decades of outperformance by value stocks, at least in the United States. The last decades, though, have delivered numbers that are more favorable to growth investors, and this crisis is perhaps as good a time as any to reexamine the debate.

The Difference

For decades, we have accepted a lazy categorization of stocks on the value versus growth dimension. Stocks that trade at low PE or low price to book ratios are considered value stocks, and stocks that trade at high multiples of earnings and book value are growth stocks. In fact, the value factor in investing is built around price to book ratios. If you are a value investor, your reaction to this categorization is that this is no way to describe value and that true value investing incorporates many other dimensions including management quality, sustainable moats and low leverage. Conceding all those points, I would argue that the key difference between value and growth investing can be captured by looking at a financial balance sheet:

Thus, the real difference between value and growth investors lies not in whether they care about value (sensible investors in both groups do), but where they believe the investing payoff is greater. Value investors believe that it is assets in place that markets get wrong, and that their best opportunities for finding "under valued" stocks is in mature companies with mispriced assets in place. Growth investors, on the other hand, assert that they are more likely to find mispricing in high growth companies, where the market is either missing or misestimating key elements of growth.

The Lead In

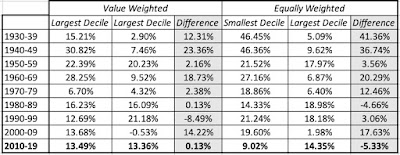

Until the last decade, it was conventional wisdom that value investing beat growth investing, especially over longer time horizon, and the backing for this statement took the form of either anecdotal evidence (with the list of illustrious value investors much longer than the list of legendary growth investors) or historical data showing that low price to book stocks have delivered higher returns than high price to book stocks:

Looking across the entire period (1927-2019), low price to book stocks have clearly won this battle, delivering 5.22% more than high price to book stocks, and this excess return is almost impervious to risk and transaction cost adjustments. Value investors entered the last decade, convinced of the superiority of their philosophy, and in the table below, I look at the difference in returns between low and high PE and PBV stocks, each decade going back to the 1920s.

It is quite clear that 2010-2019 looks very different from prior decades, as high PE and high PBV stocks outperformed low PE and low PBV stocks by substantial margins. The under performance of value has played out not only in the mutual fund business, with value funds lagging growth funds, but has also brought many legendary value investors down to earth. Pushed to explain why, the defense that value investors offered was that the 2008 crisis, Fed interventions and the rise of the FAANG stocks created a perfect storm that rewarded momentum and growth investing, at the expense of value. Implicit in this argument is the belief that this phase would pass and that value investing would regain its rightful place.

The COVID Crisis

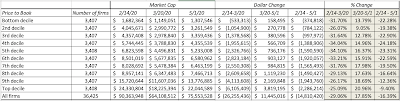

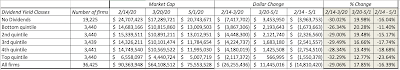

In the early days of the crisis, there were many value investors who viewed at least some of the market correction as punishment for investor overreach on growth and momentum stocks in the past decade. As the weeks have progressed, that argument has been quelled by the cumulating evidence that the market punishment perversely has been far worse for value stocks, i.e., stocks with low PE ratios and high dividend yields than for momentum or growth stocks. To illustrate this, I first look at how the market effects have varied across stocks in different PE ratio classes:

Note that it is the lowest PE stocks that have lost the most market capitalization (almost 25%) between February 14 and May 1, whereas the highest PE stocks have lost only 8.62%, and to add insult to injury, even money losing companies have done better than the lowest PE stocks. I follow up by looking at stocks broken down by price to book ratios:

The results mirror what we saw with PE stocks, with low price to book stocks losing far more value than the highest price to book stocks. I then break down stocks based upon dividend yields:

Low dividend yield stocks and even non-dividend paying stocks have fared far better than high dividend yield stocks. Finally I look at companies, based upon net debt ratios:

Put simply, here is what I see in the data. If I had followed old-time value investing rules and had bought stocks with low PE ratios and high dividends in pre-COVID times, I would have lost far more than if I bought high PE stocks or stocks that trade at high multiples of book value, paying little or no dividends. The only fundamental that has worked in favor of value investors is avoiding companies with high leverage.

A Personal Viewpoint

I believe that value investing has lost its way, a point of view I espoused to portfolio managers in Omaha a few years ago, in a talk, and in a paper on value investing, titled Value Investing: Investing for Grown Ups? In the talk and in the paper, I argued that much of value investing had become rigid (with meaningless rules and static metrics), ritualistic (worshiping at the altar of Buffett and Munger, and paying lip service to Ben Graham) and righteous (with finger wagging and worse reserved for anyone who invested in growth or tech companies). I also presented evidence that it was bringing less to the table than active growth investing, by noting that the average active value investor underperformed a value index fund by more than the average growth investor lagged growth index funds. I also think that fundamental shifts in the economy, and in corporate behavior, have rendered book value, still a key tool in the value investor's tool kit, almost worthless in sectors other than financial services, and accounting inconsistencies have made cross company comparisons much more difficult to make. On a hopeful note, I think that value investing can recover, but only if it is open to more flexible thinking about value, less hero worship and less of a sense of entitlement (to rewards). If you are a value investor, you will be better served accepting the reality that you can do everything right on the valuation front, and still make less money than your neighbor who picks stocks based upon astrological signs, and that luck trumps skill and hard work, even over long time periods.

Active versus Passive Investing

Some of the readers of this blog are in the active investing business and I apologize in advance for raising questions about your choice of profession. After all, any discussion of active versus passive investing that comes down on the side of the latter implicitly is a judgment of whether you are adding value by trying to pick stocks or time markets. Consequently, these discussions quickly turn rancid and personal, and I hope this one does not.

The Difference

In passive investing, as an investor, you allocate your wealth across asset classes (equities, bonds, real assets) based upon your risk aversion, liquidity needs and time horizon, and within each class, rather than pick individual stocks, bonds or real assets, you invest in index funds or exchange traded funds (ETFs) to cover the spectrum of choices. In active investing, you try to time markets (by allocating more money to asset classes that you believe are under valued and less to those that you think are over valued) or pick individual assets that you believe offer the potential for higher returns. Active investing covers a whole range of different philosophies from day trading to buying entire companies and holding them for the long term.

Put simply, active investing covers a range of philosophies with different time horizons, different and often contradictory views about how markets make mistakes and correct them,

The Lead In

Until the 1970s, active investing dominated passive investing for two simple reasons. The first was the presumption that institutional investors were smarter, and had access to more information than the rest of us, and should thus do better with our money. The second was that there were no passive investing vehicles available for average investors. Both delusions came crashing down in the late sixties and early seventies.

-

First, the pioneering studies of mutual fund performance, including this famous one that introduced Jensen's alpha, came to the surprising conclusion that rather than outperform markets, mutual funds under performed by non-trivial amounts. In the years since, there have been literally hundreds of studies that have asked the same question about mutual funds, hedge funds and private equity, using far richer data sets and more sophisticated risk adjustment models to arrive at the same result. You can see Morningstar's 10-year excess return distribution for all active large-blend mutual funds, from 2010-2019, below (with similar graphs for other classes of active mutual funds):

If the counter is that it is hedge and private equity funds where the smart money resides today, the evidence with those funds, once you adjust for reporting and survivor bias, mirrors the mutual fund results. Put bluntly, "smart" money is not that smart, and the advantages that it possesses (bright people, more data, powerful models) don't translate into returns for its investors. Ironically, over the same period, there were hundreds of other studies that claimed to find market inefficiencies, at least on paper, suggesting that there is no internal inconsistency in believing that markets are inefficient and also believing that bearing these markets is really, really difficult to do.

- Second, Jack Bogle upended investment management in 1976 with the Vanguard 500 Index fund, the most disruptive change in the history of the investment business. Over the next three decades, the index fund concept expanded to cover geographies and asset classes, allowing investors unhappy with their investment advisors and mutual funds to switch to low-cost alternatives that delivered higher returns. The entry of ETFs tilted the game even further in favor of passive investing, while also offering active investors new ways of playing sectors and markets.

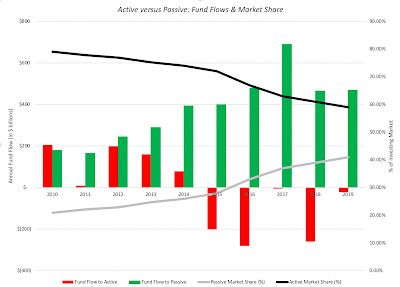

The shift of funds from passive to active has been occurring for a long time, but the shift was small early in the process. In 1995, less than 5% of money was passively invested (almost entirely in index funds) and that percentage rose to about 10% in 2002 and 20% in 2010. In the last decade, that shift has accelerated, as you can see in the graph below:

|

| Source: Morningstar |

The increase in passive investing's market share has come primarily from almost $4 trillion in funds flowing into passive vehicles, but active investing has also seen outflows in the last five years. While some have attributed this to failures of active investors in the last decade, I believe that active investing has been a loser's game, as Charley Ellis aptly described it, for decades, and that the shift can be more easily explained by investors having more choices, as trading moves online and becomes close to costless, and readier access to information on how their portfolios are performing.

The Crisis Performance

Active investors have argued that their failures were due to an undisciplined bull market, where their stock pricing expertise was being discounted, and that their time would come when the next crisis hit. There were also dark warnings about how passive investing would lead to liquidity meltdowns and make the next crisis worse. If active investors wanted to have a chance to shine, they have got in their wish in the last few weeks, where their market timing and stock picking skills were in the spotlight. With their expertise, they should have managed to not only to avoid the worst of the damage in the first few weeks, but should have then gained on the upside, by redeploying assets to the sectors/stocks recovering the quickest. While there is anecdotal evidence that some investors were able to do this, with Bill Ackman's prescient hedge against the COVID collapse getting much attention, I am sure that there were plenty of other smart investors who not only did not see it coming, but made things worse by doubling down on losing bets or cashing out too early.

As we look at the bigger picture, the results are, at best, mixed, and hopes that this crisis would vindicate active investors have not come to fruition, at least yet. I looked at Morningstar's assessment of returns on equity mutual funds in the first quarter of 2020, measured against returns on passive indices for each fund class:

A Personal ViewpointNote that the first quarter included the worst weeks of the crisis (February 14- March 20), and there is little evidence that mutual funds were able to get ahead of their passive counterparts, with only two groups showing outperformance (small and mid-cap value), but active funds collectively under performed by 1.37% during this period. Focusing on market timing skills, tactical asset allocation funds (whose selling pitch is that they can help investors avoid market crisis and bear markets) were down 13.87% during the quarter, at first sight beating the overall US equity market, which was down 20.57%. That comparison is skewed in favor of these funds, though, since tactical asset allocation funds typically tend to invest about 60% in equities, and when adjusted for that equity allocation, they too underperformed the market. Looking at hedge funds in the first quarter of 2020, the weighted hedge fund index was down 8.5% and saw $33 billion in fund outflows, though there were some bright spots, with macro hedge funds performing much better. Overall, though, there was little to celebrate on the active investing front during this crisis. On the market liquidity front, while much has been made of the swings up and down in the market during this crisis, the market has held up remarkably well. A comparison to the chaos in the last quarter of 2008 suggests that the market has dealt with and continues to deal with this crisis with far more equanimity than it did in 2008. In fact, I think that the financial markets have done far better than politicians, pandemic specialists and market gurus during the last weeks, in the face of uncertainty.

I have been skeptical about both the reasons given for active investing's slide over the last decade and the dire consequences of passive investing, and this crisis has only reinforced that skepticism. For active investing to deal with its very real problems, it has to get past denial (that there is a problem), delusion (that active investing is actually working, based upon anecdotal evidence) and blame (that it is all someone else's fault). Coming out of this crisis, I think that more money will leave active investing and flow into passive investing, that active investing will continue to shrink as a business, but that there will be a subset of active investing that survives and prospers. I don't believe that artificial intelligence and big data will rescue active investing, since any investment strategies built purely around numbers and mechanics will be quickly replicated and imitated. Instead, the future will belong to multidisciplinary money managers, who have well thought-out and deeply held investment philosophies, but are willing to learn and quickly adapt investment strategies to reflect market realities.

Small versus Large Cap

The small cap premium was among the earliest anomalies uncovered by researchers in the 1970s and it came from the recognition that small market capitalization stocks earned higher returns than the rest of the market, after adjusting for risk. That premium has become part of financial practice, driving some investors to allocate disproportionate portions of their portfolios to small cap funds and appraisers to add small cap premiums to discount rates, when valuing small companies.

The Difference

There are two things worth noting at the outset about the small cap premiums. The first is that market capitalization is the proxy for size in the small cap studio, not revenues or earnings. Thus, you can have a young company with little or no revenues and large losses with a large market capitalization and a mature company with large revenues and a small market capitalization. The second is that to define a small capitalization stock, you have to think in relative terms, by comparing market capitalizations across companies. In fact, much of the relevant research on small cap stocks has been based on breaking companies down by market capitalization into deciles and looking at returns on each decile. One reason that the small cap premium resonates so strongly with investors is because it seems to make intuitive sense, since it seems reasonable that small companies, with less sustainable business models, less access to capital and greater key person risk, should be riskier than larger companies.

The Lead In

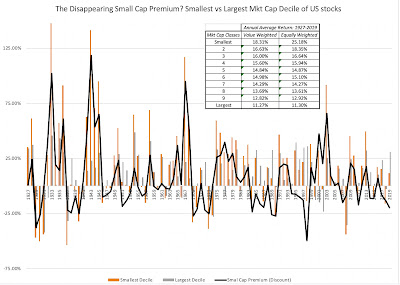

As with value investing, the strongest arguments for the small cap premium come from looking at historical returns on US stocks, broken down by decile, into market cap classes.

Going back to 1927, the smallest cap stocks have delivered about 3.47% more annually than than the rest of the market, on a value-weighted basis. That outperformance though obscures a troubling trend in the data, which is that the small cap premium has disappeared since 1980; small cap stocks have earned about 0.10% less than the average stock between 1980 and 2019. The table below breaks down the small cap premium, by decade:

The data in this table is testimony to two phenomena. The first is the belief in mean reversion that lies at the heart of so many investment strategies, with the mean being computed over long time periods, and primarily with US stocks. The second is that once bad valuation practices, once embedded in the status quo, are very difficult to remove. In my view, the use of small cap premiums in valuation practice have no basis in the data, but that does not mean that people will stop using them.

The Crisis Performance

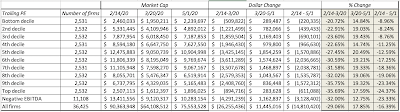

As with active and value investing, there are some who believe that the fading of the small cap premium is temporary and that it will return, when markets change. To the extent that this crisis may constitute a market shift, I examined the performance of stocks, broken down by market capitalization into deciles between February 14, 2020 and May 1, 2020.

I know that it is still early in this crisis, but looking at the numbers so far, there is little good news for small cap investors, with stocks in the lowest two declines suffering more than the rest of the market. In fact, if there is a message in these returns, it is that the post-COVID economy will be tilted even more in favor of large companies, at the expense of small ones, as other businesses follow the tech model of concentrated market power.

A Personal Viewpoint

It is still possible that the shifts in investor behavior and corporate performance could benefit small companies in the future, but I am hard pressed trying to think of reasons why. It is my belief that forces that allowed small cap stocks to earn a premium over large cap stocks have largely faded. I am not arguing that investing in small cap stocks is a bad strategy, but investing in small companies, just because they are small, and expecting to get rewarded for doing so, is asking to be rewarded for doing very little. Markets are unlikely to oblige. It is possible that you can build more discriminating strategies around small cap stocks that can make money, but that will require again bringing something else to the equation that is not being tracked or priced in by the market already.