Written by: Scott DiMaggio and Gershon Distenfeld

Low yields plus rising defaults seemingly leave little ground for bond investors seeking safety or income—or both. But for investors who remain flexible, these objectives aren’t as distant as many think.

Markets Didn’t Stay Down for Long

March 2020 was among the most challenging periods in the history of the bond markets, as fallout from the coronavirus pandemic derailed a global economy already experiencing tepid growth.

Credit spreads blew out to their widest levels in a decade, and at unprecedented speed. Liquidity evaporated. Oil prices plunged. And bond investors found they had nowhere to hide outside of government debt—and US Treasuries in particular.

In early April, we forecast that the credit markets were more likely to snap back than to gradually return to normal. The second-quarter rebound was even faster than we expected, thanks largely to a swift and massive global fiscal and monetary policy response that included easing of key rates and highly supportive bond purchases.

As hoped, this policy response restored stability and liquidity to the global bond markets and led to a reversal in spreads on risk assets in the second quarter. US high-yield spreads versus Treasuries, for example, narrowed roughly 500 basis points from their peaks—though they remain above January levels. A surge in new corporate issuance found so many enthusiastic buyers that offerings were frequently oversubscribed.

But the recovery hasn’t been uniform. Investment-grade corporate bonds saw the fastest rebound, with spreads now close to their 10-year averages. High-yield corporates, emerging-market debt (EMD) and US credit-risk–transfer (CRT) securities aren’t far behind. And US commercial mortgage-backed securities (CMBS), with their heavy exposure to retail, have begun to rebound too.

Duration Still Matters, Despite Low Yields

Meanwhile, central banks are anchoring key rates at historic lows. Investors worry that today’s low yields will limit downside protection going forward. They’re concerned that government bonds will have less room to rally during risk-off periods—and that returns will be commensurately curtailed. This fear is especially prevalent in the US, where 10-year Treasury yields below 1% are new territory.

But historical experience shows that low or even negative yields do not eliminate the buffer provided by holding duration (interest-rate risk). During the most recent downturn, at a time when German Bund yields were –0.5%, an allocation to government bonds significantly muted the credit downdraft. Over February and March, a hypothetical portfolio comprising 50% 10-year German Bunds and 50% euro high yield fell 7.6%, compared with the Bloomberg Barclays Euro High Yield Index at –15.0%.

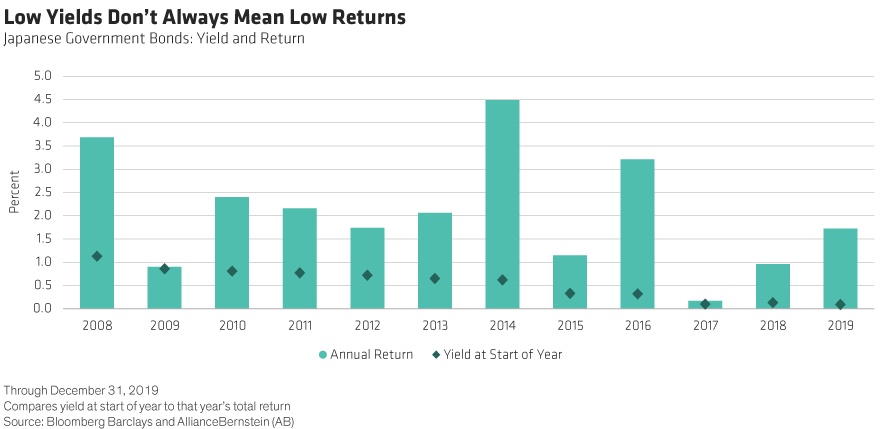

Nor do low yields necessarily translate into low returns. Japan, for instance, has a long history of extremely low yields (Display). For 11 of the last 12 years, the yield on the 10-year Japanese government bond was less than 1%. In contrast, returns over the same period averaged more than twice as much and, in fact, rarely matched starting yield levels.

Accordingly, we believe it’s a mistake to forgo interest-rate risk, particularly with further volatility likely in the months to come.

Credit Looks Compelling, Even as Defaults Rise

We think continued central bank support and ultralow government bond yields will drive strong demand for higher-yielding credit sectors, even as fundamental conditions appear to deteriorate in the corporate market.

And investors should prepare to see more bond downgrades and defaults this year. In April, we expected the US high-yield default rate to exceed 10% over the next 12 months. Since then, many weaker corporations have defaulted. As a result, we now expect the 12-month forward default rate to average 6% to 9%. Global default rates will likely be somewhat lower.

But high default expectations aren’t a sign that a credit apocalypse is coming. Instead, defaults lag instigating events such as recessions and tend to be well signaled through market pricing for months—sometimes years—in advance. In other words, by this time, potential losses and recoveries are already baked into the price. It’s common, in fact, for a credit rally to couple with high default rates, as both tend to follow a cyclical downturn.

So what can yield-hungry investors expect in return over the next few years?

For credit sectors in general and for high-yield corporates in particular, investors can expect to clip the coupon. Forty years of data show that, while the average yield to worst on the US high-yield sector is not a good predictor of return over the next six to 12 months, starting yield has mapped almost perfectly to return over the subsequent five years. That relationship has held through nearly every kind of market environment.

In our view, with valuations still above long-term averages and the technical picture a positive one, investors should consider leaning into credit risk as the global economy heals and spreads continue to compress.

Today, investors can find opportunities to enhance yield and potential return by diversifying into:

- Select BBB-rated corporates, including midstream energy companies that are more insulated from oil-price volatility than are other energy issuers;

- Fallen angels, which tend to rebound sharply after downgrade below investment grade;

- Financial credits, such as subordinated (AT1) European bank debt;

- EMD—mostly dollar-denominated sovereign debt, but also corporates;

- CRTs, given healthy US housing-market fundamentals;

- and CMBS, where participants continue to worry about the impact of the pandemic on commercial real estate, as we collectively reevalute how we live, work and shop. In our analysis, CMBS yields more than adequately compensate investors for expected losses due to the decline of retail as well as adverse pressures from the pandemic.

Lastly, given today’s uncertain environment, be selective; fundamentals matter.

Manage Interest-Rate and Credit Risks Together

Investors who strike a balance between interest-rate risk and credit risk—and then dynamically manage that balance—can expect to achieve both downside protection and efficient income.

That’s because the two asset classes are negatively correlated during risk-off environments, just when a buffer is needed most. In other words, safety-seeking assets, such as government bonds, tend to do well when return-seeking assets, such as high-yield corporates, have a down day.

We expect occasional down days in the second half of 2020 as countries emerge from lockdowns and global economic activity resumes. But don’t forgo exposure to rate and credit risks because of low yields and rising defaults. Investors who stay the course in fixed income can expect their bond portfolios to provide ballast, yield and healthy return potential as the trend toward a full recovery continues.