Written by: John Lin and Jenny Zeng

China’s 2060 carbon-neutral framework not only addresses climate change, but also discreetly reveals how Beijing envisions the country’s economic future. As efforts to generate more sustainable growth progress, the transition to a greener economy will create diverse new investment opportunities.

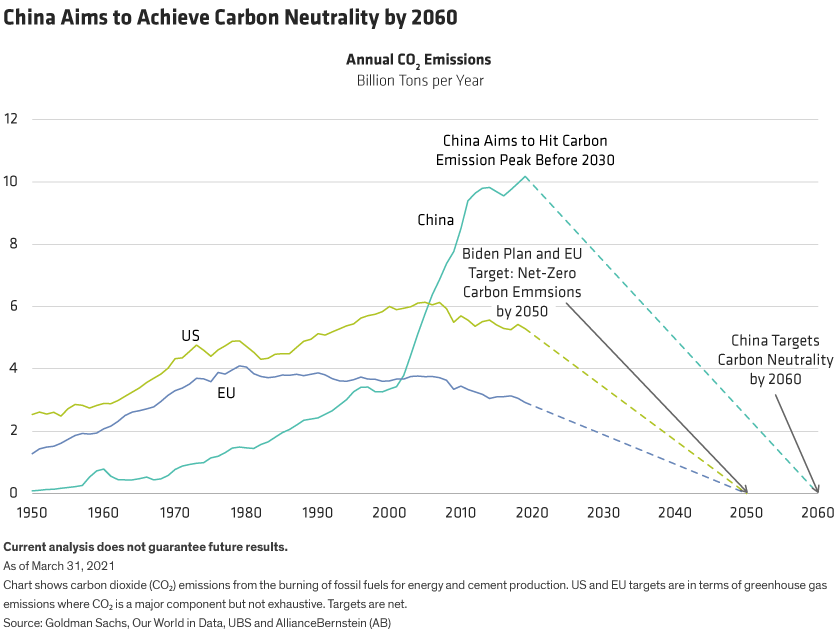

During last September’s UN General Assembly, President Xi Jinping announced two major environmental initiatives for China. First, the world’s second-largest economy is targeting peak carbon dioxide (CO2) emission levels by 2030. Second, China will transition towards carbon neutrality (net-zero CO2 emissions) by 2060.

Full policy details are pending. But, by identifying its arrival destination and announcing the multi-decade time frame, Beijing has joined growing international efforts to combat global warming. Green agenda proponents welcomed the news, as China produces more than a third of global CO2 emissions. Without Beijing, the world will struggle to mitigate greenhouse gas emissions.

For investors, the implications are too big to ignore. China’s 2060 campaign lays out how Beijing sees the country’s manufacturing landscape evolving over the next 40 years. However, given the immediate uncertainty and lack of clarity on how these green initiatives will be rolled out, investors will need to keep a close eye on the details as they unfold.

Sounds Familiar, but Slightly Different

Critics warn that China’s past environmental pledges have disappointed. Beijing’s previous attempts to reduce carbon intensity have often fallen short amid periods of economic crisis. Indeed, during the coronavirus pandemic last year, Beijing reverted to an old playbook by pushing heavy infrastructure spending and removing pollution curbs to keep factories open to prevent massive job losses.

Skepticism is warranted. But while China’s war on pollution is not new, its weapon of choice is. This time, the central government appears to be setting a calculated political agenda to achieve its goals. The 2060 campaign expands the decision-making beyond central ministries down to state and city government officials, reflecting the political depth for this green environmental campaign.

China’s carbon neutrality also coincides with political ambitions for technological self-sufficiency. With wages rising and the workforce shrinking, restructuring for a greener power generation mix is increasingly vital. Such ambitions will permeate across industries, redefining “made in China” to become synonymous with higher-value manufacturing and innovative independence from the West.

How Will Carbon-Neutral Policies Be Implemented?

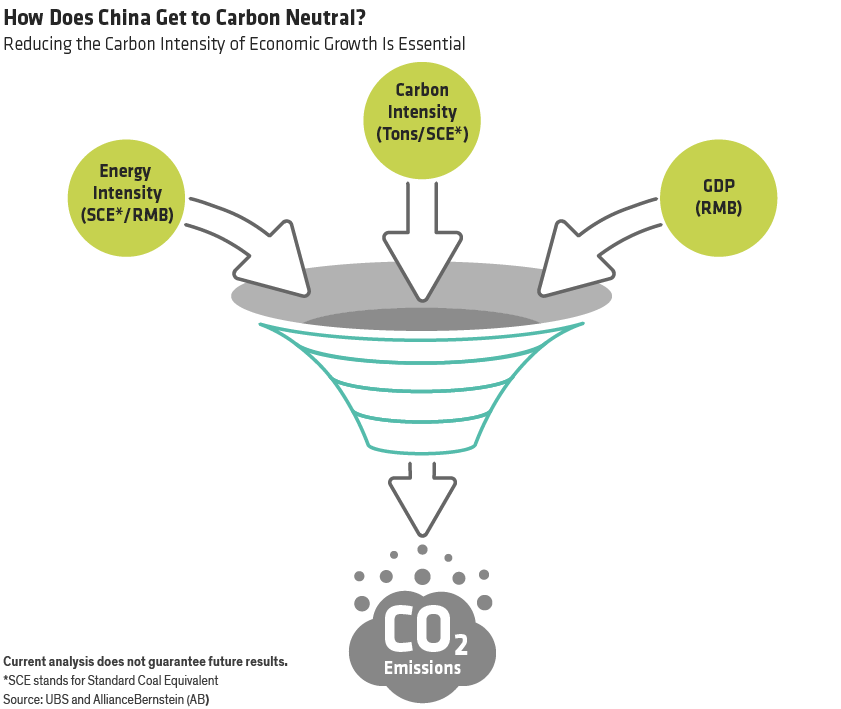

While details are still sparse, we’re already getting a sense of what implementation might look like by 2030. Economic growth will remain a priority, but we expect a stronger policy push to decrease the carbon intensity of that economic growth (Display).

In our view, the following actions taking place now will help establish the multi-decade strategy going forward:

- Curbing Industrial Emissions—China has already begun cutting emissions from the most polluting industries and closing smaller, less-efficient factories.

- Promoting Green Power—By replacing the current power generation infrastructure, more sustainable energy sources such as solar, wind and hydrogen will be incorporated.

- Facilitating Cleaner Transportation—While electric vehicle adoption is proceeding rapidly, the transition away from internal combustion engines cannot completely solve China’s carbon problems, especially if electricity is generated primarily from coal burning.

Investors face multiple pathways to China’s 2060 ambitions; however, few roads will be direct. While many policies will be executed independently, we believe Beijing’s overall green agenda will spill over into other economic policies, reflecting the country’s broader commitment to lowering carbon emissions.

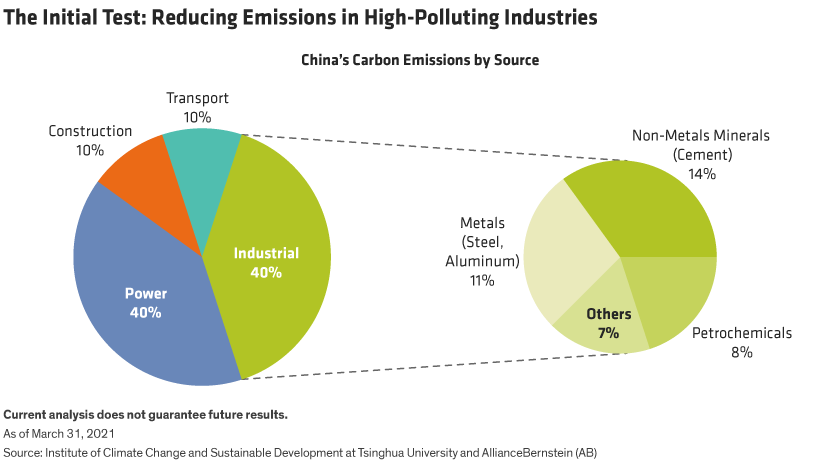

Curbing high-polluting industries serves as an initial test, in our view. With the industrial sector accounting for 40% of China’s CO2 emissions (Display), capacity cuts to coal, aluminum or steel processing will act as early harbingers of how Beijing plans to reach its twin environmental targets over the coming decades.

Production curbs are by no means low-hanging policy fruit. Implementation is often entangled with political challenges, as closing any existing facilities threatens to produce mass unemployment. However, we believe policymakers are aware that delaying carbon emission cuts will inevitably inflate the challenges in the future.

Industrial production curbs and a recovery in global demand from last year’s coronavirus-induced slump has resulted in a steepening commodity supply cost curve. Prices for steel, aluminum and polyethylene are climbing, as producers continuously work towards more efficient use of research and development. As a result, larger and more efficiently run industry leaders will likely consolidate market share.

Building Greener Infrastructure

The success of transitioning away from higher-polluting energy industries will be determined by the availability of viable alternative energy sources. This should deliver a pickup in investment in the nation’s power grid, addressing the historical challenge of building an electrical industrial base robust enough to withstand cyclical demand surges.

With more than 80% of carbon emissions attributed to power generation and industrial production, we believe solar-generated electricity provides that viable step. Solar electricity costs are now on par with coal-fired power generation in many provinces, creating the economic incentives for change. More than just the largest consumer of solar equipment, China also controls roughly three-quarters of the world’s solar manufacturing supply chain. As a result, the industry is well positioned to support other economies pursuing their own carbon-neutral agendas.

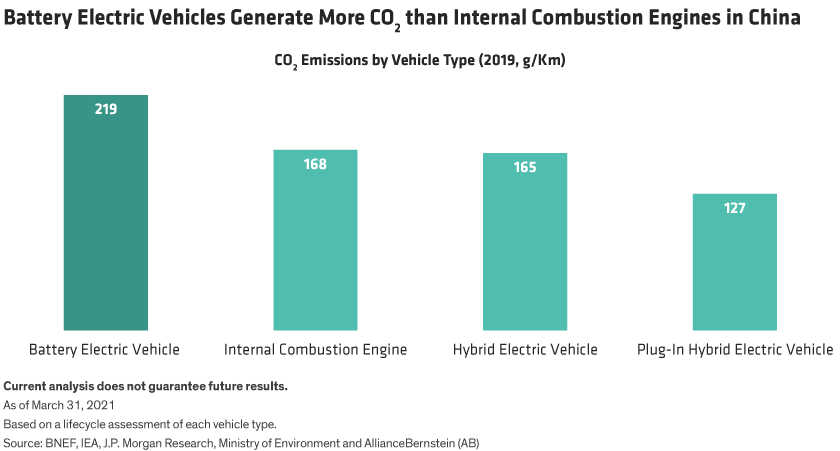

Building greener infrastructure overlaps with other policies like cleaner transportation adoption. China is the largest electric vehicle (EV) market in the world and aspires to have energy-efficient models account for a quarter of new automobiles by 2025. China also recognizes that powering an EV fleet with coal-produced electricity will only neutralize its own carbon cutting goals. Indeed, with the current infrastructure, battery-powered electric vehicles in China emit more CO2 than vehicles with traditional internal combustion engines (Display).

With an avalanche of new models coming to market over the next few years, EV adoption in China and globally is speeding up. As carmakers face intense competition and thinner profit margins, there are more attractive opportunities to be found in the EV supply chain, in our opinion.

Hydrogen will also become part of the green energy production mix over time. Hydrogen power is a potential solution for commercial transportation, as the current weight and energy density of lithium batteries are suboptimal. Many Chinese companies are already experimenting with hydrogen, with large state-owned enterprises rolling out hydrogen refueling stations.

The Focus on Global Commitment

China’s domestic agenda is being met with global collaboration. With the US re-entering the Paris Agreement, shared interests to address climate change create common ground for Washington and Beijing. After previous years of global unease, a multilateral approach to the planet will be welcomed around the world.

These are very early days for China’s multidecade carbon-neutral plan. But given the vast scope, it’s not too soon for investors to proactively monitor how the policies will be implemented—politically and across industries—in order to identify companies that will benefit from the most ambitious decarbonization program in the world.

Related: Understanding Your Bond Portfolio’s Carbon Footprint