A provocative report by Credit Suisse’s Zoltan Pozsar that was making the rounds in certain corners of Twitter last week suggests that the Russia-Ukraine conflict could be a strong tailwind for shipping freight rates.

The report features a lot of big thoughts, shipping rates being just one of them, so I’ll try to keep things as simple as possible.

According to Pozsar, Credit Suisse’s head of short-term rate strategy, the global commodities market is facing a crisis due to the conflict in Eastern Europe and the international sanctions that have been piled onto Russia, one of the world’s biggest suppliers of everything from natural gas to nickel to wheat. The price of commodities traded outside of Russia are now surging on a sanctions-triggered supply shock; meanwhile, those traded inside Russia have stalled in many cases, and crashed in others, since many of these materials have effectively been unplugged from the rest of the world economy.

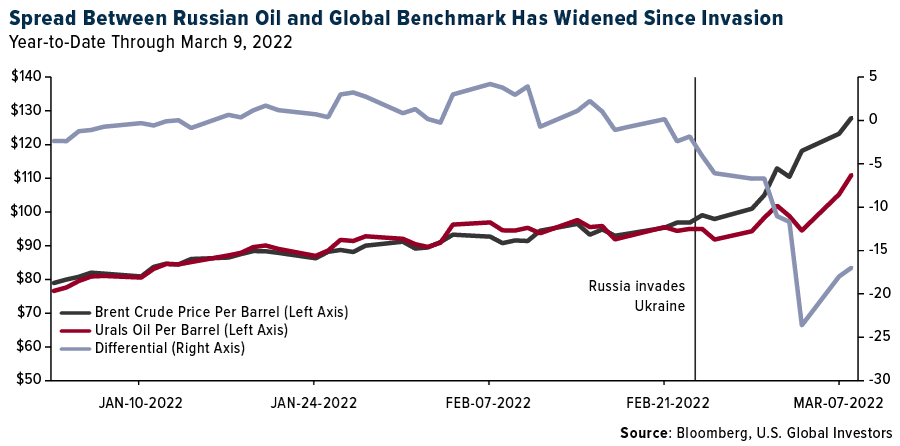

Here’s one such example. Historically, the spread between a barrel of Brent crude oil (the global benchmark) and Russian Urals crude has been very tight, often differing no more than a couple of dollars per day. Ever since Russia invaded Ukraine, however, the spread has widened as Brent has skyrocketed much more dramatically than the price of Urals.

As Pozsar points out, a buyer must come in to support cratering prices and close the spread between Russian and non-Russian commodities. The problem, though, is that Western nations are unable to do so since it’s their very own sanctions that have created this crisis. Despite attractive prices, as much as 70% of Russian oil lacks buyers at the moment, according to Lloyd’s List.

So then who’s the buyer? Pozsar believes the most likely answer is the People’s Bank of China (PBoC), which has vowed to continue normal trade relations with Russia and may be interested in gobbling up cheap Russian commodities to support its currency, the yuan. (Remember, China, like Russia, has gradually been shifting away from the U.S. dollar as a reserve currency.)

What does this have to do with shipping rates? China may not have enough storage capacity on land for all the Russian commodities bought at a deep discount, and this could force the country to store them on floating vessels. As Pozsar writes, “the price the PBoC will be paying to lease ships to fill them up with Russian commodities can in theory rise as much as the collapse in the price of Russia commodities: a lot.”

Spot Earnings Are Already Spiking

Now you may think there are too many “ifs” and “maybes” in Pozsar’s thesis, but actual events appear to be playing out as described.

For one, Bloomberg reports that China is already considering buying big stakes in distressed Russian energy and commodity companies, including oil producer Gazprom and aluminum producer United Company RUSAL. The two countries have been strengthening ties, “with President Xi Jinping and Vladmir Putin last month signing a series of deals to boost Russian supply of gas and oil, as well as wheat,” the article reads.

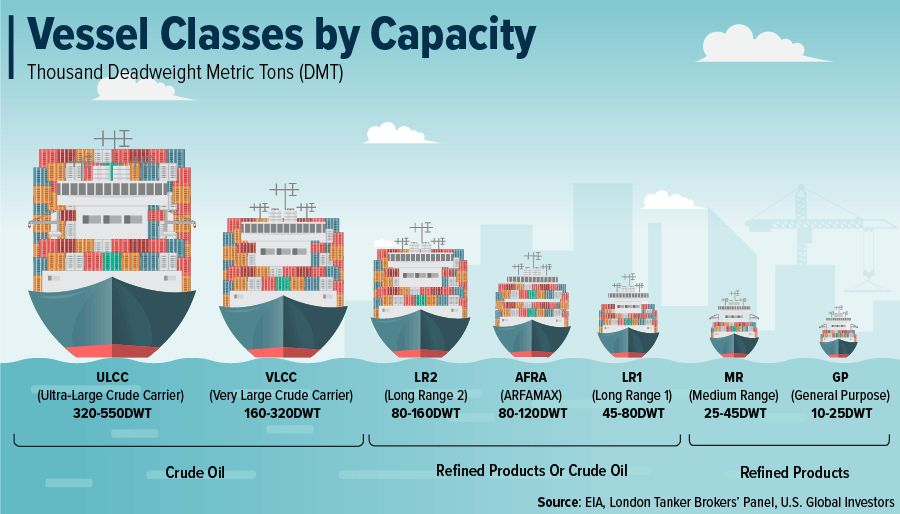

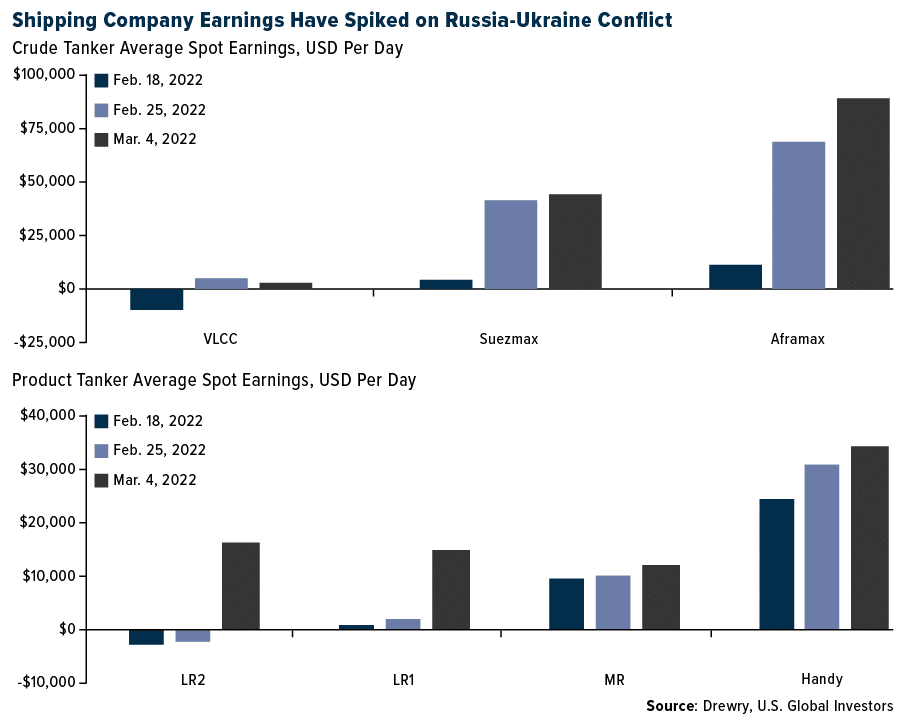

In addition, daily average earnings for crude tankers and “product” tankers, which carry gasoline and other refined petroleum products, have surged since Russia’s invasion. In a report dated March 9, Drewry analysts Nikesh Shukla and Santosh Gupta write that spot earnings have increased due to a vessel shortage as traders rushed to lock in carriers and some operators were unwilling to sail into the Black Sea region. Earnings for smaller-class vessels—which, unlike very large crude carriers (VLCCs), can access canals and ports of all sizes—have seen among the biggest jumps from February 18, before the invasion, to March 4.

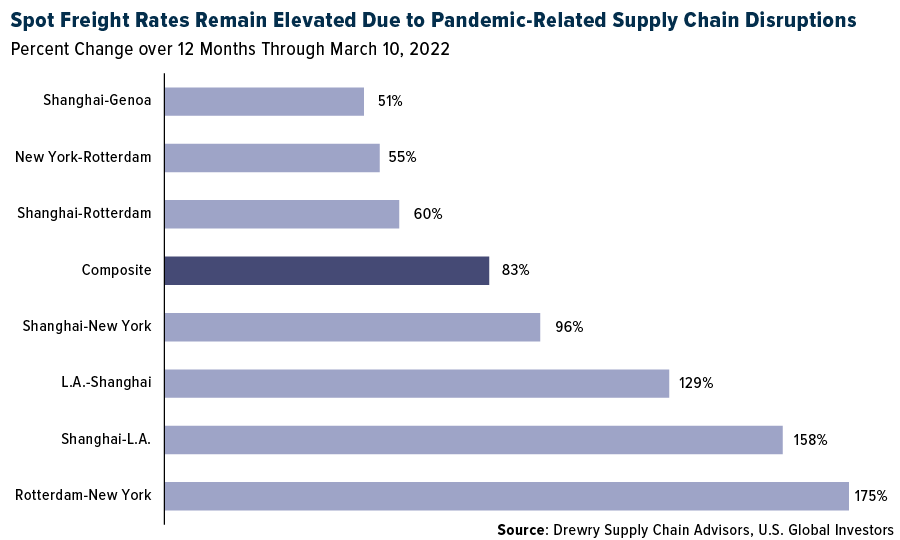

Remember, shipping freight rates are already highly elevated due to the pandemic-related supply chain imbalances. Spot prices are up 83% on average from the same week last year, according to Drewry. To ship a container from Shanghai to Los Angeles costs exporters 158% more than it did a year ago; the Rotterdam-New York route is as much as 175% more expensive.

Investors have taken notice. Compared to the broader market, which has fallen into correction or even bear territory since the start of the conflict, shares of many shipping and logistics companies have popped. Among the biggest movers between February 24 and March 10 are Japanese carriers including Mitsui O.S.K. Lines (up 26.7%), Kawasaki Kisen Kaisha (up 20.9%) and Nippon Yusen Kabushiki Kaisha (up 20.0%). Taiwan’s Evergreen Marine (up 10.3%) and Yang Ming Marine Transport (up 10.2%) have also jumped.

Bitcoin Could Also Benefit

The other point I’d like to highlight from Pozsar’s report is that the conflict could bring about the end of the global monetary system that’s been in place since 1971, when President Nixon ended commodity-based money. This system “crumbled,” Pozsar asserts, “when the G7 seized Russia’s FX reserves.”

He’s referring, of course, to wealthy countries’ decision to freeze all assets belonging to the Central Bank of the Russian Federation, a move historically reserved for true pariah states such as North Korea, Iran and Venezuela.

At the other end of this crisis, the Chinese yuan’s value could be a lot higher (thanks to the discounted Russian commodities) and the dollar’s value a lot lower.

As a result, “Bitcoin… will probably benefit from all this,” Pozsar writes.

I agree. Unlike fiat currency, Bitcoin is private property. No person or government entity can “freeze” it. Many investors, regardless of how they feel about this geopolitical conflict, see the severity of the economic sanctions against Russia and conclude that Bitcoin is an escape hatch from the monetary system that makes such seizures possible.

Related: Russia Is The Target Of The Harshest Sanctions On Record. Will They Be Enough?