Written by: Jenny Zeng and Hua Cheng

Recent bond defaults by state-owned enterprises (SOEs) have roiled China’s typically calm onshore corporate bond market. Regulators acted quickly to provide liquidity and calm market jitters. But should investors be worried?

Policymakers Have “Zero Tolerance” for Corporate Misbehavior

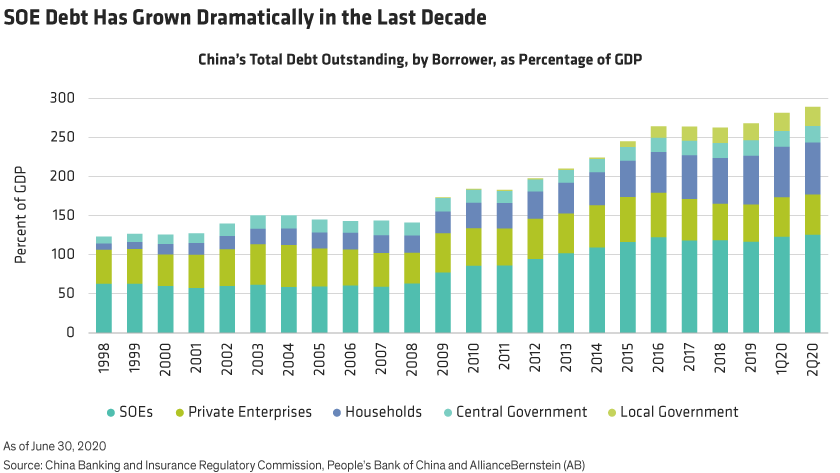

Historically, China’s local governments intervened to prevent defaults, bailing out weak issuers to avoid job layoffs and ensure market stability. This created the effect of an implied guarantee on corporate bonds and allowed SOE total debt to balloon to nearly 130% of GDP today (Display).

But the perception of an implied guarantee had been eroding over the last several years, as China shifted to a policy of bad-debt cleanup. The cleanup began in 2014 when China allowed its first onshore corporate bond default: Shanghai Chaori Solar Energy. Its first SOE default—Baoding Tianwei Group—took place in 2015. Over the next few years, China’s cleanup policy slowly gained momentum—that is, until the Covid-19 pandemic forced policymakers to shift into forbearance mode in support of economic recovery.

Now that China’s recovery is strong and broad, policymakers are again allowing orderly defaults, but this time there’s a twist. When Yongcheng Coal & Electricity, a local SOE in Henan province, missed its November coupon payment, market reaction reflected concerns that SOEs might be purposely evading their debts. In other words, Yongcheng’s default appeared to be a case of unwillingness to pay, rather than inability to pay.

The Financial Stability and Development Commission (FSDC), a high-level coordinating body chaired by Vice Premier Liu He, publicly declared that it had “zero tolerance” for illicit corporate behavior. A chastened Yongcheng subsequently announced that it had reached an agreement with its creditors to repay half the principal owed up front and the remaining principal and interest owed nine months later.

Regulators’ swift market intervention suggests that they are keen to keep financial risks under control over the near term. But it’s clear that the days of an implicit guarantee for local SOE debt are over and that expectations of government bailouts will continue to erode.

Beijing Targets Healthier Credit Markets

In the view of China’s top authorities, breaking the implicit guarantee is critical for the long-term healthy development of its credit markets. The 2015 SOE reform plan asserts that SOEs are responsible for their own profits and losses and must “bear their own risks.” Other policy documents call for a “strict separation” between local government financing vehicles (LGFVs) and local governments. And People’s Bank of China Governor Yi Gang recently wrote, “We should gradually break the implicit guarantee, so that…the mismatch between the nominal and the actual bearer of risk for some financial assets is corrected.”

As China’s commitment to a more market-driven allocation of capital plays out, differentiation between credits will intensify, providing investors with more choices across the risk spectrum. Efficient pricing also acts as a structural pillar to better attract foreign capital.

Indeed, potential inflows from outside of China could be considerable. At US$15 trillion, China is the world’s third-largest debt market, yet foreign investors still account for only about 3% of total market share, and their participation has been concentrated in Chinese government and policy bank bonds.

Foreign investment is expected to rise. Chinese government bonds are now included in major global debt indices, including the Bloomberg Barclays Global Aggregate Index (which also includes policy bank bonds) and J.P. Morgan Government Bond Index Emerging Markets. Both are popular benchmarks for passive funds.

Additionally, interest rates are likely to stay low or even negative globally. In contrast, China’s real rates remain positive, and its debt trades at a significant yield premium to developed-market debt. These relatively high yields should continue to attract income-hungry foreign investors.

For foreign investors to meaningfully broaden their onshore China fixed-income exposure into the SOE and wider credit markets, we believe further development—such as credit differentiation and greater transparency—will need to be addressed. Secondary market liquidity is also challenging.

No Signs of Systemic Risk Ahead

There will almost certainly be more bond defaults by local SOEs—including LGFVs—in 2021. More defaults could trigger further bond repricing and make it even tougher for SOEs to refinance.

China is thus balancing its policy of tolerance for defaults against the increased risk of social unrest and/or financial market instability. At the end of the day, maintaining financial stability is among China’s highest priorities.

Because China has both the desire and the tools to avoid massive financial contagion, we don’t think SOE bond defaults signal a major systemic risk for China’s economy. In our view, today’s liquidity levels are adequate, and top-down communication out of Beijing—which continues to focus on stabilizing macro leverage—is effective at preventing a snowball effect.

Such a backdrop favors well-managed companies. In a more open market, Beijing’s tolerance for allowing SOEs to fail facilitates a more rational distribution of capital and should lead to yield spreads between private and state-run companies that better represent actual risk.

The takeaway? Investors should remain selective and risk-aware but engaged in Chinese credit. To our minds, allowing SOE defaults alongside rising yields reflects Beijing’s confidence in the economic recovery and heralds a healthier and more dynamic Chinese credit market in the months and years ahead.