Written by: Saskia Kort-Chick and Jeremy Taylor

Awareness that modern slavery is a social evil and investment risk continues to grow, putting investors in a pivotal position to identify and root out this risk across industries. Global mining is a particular challenge: risks to people in this industry are high and rising, and they’re not well-managed when compared with high-risk consumer-facing industries such as technology and apparel.

The mining industry sources its employees from particularly vulnerable populations, such as migrant workers and minorities. Many firms operate in geographies rife with conflict, corruption or weak judiciary systems. The work of mining itself is dangerous and the business models—which often rely on outsourcing and seasonal demand—can be high-risk, too.

It’s no surprise, then, that our research places the mining industry high among risks to people—both within its business operations and throughout its supply chains (Display). And in our view, the risks are rising.

Some of the rising risk stems from growing scrutiny from governments and intergovernmental organizations. The US has already implemented conflict minerals legislation, and the European Union (EU) implemented its Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive on January 5, 2023. The new directive will require large EU and non-EU companies with a significant presence there to report on social factors including working conditions, equality, non-discrimination, diversity and inclusion, human rights, and the effects of the specific undertaking on people and human health.

In February 2022, the EU Commission presented a Proposal for Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence. Once legislated, it will cover companies’ human rights and environmental obligations. In September 2022, it launched a Proposal for Forced Labour Regulation. The proposal doesn’t single out the mining industry, but it encompasses companies that use forced labor. If the proposal becomes law, it will ban their products from being imported by and exported from the EU.

The United Nations (UN) Sustainable Development Goals aim to eradicate modern slavery by 2030, and in December 2022, the UN-backed Principles for Responsible Investment launched an initiative to engage with companies on social issues and human rights. The largest effort of its kind, it was supported by more than 220 asset managers representing US$30 trillion under management.

The first targets for the initiative? The mining, metals and renewables sectors. Other sources of growing risks are geopolitical in nature. The push to make wider use of renewable energy sources along with other technological changes—including advances in military equipment—is driving intense demand for some minerals. Competition could be magnified even further, with not only companies but also governments battling for relatively scarce resources.

As these pressures increase, so will the uncertainty for people working in the mining industry, particularly those in the most remote and least transparent stretches of supply chains. And the stakes are raised for investors, as they seek to identify and manage risk to people in investment portfolios. How can these efforts be made more effective?

In Mining, Geography Is a Major Risk Factor

As we see it, the key is to have a strong framework for assessing modern slavery risk across all companies in the relevant investment universe, not just those that are in investors’ portfolios. Using a combination of fundamental analysis and specialist third-party research, it’s possible to prioritize companies and industries according to their modern-slavery risk exposures.

Our own framework is based on four key risk factors—vulnerable populations, high-risk geographies, high-risk products and services, and high-risk business models. All of these facets apply to mining operations and supply chains.

Why is mining risk so high? It’s an economically important industry, particularly to emerging countries. Of the 40 nations that depend on non-fuel minerals for more than 25% of their exports, 75% are low- and middle-income economies.

Because the industry is woven so deeply into emerging countries, it’s a key source of people risk in many of those areas. For example, artisanal and small-scale mining (referred to as ASM), a relatively dangerous occupation often plagued with poor safety practices, occurs mainly in these countries. According to the International Labour Office, nearly 13 million people work in ASM, and an estimated 100 million depend on it for their livelihoods.

People risks in many areas with mining operations include exploitative conditions in remote locations, the relocation—sometimes forced—of indigenous people to gain access to minerals, and association with organized crime or armed conflict. These dangers are likely to intensify, because much of the future demand growth for minerals will fall on high-risk geographies.

Engagement Yields Understanding…and Insights

While the broader modern-slavery risk framework is a useful tool, true insight comes from understanding each firm’s exposure. While the risk factors are high across the industry, they vary from company to company, as will awareness of risks and efforts to manage them.

Understanding individual modern-slavery risk exposures requires not only strong research skills and collaboration between fundamental analysts and in-house environmental, social and governance (ESG) experts, but also a clear sense of risk-management best practices.

A willingness to engage directly with firms to identify and address the issues is also key. Engagement for both insight and action has the potential to reduce risks not only for employees in businesses’ mining operations and supply chains, but also for companies and investors. It’s a golden opportunity to raise companies’ awareness of the modern-slavery risks they face and help them develop effective ways to manage them.

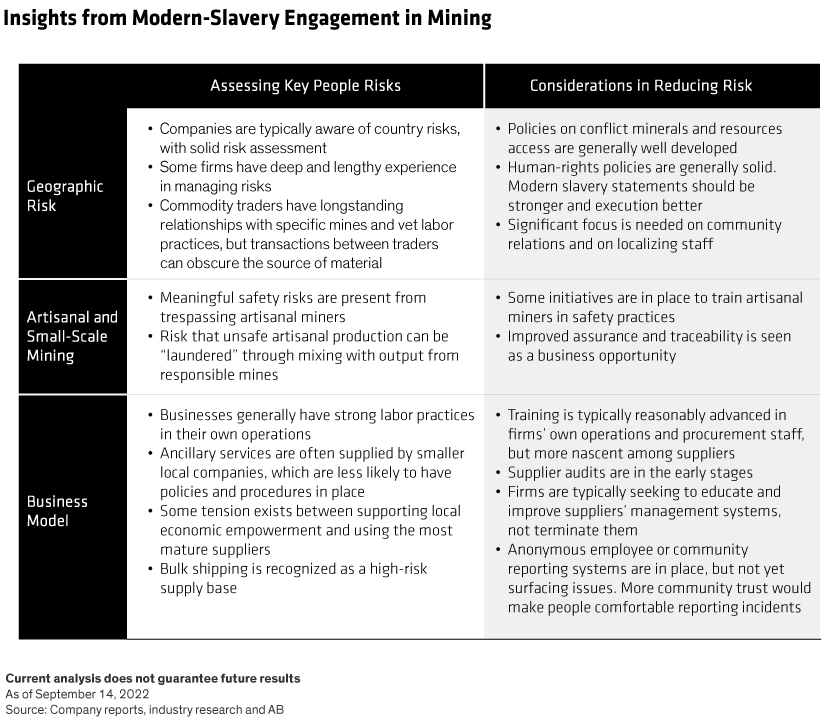

Our own engagement on this topic shows that, while risk awareness among mining companies is reasonably high or increasing, more action can be taken to manage the risks. For example, the companies we’ve engaged with generally have solid policies in place on human rights and modern slavery, but the quality of execution varies considerably. One key takeaway: training on this issue is quite advanced within firms’ own operations and procurement staffs but is still in the earlier stages with suppliers (Display).

In our view, companies have a long way to go when it comes to introducing modern-slavery risk audits into their supply chains. They’ve established anonymous employee or community reporting systems, but these mechanisms haven’t yet brought the issues to light, which raises important questions about their effectiveness.

How Investors Can Manage Their Risks—and Make a Difference

Based on our assessment, the global mining industry is high risk in nature, and it lags other industries, such as technology and apparel, in risk awareness and reduction efforts.

Part of the challenge stems from these industries’ different structures. Technology and apparel are highly sensitive to consumer opinion, and modern-slavery awareness is rising among all-important consumers. Because mining companies do business mainly with other companies, they’re to some degree more insulated from consumer opinion than their retail peers.

But that insularity won’t last.

The industry’s corporate customers are becoming more aware of modern-slavery risk and applying more stringent requirements to the miners that supply them. Governments are stepping up their scrutiny of mining companies and supply chains. In the short term, this poses a challenge to mining operations and revenues, and it puts more pressure on investors to diagnose which businesses are responding effectively to the increased attention.

With a thoughtful framework, sound research and company engagement, investors can identify and manage these risks in their portfolios. At the same, they can help mining companies improve their people risk practices—and ultimately make life safer for many of the industry’s millions of workers.

Related: Portfolio Implications of a Post-Peak Inflation Climate