Written by: Yusuke Hashimoto and Wateru Araiso

The Bank of Japan (BOJ) surprised the market in December 2022 when it doubled its cap on the 10-year Japanese government bond (JGB) from 0.25% to 0.5%, in response to tighter global monetary policies. The widening interest-rate gap between Japan and other developed economies as other central banks tighten has been a growing concern for the BOJ, which has long held an ultra-easy monetary policy. Thanks to that policy, Japanese fixed-income investors have steered away from their home market for decades, seeking the higher yields of global bond markets.

Below, we address two critical questions: First, will Japan exit its ultra-easy policy mode in 2023? Second, in response to BOJ policy actions, will Japanese bond investors shift their holdings out of hedged foreign bonds and into yen bonds?

The Bank of Japan’s Likely Next Steps

Could the BOJ’s past behavior be a guide to its next steps? Historically, the BOJ has modified its monetary policy toward the end of a global policy cycle. For example, during the natural resource boom of the early to mid-2000s, the US and euro area began tightening in 2004 and 2005, respectively, while Japan tightened in 2006, around the time the Federal Reserve finished tightening and just seven months before it started easing.

Unfortunately, whether that pattern holds in 2023 is anyone’s guess, especially with global inflation still not under control. For now, market participants expect the Fed to finish tightening and begin easing later this year, which would imply imminent BOJ tightening. But these market expectations contradict the Fed’s own projections for the policy rate (higher for longer). And we expect the inflation and economic data driving the Fed and other central banks to remain highly variable for much of the year. That doesn’t give us much visibility into the path for the BOJ.

However, we can get a clearer picture by digging into Japan’s unique situation. In Japan, normalization of monetary policy would begin with unwinding two policies that have been in place for close to a decade—negative interest-rate policy (NIRP) and yield-curve control (YCC)—and would eventually entail adopting a more conventional monetary easing policy, such as quantitative easing.

Already, YCC is under pressure. When the BOJ raised the cap on the benchmark 10-year JGB in December, market expectations for the 10-year yield remained above the 0.5% limit, compelling the BOJ to buy up all market inventory of the benchmark bond to preserve the 0.5% cap. This caused liquidity to evaporate and led to the exclusion of some JGB issues from a major global bond index.

To restore liquidity, we expect the BOJ to eliminate YCC before the end of the year. (We think it’s unlikely that, at that point, interest rates will rise above 1% for the 10-year JGB, considering prevailing inflation trends, the correlation between US Treasury bonds and JGBs, and the yield differentials within the JGB market.)

Meanwhile, we expect Japanese policymakers to maintain NIRP, so long as the dollar-yen exchange rate remains below 150. Although transitioning from NIRP to a zero interest-rate policy—a 10-basis-point increase—would theoretically help promote normalization, there aren’t any technical obstacles to maintaining NIRP, and policymakers could continue to use it as a tool for countering any sharp depreciation in the yen, as we saw in 2022.

Thus, the path to higher—and more competitive—Japanese bond yields isn’t likely to be straight.

Japanese Investors’ Preferences Won’t Change Overnight

Predicting whether Japanese investors will shift their holdings out of foreign debt and into yen bonds requires an appreciation of the factors influencing their decision. Japanese investors consider several factors when deciding whether to invest at home or abroad, one of which is the cost of hedging foreign currencies back to yen.

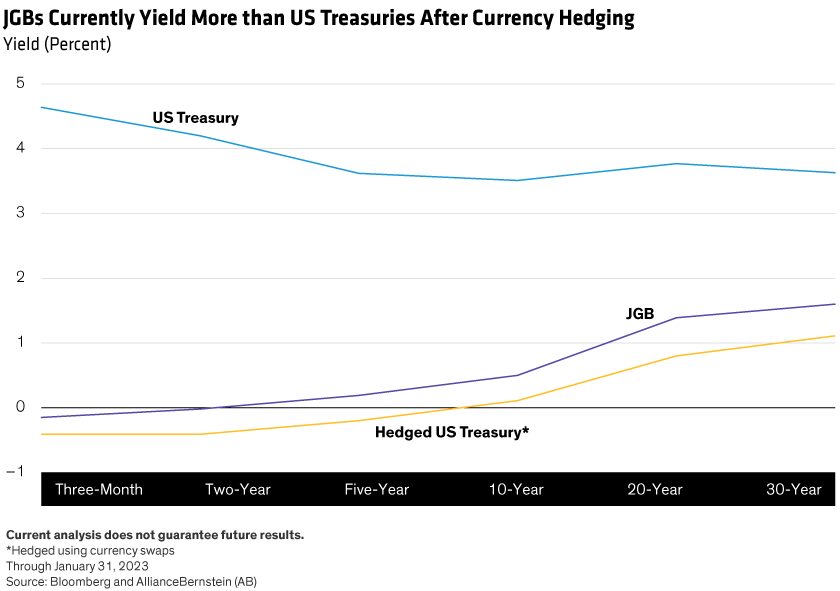

Compare currency-hedged yields. To fairly compare yields on yen bonds to those on non-yen bonds, we must first subtract the cost of a currency hedge. (While there’s more than one method of currency hedging, we prefer the use of currency swaps to mitigate the risk of exchange-rate fluctuations relative to future cash flows. This method is precise and is especially suitable for fixed-income assets, whose future cash flows are predictable. Other currency-hedging techniques may provide somewhat different results.)

JBGs currently yield 25 to 60 basis points more than US Treasuries after currency hedging (Display), suggesting that Japanese investors may consider moving back to JGBs. Investors with ample US–dollar liquidity, such as US banks, also take advantage of such cross-border yield differences. Indeed, most bondholders of shorter-maturity JGBs are non-Japanese investors.

Consider the broader universe. While the hedged yield difference between government bonds currently favors Japan, this doesn’t hold true when comparing yields on corporate issuers.

In fact, Japanese corporate issuers’ yen-denominated credits don’t yield much more than comparable-maturity JGBs. That’s because, in a low-interest-rate country like Japan, desperation for income drives local investors into yen-denominated corporate bonds with any decent yield, effectively keeping yields low, in a vicious cycle spun by home-country bias.

At the same time, when Japanese firms raise funds in currencies other than the yen, they lose the advantage of home-country bias and must issue bonds at wider credit spreads. For example, the leading Japanese issuer, Toyota Motor, issued a USD bond due in September 2027, with a coupon of 4.55%. As of February 17, this bond, once hedged into yen, yielded 0.60%. By contrast, the Toyota JPY bond due October 2027 carries a 0.265% coupon and yielded only 0.44%.

What’s more, because few non-Japanese firms issue yen bonds, the yen credit market remains small. As a result, hedged foreign bonds typically provide Japanese investors with a bigger, higher-yielding universe of credits to choose from.

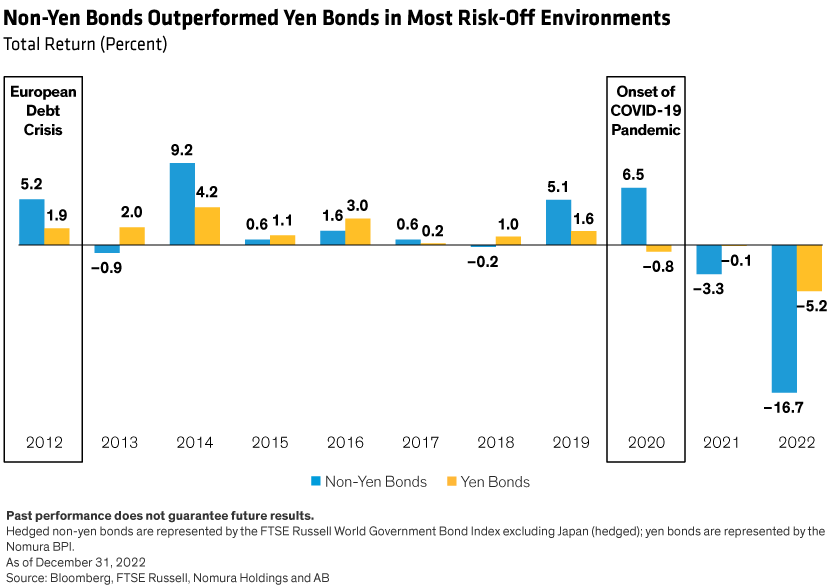

Consider investor objectives. Investors value bonds for their role as a “safe haven” when equity markets are in crisis; government bonds tend to perform well when stocks misbehave. But because the BOJ is the biggest player in the JGB market, the yen market is less sensitive to the risk environment.

As a result, when we compare the historical returns of hedged non-yen bonds to those of yen bonds, we see that non-yen bond returns have often been significantly higher than yen bonds during market upheavals (Display)—a pattern that puts yen bonds at a slight disadvantage to non-yen bonds in the eyes of investors.

Will Investment Flows Increase to Japan?

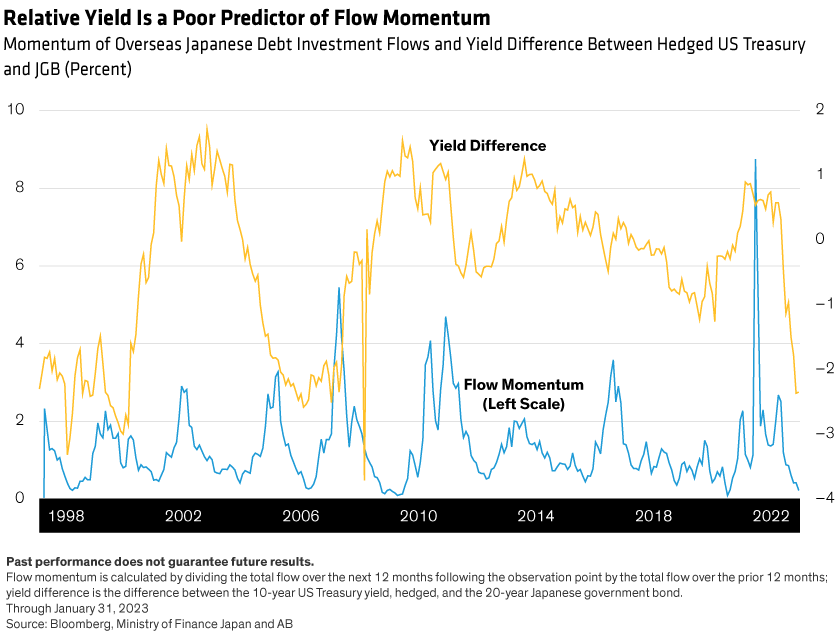

As the gap grows between Japanese policy rates and those of other countries, so too does the cost of hedging currency for Japanese investors. It’s reasonable, then, to speculate that Japanese investors may sell foreign government bonds. But it’s not a sure thing. When we look at the history of Japanese overseas debt investment flows, we see that the flow volume cycles more quickly than rate levels (Display). There’s even been a temporary increase in flows during expensive hedging environments, such as 2005 and 2016, when the US was hiking rates.

To us, this suggests that investment objective is a more critical criterion for Japanese investors than yield differential. For Japanese investors seeking “safe” assets or deploying bonds as an anchor to windward in a broader asset allocation, non-yen bonds remain a reasonable choice.

Regardless, the decision about whether foreign or domestic markets serve the investor better is a complex one that’s highly dependent on unique investor needs, investment techniques and objectives. That’s why, in our view, Japanese investors’ behavior won’t change as easily as policy rates do—and Japanese investors aren’t likely to surge back into home markets in 2023.

Related: The Road to Decarbonization Is Bumpy. Carbon Allowances Can Help.