Written by: Tom O’Shea, CFA | Innovator

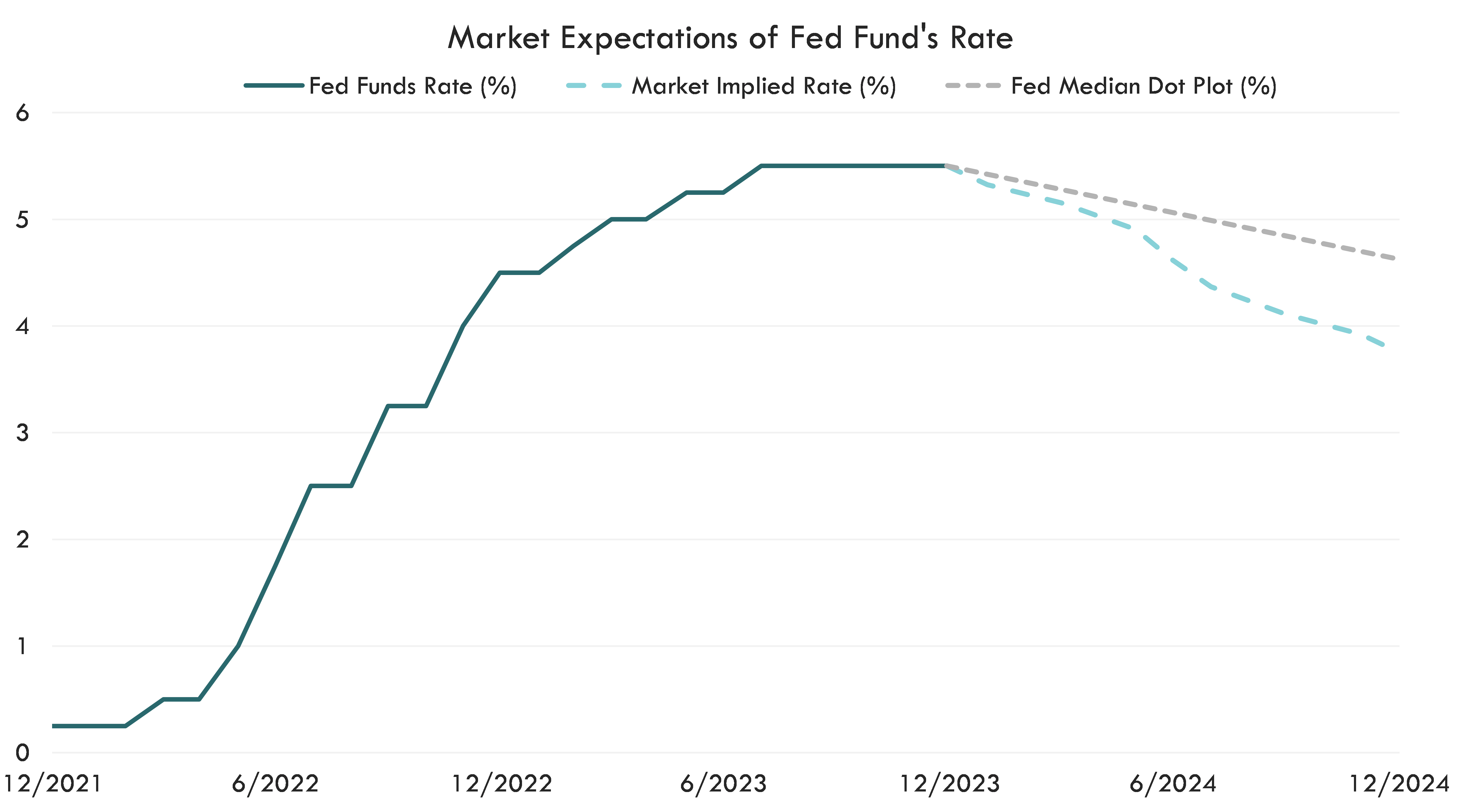

In navigating the intricate dance of monetary policy, Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell exhibited a measured approach throughout the 2022 tightening cycle and subsequent pause. Powell’s comments aimed to prevent the loosening of financial conditions and the higher consumer prices that would accompany them. Federal Reserve officials changed their tune during the December 2023 FOMC meeting when they mentioned the possibility of as many as three 0.25% rate cuts in 2024, with the first coming as soon as March. As a result, U.S. equities climbed 2.7% to close out 2023, and markets began pricing in about six rate cuts by the end of 2024.

But the Fed began its rate hike campaign much too late. As futures markets price in dovish monetary policy, the Fed runs the risk of cutting rates prematurely before restrictive policy has had sufficient time to steer inflation back to the Fed’s 2% target.

Source: Bloomberg L.P. The Fed Funds rate is the upper bound. Fed Median Dot Plot as of 12/13/2023. Market Implied Fed Funds rate as of 1/16/2024. Fed Funds data from 12/31/2021 - 12/31/2023.

Is the Fed Considering Cutting Too Early?

In our 2024 outlook, we foresaw a year-long pause by the Federal Reserve, grounded in the conviction that a robust labor market and buoyant consumer spending would require restrictive rates to hold at current levels. Our analysis held that inflation had not decreased to a level where Fed officials could ignore the geopolitical risks around the Ukraine-Russia and Israel-Gaza conflicts. The Houthi rebel attacks on commercial ships in the Red Sea further fueled inflation pressures.

Some Fed officials have acknowledged that their December comments may have been premature, but markets are still pricing in significant cuts in 2024. December’s hot CPI print and strong retail sales figures shifted expectations of a March rate cut from about 80% the Friday before Martin Luther King, Jr. Day to just over 40% on January 22. While the likelihood of a March rate cut appears to be diminishing, we find it prudent to delve into historical cutting cycles to better inform capital allocation in the current environment.

Timing the Fed’s First Cut

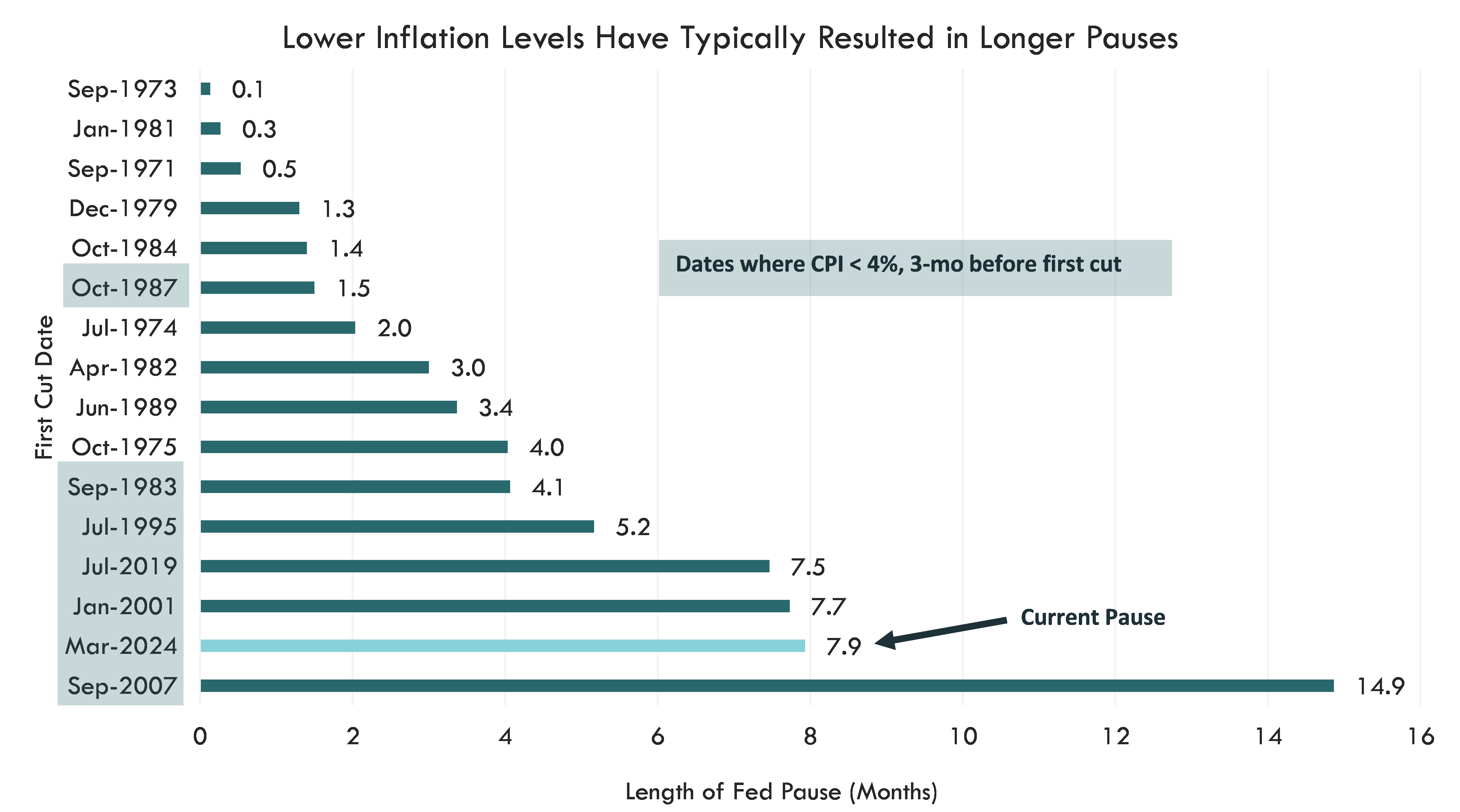

Examining the historical data on Federal Reserve pauses dating back to 1971 reveals a diverse range, spanning from as brief as four days to nearly 15 months. We found that similar cycles where inflation remained below 4% year-over-year, averaged about seven months. As we approach the March 2024 FOMC meeting, the prospective duration of this pause stands to become the second-longest in history.

Source: Bloomberg L.P.

Determining when to cut is complicated by the Federal Reserve’s dual mandate of stabilizing prices and maximizing sustainable employment. A strong labor market, mirroring current conditions, allows the Fed to maintain restrictive policy for an extended duration. Analyzing three cycles with an unemployment rate below 4.5% in the three months preceding the inaugural cut reveals an average pause of 10 months. Save 2019’s cycle, the current cycle ranks near the lowest in terms of initial jobless claims and continuing claims.

Based on the Fed’s history of pause lengths and the current labor market, we believe that the current pause has room to extend. Right or wrong, investors should understand how to position themselves as the Fed considers lowering rates.

Portfolio Positioning

Whether the market eventually experiences a hard or soft landing, equities typically rally for the period following the last hike of a tightening cycle, buoyed by investor enthusiasm that strict monetary policy is behind them. This enthusiasm recently contributed to the S&P 500 reaching new all-time highs. But what can investors expect as Fed officials shift to cutting rates? The Fed reduces rates as a stimulative measure to combat slowing economic growth. While a few instances of "soft landings" exist, in which the Fed preemptively cuts rates before the economy faces significant challenges, more often than not, rate cuts are a reactive response to a swiftly deteriorating labor market or an economy teetering towards recession.

The real-time assessment of whether the Fed's rate adjustments are appropriate adds an additional layer of complexity, underscoring the critical role of proper asset allocation. An analysis of the three months leading up to the first rate cut reveals that U.S. equities were positive less than half the time, with returns ranging from a dismal -27% to a modest 10%. In contrast, bonds performed more resiliently, boasting positive rates exceeding 70% and returns ranging from -4.3% to a commendable 8.8%. Notably, in the lead-up to rate cuts, bonds have outperformed stocks slightly more than half the time, emphasizing the considerations that investors must navigate during rapidly changing market environments.

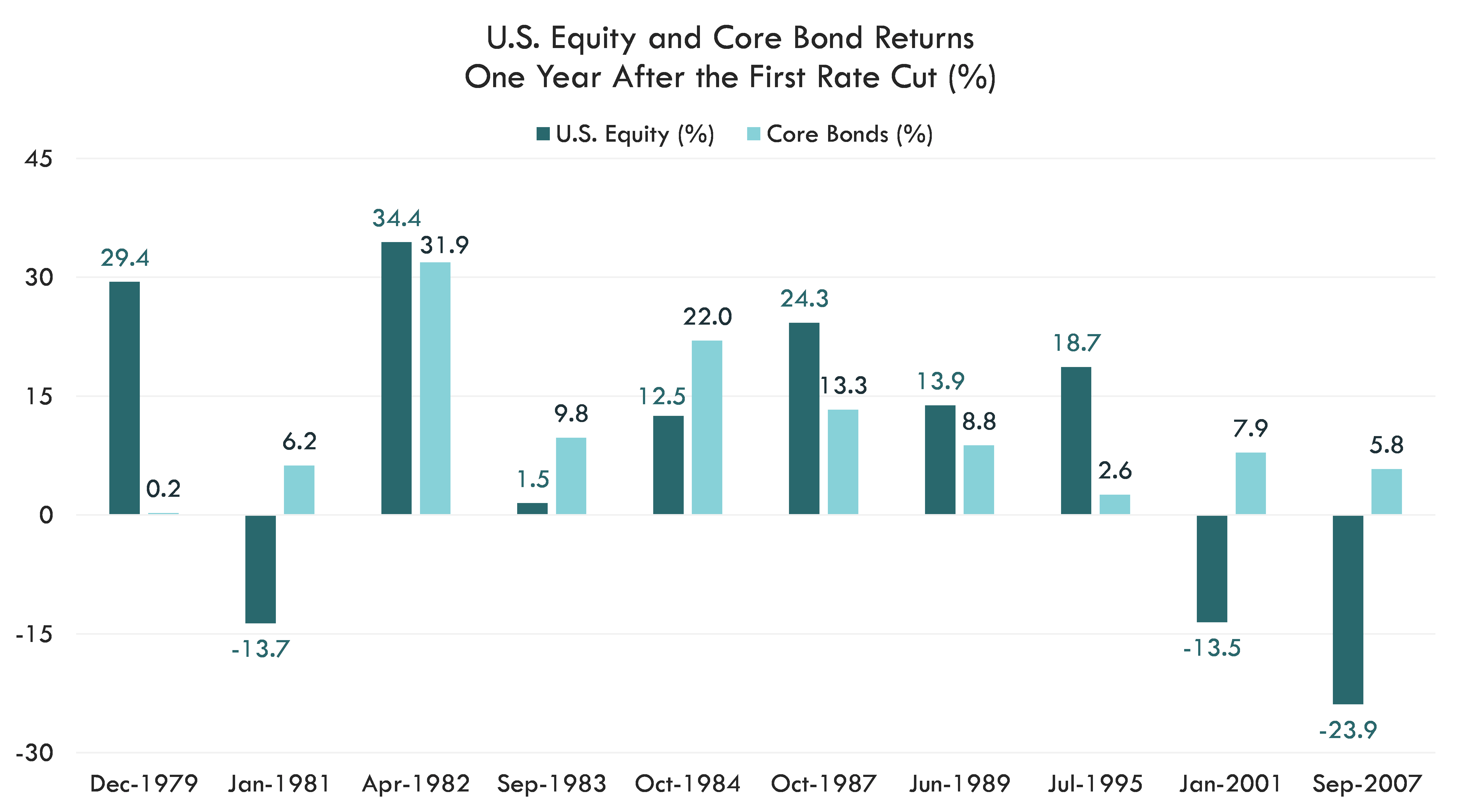

Source: Bloomberg L.P. U.S. Equity represented by the S&P 500 Index. Core Bonds Represented by Bloomberg U.S. Aggregate Bond Index. Once cannot invest directly in an index. Past performance does not guarantee future results. Asset class comparisons are shown after Core Bonds inception (1/1/1976).

Once the Fed actually cuts rates, a consistent trend emerges: core bond prices have been positive 100% of the time in the year following the initial cut. Bonds, boasting a historically impressive success rate, have proven to be a reliable asset class. This reliability has led prudent investors to allocate to long-duration bonds to further boost returns.

However, abstaining from allocating to U.S. equities would have resulted in missed growth opportunities in approximately half of the instances, as we can see in the above chart. If historical patterns hold, a strategic allocation to bonds becomes instrumental in risk management and portfolio growth, especially as investors try to determine if the Fed has managed a soft landing.

Buffered equity positions offer another appealing diversification option, as they allow for upside participation to a cap while providing known levels of downside risk mitigation—which will be especially important if the Fed mismanages policy as seen in January 1981, January 2001, and September 2007.

The Bottom Line

Even in the time when the Federal Reserve messages its policies well in advance, we live in a world where markets can change quickly. Market participants are hoping the Fed can achieve a soft landing, but walking the tightrope of maintaining a healthy labor market and keeping a lid on inflation poses a significant challenge.

Related: Making Higher-Income People Pay for Social Security Shortfalls