Written by: Salima Lamdouar and Tiffanie Wong

We’re optimistic that securities labeled as environmental, social and governance (ESG) bonds will help create a better, more sustainable world. And investors are just as eager to buy these bonds. But with the recent proliferation of ESG bond structures, the investment landscape has become more complex—and potentially confusing.

Assessing an ESG-labeled bond means delving deeper than an issuer’s financials, into the bond’s governing framework and its fit with the overall sustainability of the issuing company. In other words, to make the right investment choices, investors must understand the different structures and their investment implications.

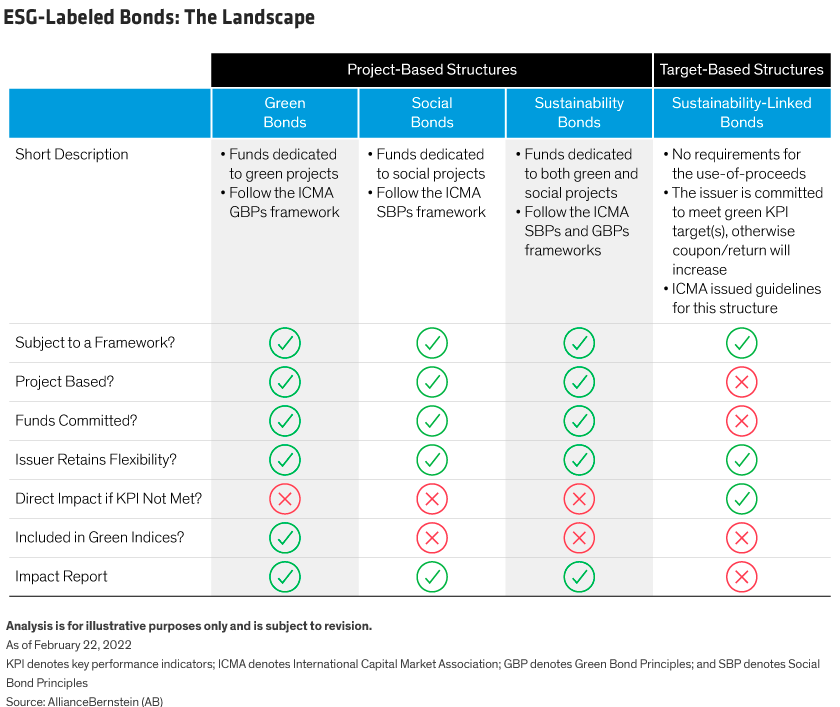

Many investors are already familiar with green bonds, which have been on the market since 2007. Green bonds finance a specific project or projects with an environmentally beneficial purpose. Since then, companies have issued new types of bonds to finance a range of green, social and sustainable projects (Display).

The most recent innovation—the sustainability-linked bond—is a target-based structure incorporating key performance indicators (KPIs). It incentivizes the issuing company to achieve higher ESG standards across the business, rather than to finance a specific project. Such initiatives give issuers considerable flexibility in raising capital on ESG-linked grounds.

The proliferation of ESG-linked bonds means investors need to be aware of the technical distinctions and the investment implications of each type.

Project-Based Structures

Despite the growing popularity of more recent structures, green bonds are still the biggest class of ESG-linked finance, with more than $1 trillion outstanding, according to the Climate Bonds Initiative. We like this structure because it supplies a clear link between capital investment and improving the environment, and it works well for many industries.

Even so, there are several intricacies that investors should bear in mind. Proceeds for each issue are meant to finance a green project (or range of projects) in line with a specified framework and timeline. But bondholders cannot force the issuer to use the proceeds for the stated projects or to deliver them on time. Effectively, investors in green bonds are relying on the reputation of the issuing company and must have confidence in its credentials.

Importantly, investors should be sure that the issuer’s projects are genuinely environmentally beneficial and not misrepresented, or “greenwashed.” That means verifying that the metrics established for a project’s impact report are specific, material and credible. For example, investors might determine whether a project that aims to reduce CO2 emissions will do so by a meaningful amount.

One development that helps frame certain types of impactful projects comes from Europe. The European Union (EU) has created a detailed taxonomy for sustainable activities that investors can refer to when authenticating green bond issues related to climate change mitigation and adaptation. Whenever possible, green bonds’ use of proceeds should align with the EU taxonomy. For euro-area companies—particularly high-yield issuers—that have been shy about issuing green bonds, this is welcome news, as the taxonomy allows them to identify green assets more easily.

We are closely watching similar developments in other regions, such as China. In the meantime, the leading index providers have established their own tests to determine whether bonds are genuinely green, though these can be subjective and aren’t exhaustive. As a result, inclusion in a green bond index doesn’t prove that a bond is truly green.

Social bonds work the same way as green bonds but finance socially impactful projects. Examples include new buildings for communal benefit, educational programs for an underprivileged demographic and more hospital beds for low-income areas.

We saw a resurgence in activity in this asset class in 2020, with issuers such as Italian national agency Cassa Depositi e Prestiti using this structure to help respond to the COVID-19 emergency and sustain the recovery of the Italian economy and communities.

Other project-based structures include sustainability bonds and sustainable development goal (SDG) bonds. Use of proceeds for sustainability bonds falls into both social and environmental categories, while for SDG bonds, the pool of eligible assets can be wider and align with one or more United Nations SDG.

Just as with green bonds, investors need to do due diligence on all project-based bond issuers and the credibility of their projects.

Target-Based Structures

The proceeds of sustainability-linked bonds (formerly called KPI-linked bonds) are meant for general corporate purposes, not for a specific project. 2021 saw a big uptick in this kind of issuance, as flexibility around use of proceeds opened the door for many high-yield and emerging-market issuers, some of which are in “dirty” industries and are transitioning to more climate-friendly processes.

Sustainability-linked bonds are based on a KPI at firm level. If the company fails to achieve the KPI within the specified timeline, it is penalized with a coupon step-up on the bond. Accordingly, investors must research the company’s overall sustainability strategy and determine whether the KPI aligns with that goal.

For sustainability-linked bonds, there is a direct and enforceable monetary incentive for the issuer to perform, rather than reputational risk only. This type of structure makes the issuing company accountable for executing on a top-down strategy that materially changes the sustainability of the business, as opposed to simply identifying and segregating a set of green assets while continuing with business as usual for its other activities.

That’s why we like certain sustainability-linked structures. We think, for instance, that greenhouse gas KPIs that are aligned with the 2 Degrees Investing Initiative are well suited for high-emitting sectors such as energy, cement and some chemicals manufacturers.

One possible reservation about sustainability-linked structures is that investors benefit from the coupon step-up if the issuer fails to hit its target. While some see this as a misalignment of incentives, we view it like step-ups that result from a credit downgrade—we don’t want the downgrade to happen but expect to be compensated if it does. In the future, sustainability-linked structures may be developed with different issuer incentives that further improve alignment with investors’ objectives.

That said, sustainability-linked structures need to be monitored for greenwashing, given the inherent flexibility around use of proceeds. KPIs must be chosen and calibrated carefully. And investors should actively engage with the issuer to get progress updates on achieving the KPI and to better understand the tools used to meet it.

Due Diligence Still Key in Evolving ESG-Labeled Bond Market

While investors now have a wide range of ESG-labeled bonds to select from, they need to conduct thorough due diligence—to analyze the specifics of each bond’s structure and to understand how it supports the overall sustainability strategy of the issuing company. Identifying the right choice will also depend on the investor’s particular investments and ESG approaches.

But investors can be confident that the market is continuing to evolve to supply more choices and better accountability.

Related: How Advisors Can Bring Green to Client Muni Positions